History

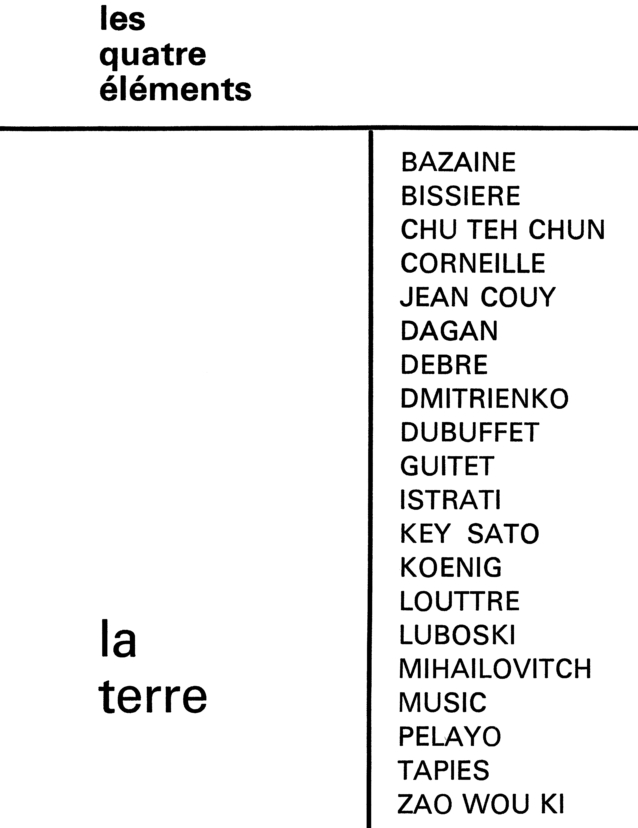

The four elements

Earth

February 16 – March 18, 1967

Of all materials, earth is the first. The earth takes on infinite aspects and meanings in the human mind. Every landscape can be seen as an ode to the earth, which nourishes plants and flowers, rises into hills, bristles with mountains and is carved into valleys by the waters. The modern painter gives the earth an autonomous existence. What was new in the mid-twentieth century was the way in which artists approached the earth in its most concrete aspect, in a way that could be described as materialistic. It’s the earth itself, raw, oily or arid, the earth we walk on, that is the very subject of these works. Through this dialectic, the painter achieves a new, revealing poetry that prompts us to proclaim: yes, all land is promised, all land is holy.

Georges Boudaille, Extract from the text of the invitation, February 1967

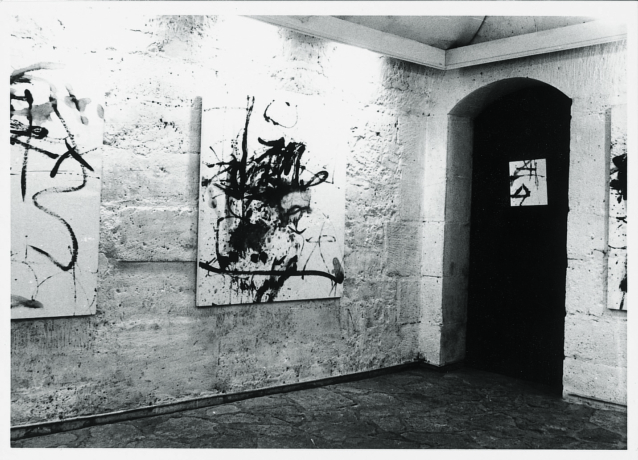

Djoka Ivackovic

April 20 – May 16, 1967

In this ill-defined time, when everything shrinks and collapses, when the painter invents and then recapitulates as he goes along, when consciousness straddles the line between total oblivion and the intoxication of a possession ready to be exorcised, in this time of gesture, before the gesture becomes the tangible conclusion of an inner mirage, for Djoka Ivackovic, I feel that this is where we should start talking. There is no shortage of epithets for a painting that is unrepentant because it is “gestural”. Irredeemable, definitive…

But what’s astonishing about Ivackovic’s work is that, through the confusion of its cursive inscriptions, each lead never ceases to have that unique, essential character, capable of shrinking the pictorial space within it. Whether the spray dissolves in a final spiral, or bursts because it has fallen too far onto the canvas surface, everything comes back to the absolute stripping away of the sign in its power of appropriation.

Jean-Loup Majewski, Les Lettres françaises, April 1967

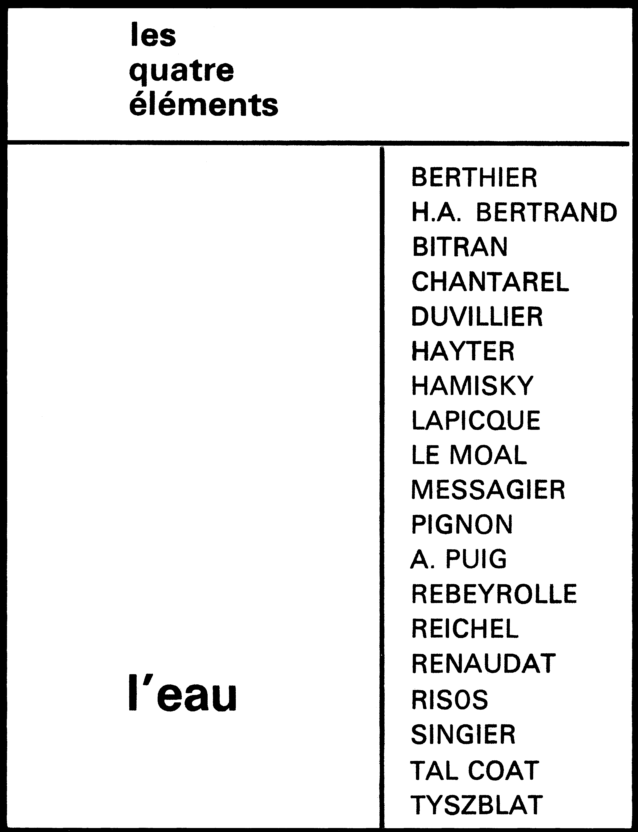

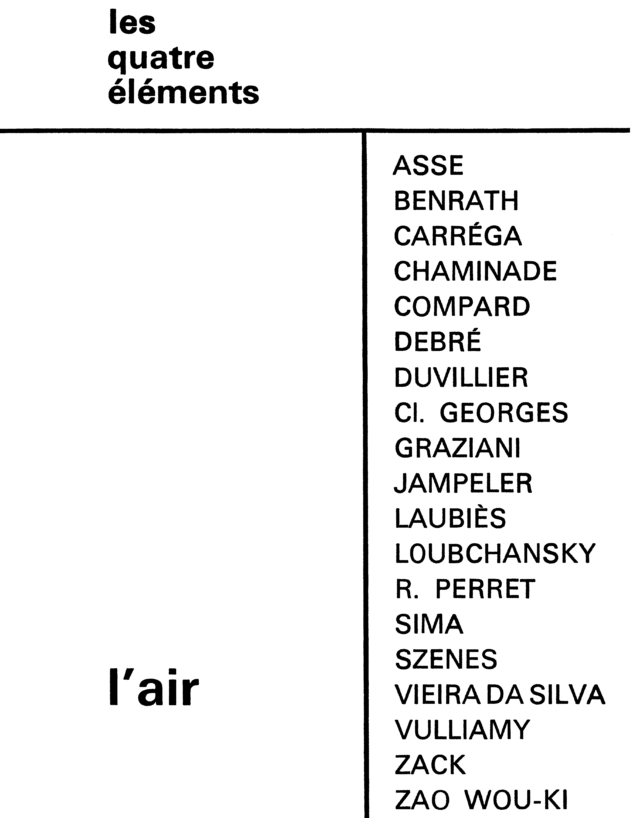

The four elements

Water

June 8 – July 8, 1967

Le japonais Ado est peut-être la plus moderne des peintres orientaux de Paris. Sa vision est décantée à l’extrême. Il n’en demeure qu’une line, pure, stylisée, tendre et de légers effets de surface. Au-delà de l’objet, il faut savoir découvrir la personnalité de l’artiste, sa volonté de capter l’essentiel, une intransigeance mais aussi une vibration qui trahit son émotion et son angoisse. Pour s’exprimer d’une manière plus journalistique, je dirai que la peinture de Ado se situe dix ans après la fin du Op’art. Elle se projette dans l’avenir, avec une allure futuriste qui rejoint les audaces de nos couturiers d’avant-garde.

Georges Boudaille, Les lettres françaises, 20 octobre 1966

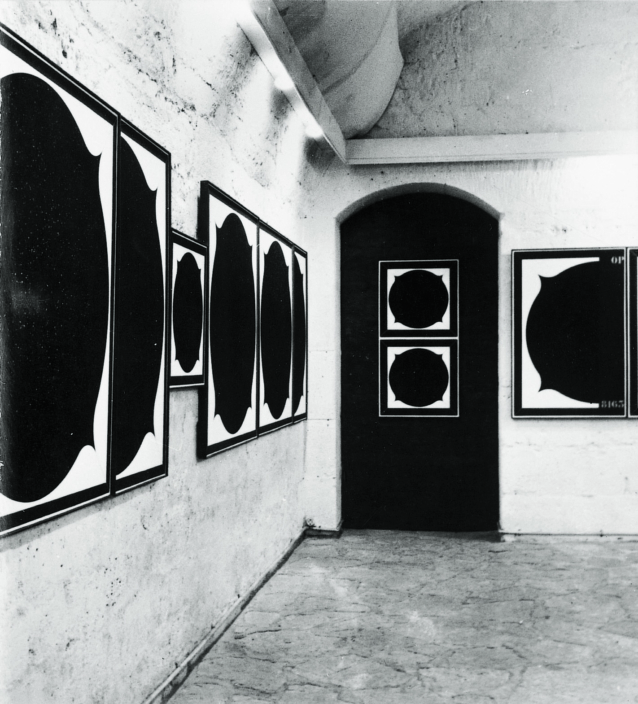

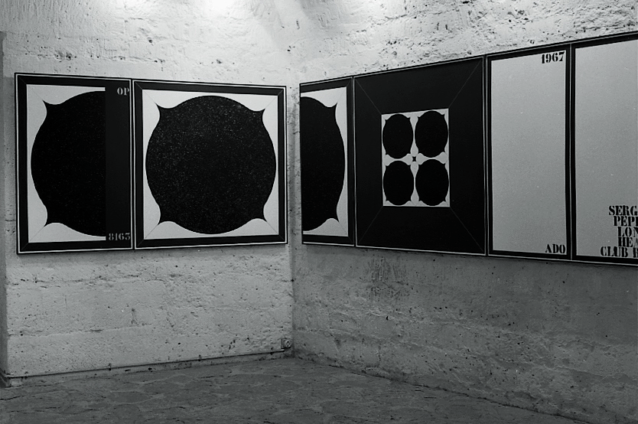

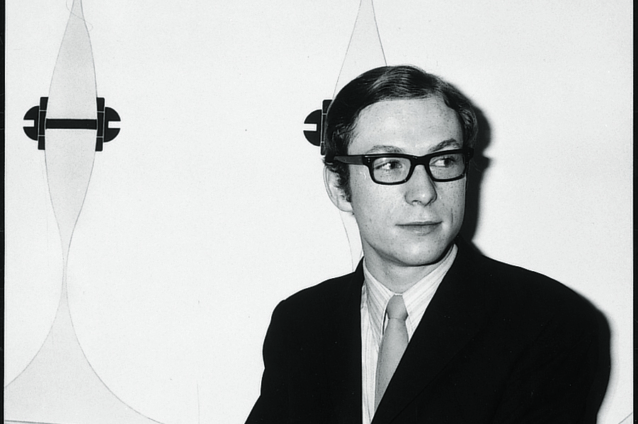

Ado

Recent works

October 5 – November 10, 1967

The japanese artist Ado is perhaps the most modern of the Oriental painters in Paris. His vision is highly refined. All that remains is a pure, stylized, tender line and light surface effects. Beyond the object, we must discover the artist’s personality, his desire to capture the essential, an intransigence but also a vibration that betrays his emotions and anguish. To put it in more journalistic terms, Ado’s paintings are a decade past the end of Op’art. It projects into the future, with a futuristic allure that matches the audacity of our avant-garde couturiers.

Georges Boudaille, Les lettres françaises, October 20, 1966

The four elements

Wind

November 23 – December 16, 1967

Out of Empedocles’ four elements, air is the parenthesis where man comes to remake or lose himself. He’ll need that breathing that’s similar to the tireless beating and rustling of wings. The movement that regenerates. The margin left in white, blue and orange; and you, feet together, ready to jump in. Epic, truly epic! And who hasn’t had his windmills, his horse skinny from bad hallucinations? Green carpet sometimes, it’s your understudy who officiates with a croupier’s vocabulary: the air is your chance! And chance is all about the extreme. So does painting, but the painter isn’t the fakir I mentioned earlier. The painter dances, a little more alone than anyone else, on the surface of his canvas. He has several strings to his bow, but not a chance in hell. In this preface, painting is my oblivion. But surely there’s a painting in the air, even an abstract painting… In any case, the pretext is still very beautiful. And the painting is better than the pretext.

Jean-Loup Majewski, Extract of the invitation card, November 1967