History

The four elements

Fire

February 8 – March 2, 1968

It was by the fire that man could overcome the fears of the night; it was by the fire that he discovered others […], in the shifting play of light that suddenly carves a face we think we know, only to discover it’s different every time. Yes, all social life is organized around this mobility, from war dances to campfires, and including black masses, witchcraft sessions, tribal councils… But fire is also an instrument of torment. Charming and feminine, it is also cruel and deadly. Its song can range from a whisper under the ashes to the great symphonies of the conflagration. […] Fire is also “the moment”. Its past? It’s the material it feeds on: the wood that cracks and splits beneath it, the paper that twists, the brandy that explodes. His future? Nothing or almost nothing, just a few ashes, shapes without contours or eroded, eaten, sick with a disturbing leprosy. It is said to purify, but it casts strange hells, Hiroshimas, over the world wherever it goes.

Jean-Jacques Lévêque, Exract from the invitation card, February 1968

Michel Tyszblat

March 28 – April 30, 1968

It’s said that Kandinsky once discovered abstract painting by looking at a painting that was upside down and on which the sun was playing. Simple, isn’t it? But brilliant. Like Newton’s apple or Galileo’s earth, no one had ever thought of it before. Since then, however, the earth has rotated, crabapples have fallen, faithfully respecting the laws of gravity, and painters have had to turn their heads upside down to paint us abstract things and splash us with the big sun they’ve got there. Right. Let’s start again. The apples fall. The earth spins and spins. Heads fall like apples, potatoes… But what am I saying, is that my head is spinning, and the apples are dancing the carmagnole, obeying nothing but the laws of levitation. Let’s continue. Cézanne painted apples. Michel Tyszblat’s apple is licked, peeled and bitten, but not painted : I dare all the authors of Old and New Realism to find a single apple in his painting.

Marc Albert-Levin, Text from the catalog, mai 1968

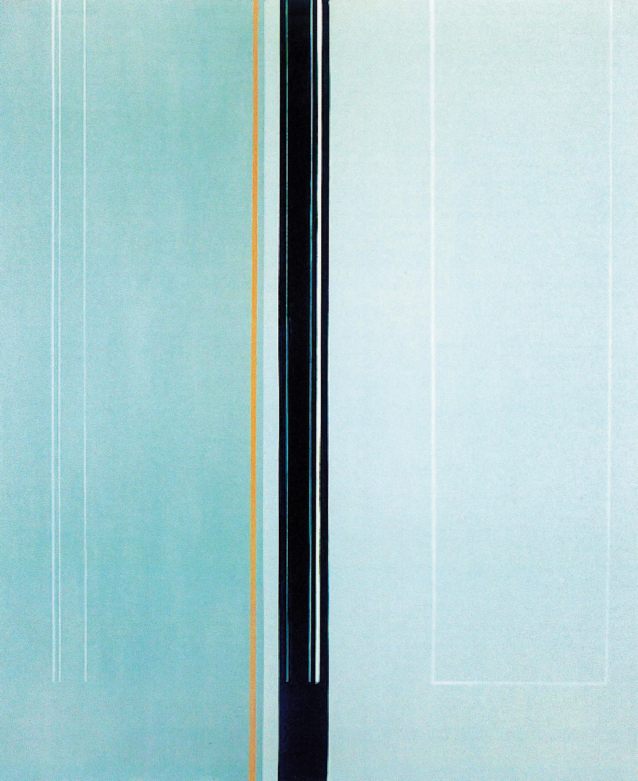

Luc Peire

May 2 – 28 , 1968

In the paintings of his last years, Peire remained faithful to the principle he had established: a painting is a two-dimensional surface in which the manifestations of mind and soul unite, where the clarity of construction and the charm of poetry merge into a single moment. Despite the strict geometrical order of squares, rectangles and beams, poetry rises along a play of sensitive lines; the statics of constructivism are replaced by the liveliness of linearism; in the abstraction of plane relationships, the rhythm and sensitivity of lines live on.

Jaak Fontier, extracts from “Luc Peire, rétrospective”, Stedelijk Groeningemuseum, Bruges, 1966

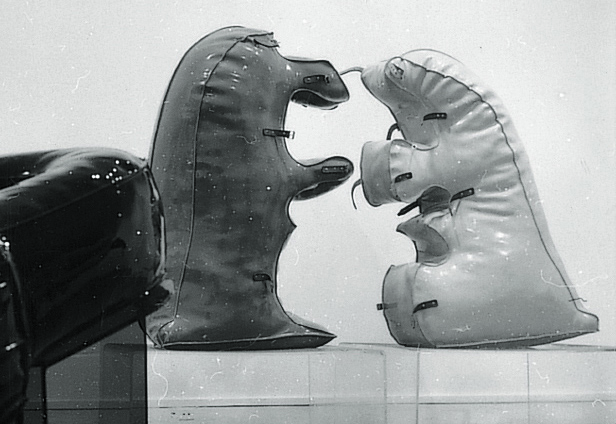

Arnal

October 1 – November 2, 1968

Coming at a time when others were discovering the significant value of the unprocessed object, these works could serve as a transition. The sculptures he is currently exhibiting can also be seen in this light: the lessons of abstract art are not forgotten, despite the artist’s taste for modern materials, for the multiplication of works, and for those simplified forms which come to us from England, and which Parisians were able to see last year with Philippe King’s exhibition. In these works in colored vinyl, sewn together and filled with expanded foam, we find the sensual play of oppositions between softeness and harshness, between penetrating and penetrated forms, between angular and rounded volumes… So many things that are part of the essential vocabulary of abstract art. These dolls for grown-ups appear to be made to be manipulated: their lightness, the utilitarian aspect of the material used, the softness even of the volumes all appeal more to the hand than to the eye.

Grégoire Muller, Pariscope, 2 octobre 1968