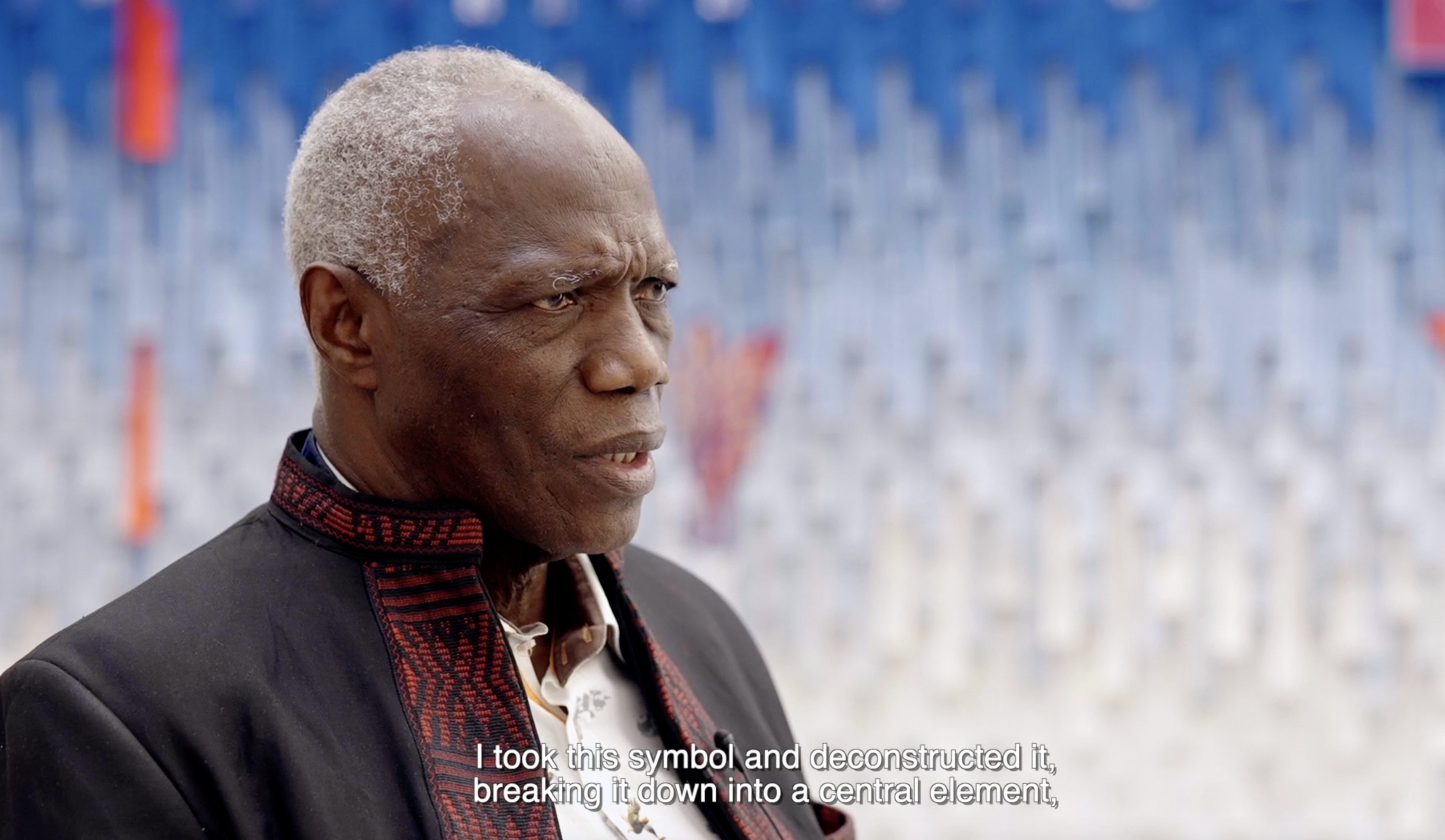

Abdoulaye Konaté

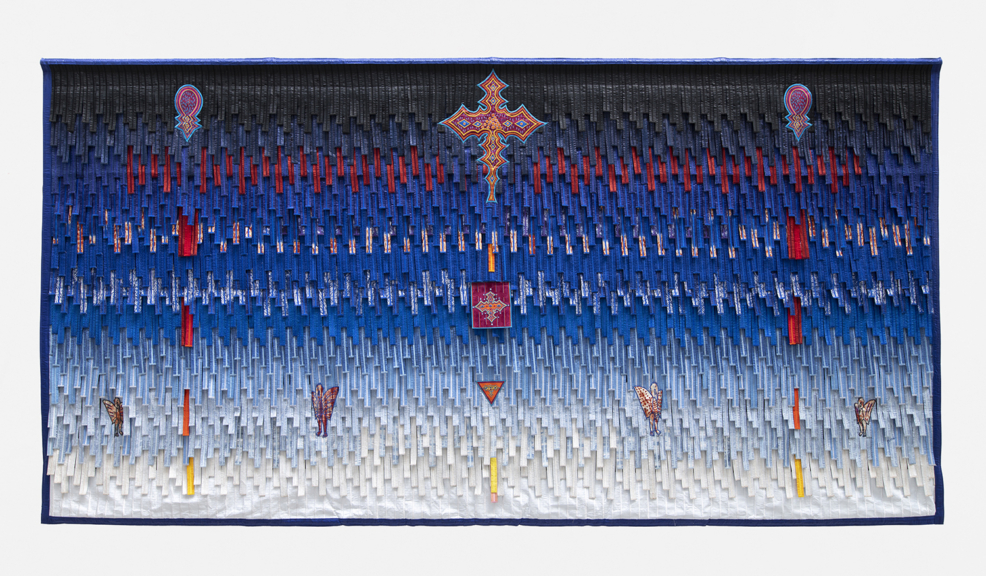

The Soul of Signs

Malian artist Abdoulaye Konaté is exhibiting his work for the very first time at Galerie Templon. The gallery’s Brussels space is hosting the The Soul of Signs exhibition, a brand new series of seven textile pieces.

Abdoulaye Konaté, known as the Master, was born in 1953 in Diré, Mali. He is a leading figure on the African contemporary art scene. In the 1990s, he swapped canvas and brushes for needle and thread as fabric developed into his favourite medium. His work combines Western modernism with African symbolism, addressing social and political issues such as religious fanaticism and social justice with a complex and shimmering palette that has become his signature over the years.

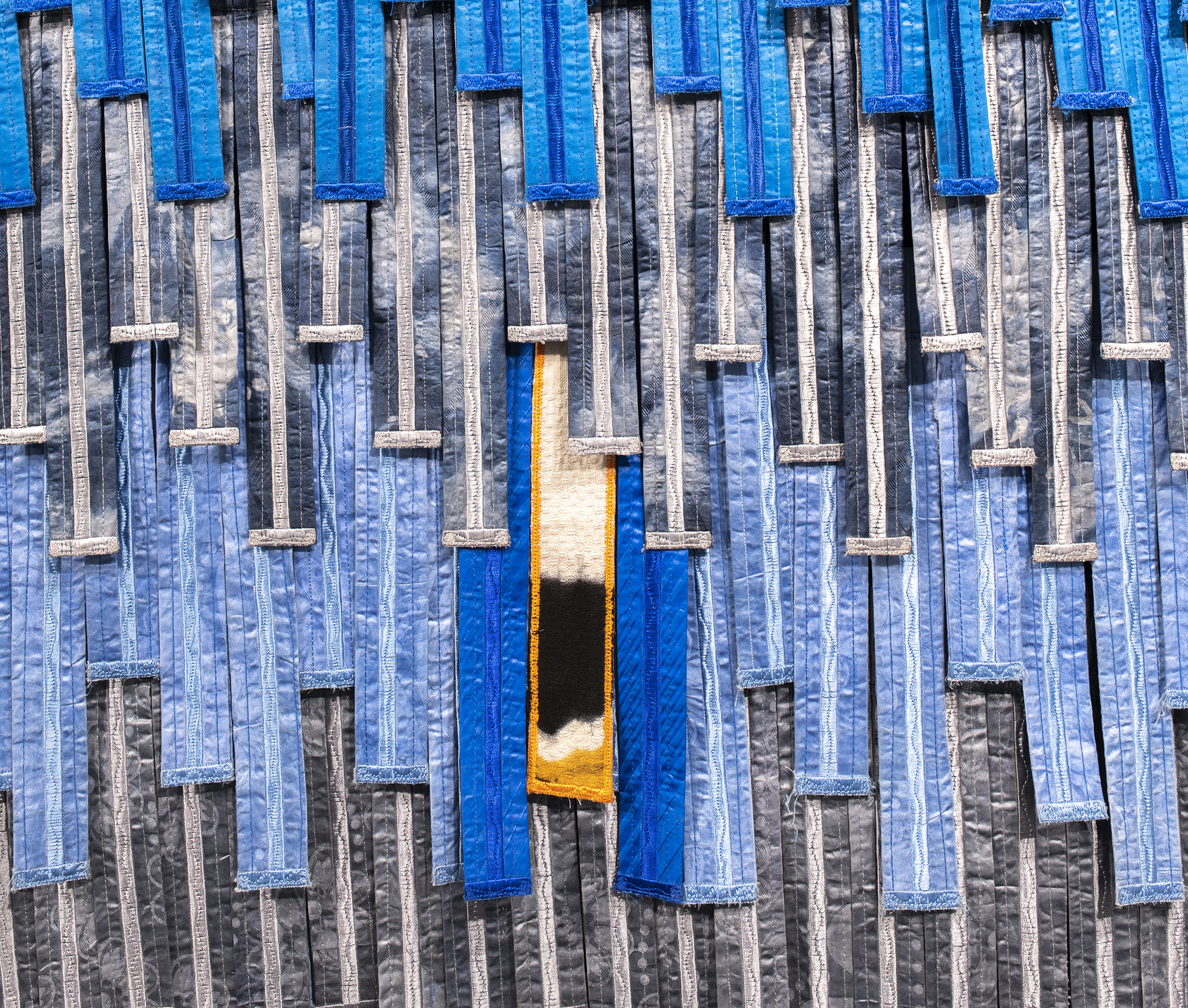

The Soul of Signs exhibition covers the gallery walls in majestic hand-embroidered canvases. The artist creates them using offcuts of African Bazin fabric which he dyes then rearranges in entrancing shaded tones, from fiery red to midnight blue, emerald green to golden yellow. “Nature is an endless source of colour inspiration to me,” explains the artist. “A butterfly, a bird, a chameleon or a starry sky inspire me every day to come up with new pigments.”

Konaté uses fine thread to embroider mysterious linguistic symbols on his multi-hued canvases. He finds the symbols during his travels, on the rim of 16th-century Tunisian ceramics, for instance, or at the heart of Berber art museums. “These marks have their own soul because they bear within them the heritage of a culture,” explains the artist. “Today’s generations have a duty to ensure that not everything is forgotten, to make use of these keys to our past and adapt them to contemporary society.”

Motif du Mandé et Calao Sénoufo

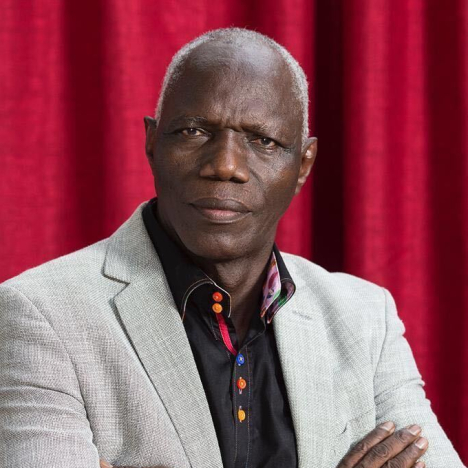

The artist

Abdoulaye Konaté, born in Diré in 1953, is one of Africa's leading figures in the visual arts. He works in tapestry, dressmaking, painting and sculpture, using fabric as his main creative material. He creates installations in which he uses traditional objects as an alphabet. By combining Western modernism with African symbolism, he fuses the expressiveness of traditional textiles with symmetrical, even hierarchical compositions, evoking the protection of ethnic and cultural heritage, Africa's place in the world, and global socio-political relations that resonate far beyond his local context.