Michael Ray Charles with Mara Hoberman

Interview

Mara Hoberman in conversation with Michael Ray Charles as the artist is preparing his first solo show in NYC in more than 20 years: ‘Veni Vidi’ at Templon.

Mara Hoberman – Let me start by asking you about the title of the show, “Veni, Vidi.” Usually there’s a third word there, but you’ve left it out. Why?

Michael Ray Charles – “I came, I saw.” That’s it. The “I conquered” part…that’s another story. My objective is not to conquer. For me, “I came, I saw” relates to the way I have been able to cultivate a visual language and use this visual language to articulate something about the world; about what I’ve seen and what I see.

MH – Victor Hugo wrote a poem about his daughter titled “Veni, Vidi, Vexi,”[1] which translates as: “I came, I saw, I lived.” Perhaps the title of your show is somewhat in keeping with that context of family and how family fits into a larger sense of history.

MRC – Yes, I often think back about a time when my son was in middle school and really into sports. My wife was doing fundraising for the team and wanted to buy trophies to give out to the students. Well, there we were in the shop looking at all the trophies and just not seeing our son or his schoolmates reflected anywhere. The faces on the trophies were all generalized, of course, but they also clearly referenced white people. None had anything to do with the students on my son’s sports team who are black, Indian and Vietnamese. It is very hard—and very telling—that, even when our kids are gifted and superior, if we want to acknowledge this, the only option is a trophy that looks nothing like them. I’ve come to realize that even in moments of triumph, minorities are faced with defeat in many ways because the symbols of accomplishment and excellence don’t look like them.

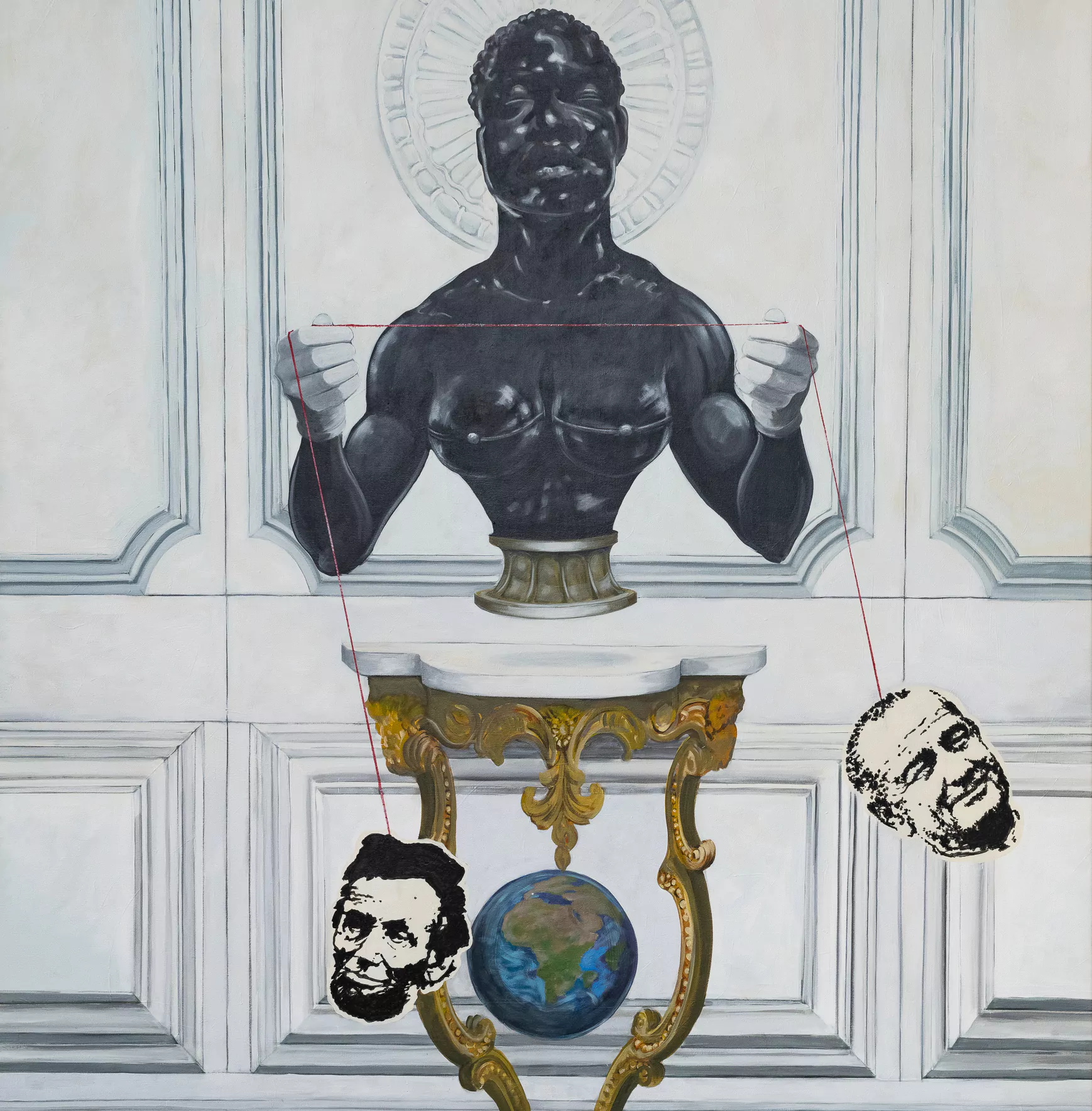

MH – There’s also a painting in the show that shares the title of the exhibition, (Forever Free), Veni, Vidi. In this painting we see the heads of two American presidents (Abraham Lincoln and Lyndon B. Johnson) attached to either end of a red string that is being held up by an androgynous bustier-clad black portrait bust. The historic figures are American, but the setting feels very European because of certain architectural details (like the ornate wall moldings) and furniture (the side table with gilded legs). Is the contrast between cultures and time periods intentional?

MRC – It’s very intentional. I am acutely aware of how architecture and interior design create a cultural context. The architectural design elements that you’re picking up on, like the crown moldings or the wainscoting, are still popular today, but they also harken back to a certain historical period that evokes pure pleasure for some and pure pain for others. So this painting, and others like it, is my way of bringing the past forward and providing an historical context. In this and other paintings in the exhibition you will find references to Versailles and also to adornments typically found in European cathedrals dating back to the 1600s. It’s important also that the architectural context is always a shallow one, I mean in terms of representing space. I’m still quite interested in the idea of life as a performance and so the settings of my paintings are always very theatrical, stage-like.

It’s very intentional.

I am acutely aware of HOW architecture and

interior design create a cultural CONTEXT.

MH – And as for the paper heads of the two American presidents, it appears as if they are being weighed against each other. They are hanging there on either end of that piece of red string, but it seems ambiguous as to whether they are being measured based on their virtues or, perhaps, for their misgivings.

MRC – I think that the important decisions that these two leaders ultimately made, regardless of whether they were totally for emancipation (in the case of Lincoln) and civil rights (in the case of Johnson), are like brackets framing the black experience in America. During COVID and, what I will call “the reckoning” that took place shortly after George Floyd’s death [on May 25, 2020], there was a lot of emphasis on the Civil War. Americans still can’t seem to get on the same page about what that war was really about. Looking around and seeing what was happening politically in the wake of George Floyd’s death, I felt like we were moving backwards in terms of laws that were being passed, the type of language that was being utilized, and a general evasion of—or just complete disregard for—the truth. So many of the things that I think that allowed American society to come together in the 60s and which paved the way for a more tolerant times in the 70s, 80s, and 90s were being removed. All of the trust that had been gained was suddenly lost. When I think about all of this, the symbol of a pendulum swinging back and forth between contemplations of Africans is an important reference.

MH – Were most of the paintings in “Veni, Vidi” made in the wake of George Floyd’s death, or were you working on some of them for much longer?

MRC – Interestingly enough, I got very little done in terms of making art during the pandemic. So this show includes works made mostly in the last few years. Some paintings are fresh of the boat, made just this last fall.

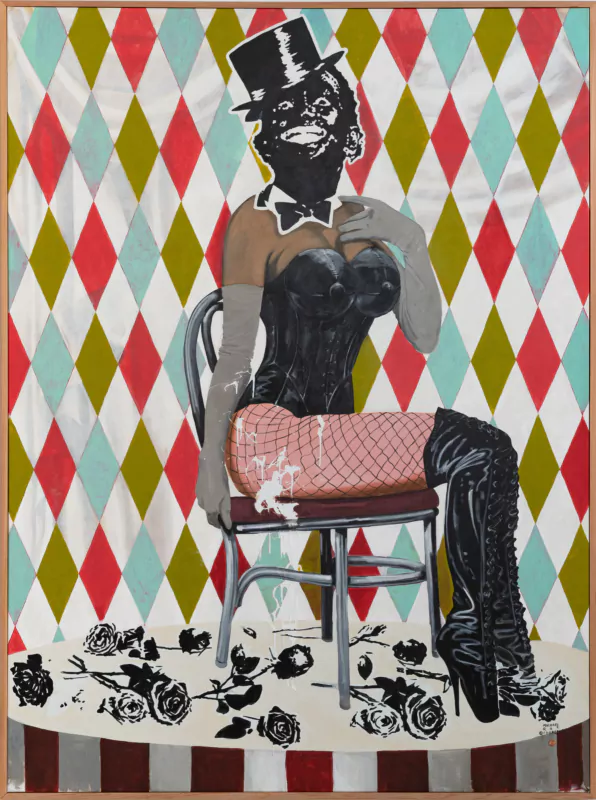

(Forever Free) A One ‘Man’ Show, 2022. Acrylic latex and copper penny on canvas, 94 1/2 x 69 7/8 in. (240 x 177, 5 cm)

MH – And are some of the paintings we see in “Veni, Vidi” older works that you’ve recently reworked? Can you explain that part of your process?

MRC – I do rework paintings that stay in the studio. In some cases, paintings will change radically and become something totally different. Sometimes an idea comes across in one iteration but then, with more thought, it might drastically change overnight. Many of the paintings convey the same ideas just with a different execution. I typically work on several paintings at once. Right now there are five paintings in my studio, but I’ve had as many as twelve in there at the same time. I’m always engaged with multiple paintings at the same time, because I’m constantly comparing and contrasting.

MH – It’s been a while, over twenty years, since you exhibited in New York, but you just had a major show in Paris last year. Do you think that your work reads—or is received—differently in Europe and in the United States? Are you thinking about different audiences and contexts when you paint?

MRC – A long time ago, I came to understand that all an artist needs is an opportunity for his or her work to be seen. I try to create work that has the ability to communicate to anyone and everyone who is capable of standing in front of the painting and who is willing walk down the road with it, so to speak. But I’m also conscious of the fact that all cultures have their own very specific collective consciousness and that this context necessarily shapes how people see things and interpret them. Every culture has a shared language, which includes music, visual forms, body language, hand gestures, etc. All of these things influence how someone might understand a painting. Yes, things are different in the US and in Europe, but I’ve also noticed an intensified globalization in the past 15–20 years. In many ways the world is getting smaller. I’m thankful to have an opportunity to exhibit my work and I don’t expect that everyone will respond the same way or get everything that I’m trying to say. But that is not my objective.

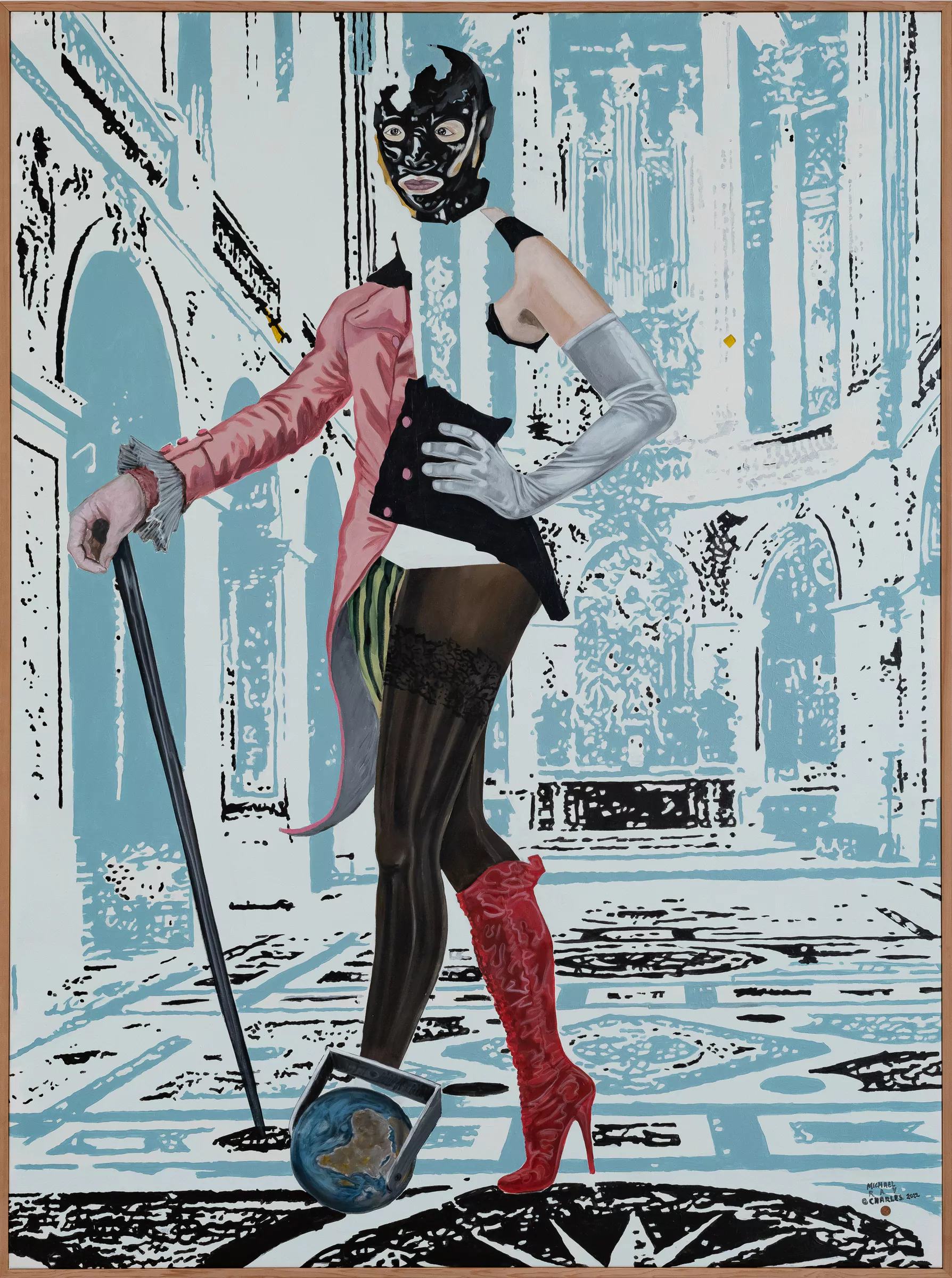

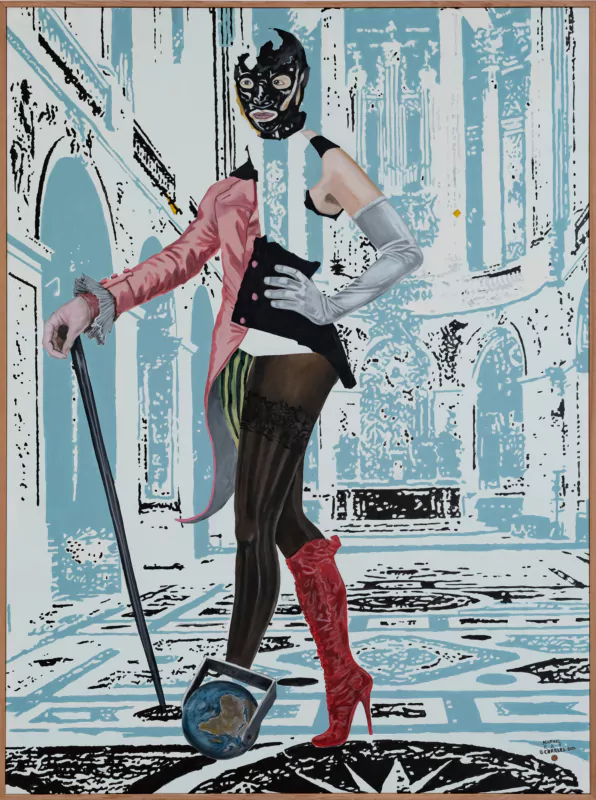

(Forever Free) My Long Tail Butterfly, 2022. Acrylic latex and copper penny on canvas, 94 1/2 x 69 7/8 in. (240 x 177, 5 cm)

MH – I notice some new themes emerging in your recent works, specifically around sexuality and gender identity. What inspired you to start tackling these issues?

MRC – Those are important issues today; there’s a lot of uncertainty surrounding the LBGTQ communities. Bringing in these themes is also as an extension of my attempt to understand the impact and the effects of minstrelsy, the 19th century minstrel shows. One component of these shows was cross-dressing. For years I was making images that only referenced black males, and this bothered me. So I came up with an image that I thought could represent both male and female. There are a lot of aspects of minstrelsy that I address with my work including, masquerade, burlesque, desire, carnival and, of course, power dynamics. My work now is different in many ways than the work I made 20 years ago; I’m going deeper.

MH – I know that your practice involves a lot of in-depth research. What have you been digging into recently?

MRC – I’m always reading. For a while I was stuck on trying to figure out the images of blacks that appear in antiquity. I was reading Frank Snowden’s book: Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience. It’s not true that there was no racism in ancient Rome. Racism is a byproduct of ignorance coupled with power. And if you look at some of these early representations of blacks, I think you’ll see that that those images can be linked to 19th century stereotypes. I can’t say it enough, in my work, and in general: the past is present.

—

Michael Ray Charles, ‘Veni Vidi’, Templon New York, until May 6, 2023

Mara Hoberman is a Paris-based art historian and critic. She is a regular contributor to Artforum and is currently conducting research for the Joan Mitchell catalogue raisonné.

[1] Published in 1856 as part of “Les Contemplations” (The Contemplations)