Jim Dine, as words go

Essay

Returning from the Venice Biennale, art critic and curator Philippe Dagen meets Jim Dine in his studio in Montrouge, in the Paris region.

Jim Dine, as words go

By Philippe Dagen

The first thing you notice when you enter Jim Dine’s studio is the words. They are everywhere in this former garage in Montrouge. Sheets of paper are nailed to boards placed in the corners, long vertical strips on which words follow along in short lines, in handwritten capital or tiny letters. Other sheets are pinned to the wall like posters. Just now, Dine covers a fragment of a sentence with grey paint, taking advantage of the fact that the visitor is wandering between the partitions, the accumulated works and the shelves loaded with books, pots of powdered colours, various bottles and a whole range of batteries for saws and drills.

Questioned about the abundance of these inscriptions in the studio, he shoots back: “It’s reassuring to see the words.” These come to him suddenly, or he finds them around him. “It’s a unique moment: that’s it, here I am. It’s the same with objects: I find them and include them.” They are there, right in front of him, ready to be used. “I walk around the studio, I change, I move, I tear, I glue, I let things come.” His thoughts and gestures can thus move freely from poetry to painting or sculpture. His three modes of creation come together and support each other. His studio is a kind of total work of art. “Yes, that’s all I want. I’ve lost all interest in social life, it’s ridiculous. The studio is the only place I want to be.” And so he has several of them, moving between his spaces in Montrouge, Göttingen, St. Gallen, and Walla Walla in Washington State. He likes to travel from one place to another, he admits, because he always leaves “with the idea that something is going to happen.” He makes sure to have a notebook in his pocket. “Or, on planes, I use vomit bags because the paper quality is so good,” he says with his characteristic sense of humour.

Back to these poems: they are often very enigmatic. One of them begins: “Free of enchantment, The white bowl, Eats the blossoms, A special red fruit, free milk and the comfort of childhood.” And another: “Now the doctor comes to dance, The train arrives, Rosie takes me home, and I go….” Dine is happy to explain this. It’s totally autobiographical. The train is a childhood memory. In Cincinnati (Ohio), where he was born in 1935, his family lived near a small station, and his father used to take him there to watch the trains go by. “You could still see the railwaymen throwing the coal into the boiler. They were huge machines, those trains. They fascinated me.” In a previous conversation, he had already mentioned the history of his family of Jewish emigrants from Poland and Lithuania. They first settled in Georgia, a state in the south of the United States. They left for Ohio because of the anti-Semitism of the Ku Klux Klan. He alludes briefly to “the racist history of the United States” but prefers to speak of his teenage years and, more particularly, the house of his grandfather, a plumber; and the hardware store where he plied his trade.

“When I was eight years old, I was in charge of cutting the tubes. It was a very fine machine; you had to place the tube and fold the cutter back to the exact spot. To lubricate the mechanism, there was oil, lots of black oil, and the floor was covered in it. The swarf would fall and get stuck in the oil. It was very beautiful.”

“That’s when you became a painter?”

“Yes, you could say that. In fact, all the things in my grandfather’s store – the tubes, the instruments, the materials – gave me a lexicon that I still use today.”

“His thoughts and gestures can thus move freely from poetry to painting or sculpture. His three modes of creation come together and support each other. His studio is a kind of total work of art.”

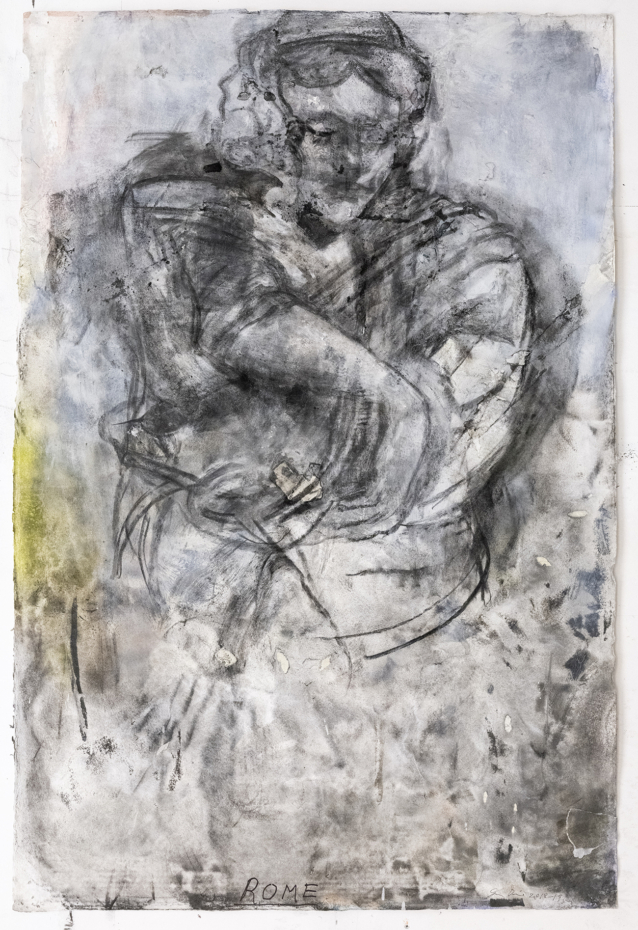

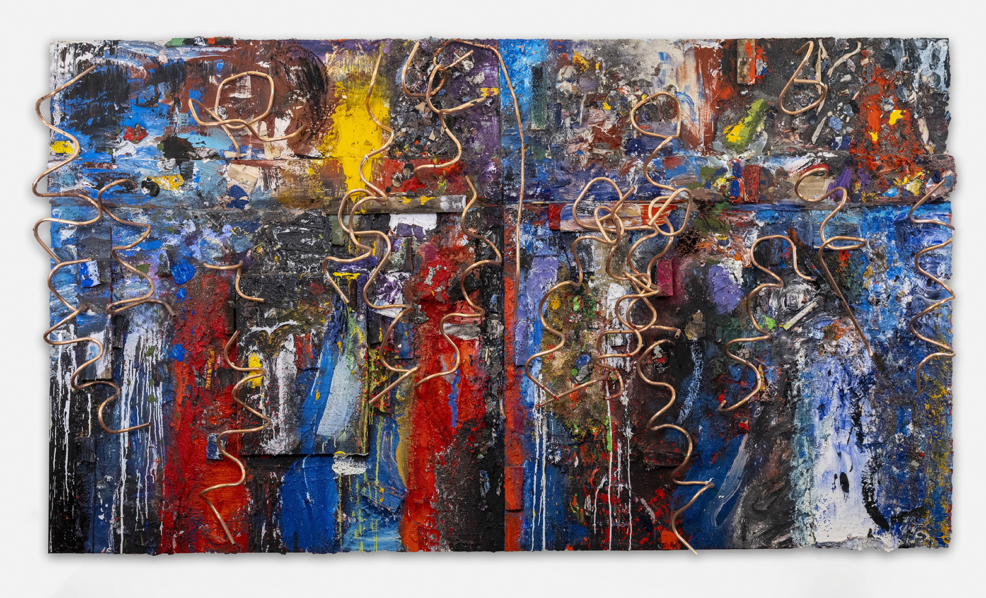

To realise this, I need only take a few steps. Behind one of the partitions that have been erected between the pillars is the space reserved for painting. The eye immediately settles on a work in progress: a long, tall slab of wood is splattered with drips and stains, from intense blues to pale yellows, oranges and reds. The black and white grid of a checkerboard is painted on it. Small pieces of painted wood are glued on. But what you see first are the grey steel tubes fixed in front of the paint, zigzagging in the air. A metal and wicker armchair is caught by its back. The work was started after his return from the Venice show. “To avoid getting depressed, I had to start something. And so I did. But I don’t know how the story will play out.”

The Waltz (Grunewald)

When I pointed out to him that, usually, the tubes he likes to place in front of his compositions are made of copper and draw curves, whereas this time they are made of steel and form right angles, he explains again: “They are the same tubes that I would cut up when I was a child. They hardly use them any more. In fact, we had a lot of trouble finding them, we had to go to three different suppliers to get what I needed. Today, all you can find are these horrible plastic pipes.” It seems that their main flaw, in Dine’s eyes, is that they are totally unsuited to artistic uses. But nostalgia also plays a part in his disgust, which he admits, while laughing at himself.

Contrary to what you might think, the checkerboard is not a tribute to Duchamp and the game of chess. “I don’t play chess, I play draughts,” says Dine. But he is happy to talk about Duchamp and his wife Teeny, whom he met in New York in the 1960s: “They were very nice to me, as they were to Rauschenberg, Johns, Cage and the others. They came to all the shows. I didn’t get to know him very well: I thought of him as an extremely dignified old man. But I knew Teeny a little.” Thus begins one of those meandering autobiographical stories at which he excels. We learn that Teeny Duchamp, who was originally the wife of the gallery owner Pierre Matisse, son of Henri, was, like Dine, a native of Cincinnati. She was the daughter of a well-known and wealthy surgeon, Robert Sattler – “very high society, big money,” as Dine puts it. She had a classmate at school named Clarence Lubin, who became a renowned mathematician and was involved in the Manhattan Project. Clarence Lubin was Dine’s cousin. “He was even the only one,” he recalls, “who understood me and helped me when I was starting out, at a time when my whole family disapproved of my desire to become an artist. So Teeny could pretty much see who I was.”

A few steps away from this large painting in progress, on an easel, a drawing is pinned to a board: a portrait of a man, probably in his sixties, still unfinished, extremely realistic, a far cry from Dine’s best-known style. It’s an old Californian friend of the artist’s who comes to see him from time to time. He posed three times, and will be back. “I love these sessions. I talk to the model all the time, I ask questions, I get to know him better.”

“It all starts with drawing. Not because I draw sketches before painting or anything like that: not at all. But drawing teaches you to look carefully and to trust what you draw on the paper. There have even been times when I’ve stopped working for a long time and just drawn. That’s how I’ve been able to educate my eye and learn to make certain visual decisions when I’m working. I’m sure of it: drawing has given me everything.”

The conversation turns more serious again when I point out to him how different the style of this portrait is from that of other drawings of his, including his self-portraits, and even more so from his way of painting. “I don’t know,” he replies at first. And then: “It’s not conscious. I just do what’s appropriate. I don’t choose, it’s just necessary. It’s a question of skill, nothing more.” But how does he explain this skill? “You’re born with it. Then you hone it by looking, by working.” And, continuing: “It all starts with drawing. Not because I draw sketches before painting or anything like that: not at all. But drawing teaches you to look carefully and to trust what you draw on the paper. There have even been times when I’ve stopped working for a long time and just drawn. That’s how I’ve been able to educate my eye and learn to make certain visual decisions when I’m working. I’m sure of it: drawing has given me everything.”

—

Header: Exhibition view, Dog on the Forge, 60th biennale di Venizia, Palazzo di Rocca, 2024.

2nd image: Philippe Dagen and Jim Dine at the artist studio in Montrouge, Paris, 2024.

Last image: Exhibition view, Dog on the Forge, 60th biennale di Venizia, Palazzo di Rocca, 2024. Photo © Ugo Carmeni

Philippe Dagen is a professor of contemporary art history at the University of Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, an exhibition curator, and a critic for the daily newspaper Le Monde. His research centres on “primitivism” in the twentieth century, on the relationship between creation and war, and on current art.

Né en 1935 à Cincinnati dans l’Ohio, Jim Dine vit et travaille entre Paris, Göttingen en Allemagne et Walla Walla aux États-Unis. Pionnier du happening et compagnon du Pop Art, il emprunte une voie singulière. Grand expérimentateur de techniques, il travaille le bois, la lithographie, la photographie, le métal, la pierre ou la peinture. L’outil et le processus de création sont aussi cruciaux que l’œuvre achevée. L’artiste explore les thèmes du soi, du corps, de la mémoire à travers une iconographie personnelle composée de cœurs, de veines, de crânes, de Pinocchio et d’outils.