History

Daniel Humair

February 4 – 28, 1969

The difference between Humair and the graffiti-makers, the visual lyricists, is that he has the reserved curiosity, even the shameless courage, to reread himself, and that the time that leaves him breathless, strangely enough, participates in the canvas. Using a photographic process, a drawing worn out on the edge of a neglected piece of paper comes back to life and blossoms into the dimensions of a painting. However unbridled his verve may be, unconscious contingencies, excessive habits of chatter and commonplaces, immediately attempt to absorb and resorb it: chronology of narration (the layout is progressive), simplified and conventional forms – the heart, the firecracker, hopscotch – only slightly more awkward and tortured than others, words in the end, definitive compromise. He compartmentalizes the canvas, classifies it, numbers it 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – five. But the phrase – perhaps an insolent jest – spills out of the canvas, loses its meaning or fades away halfway, becoming the witness of a remorse; but a raw green, an apple green, contrasts with a dark, foreboding green, and the conscientious framing bursts into variegated serpentines. The spontaneous image, treacherously, is not necessarily the most sincere. Humair extends and explores it. In spite of himself, he succumbs to the constraints of our language.

Catherine Millet, Preface of the catalogue, January 14, 1969

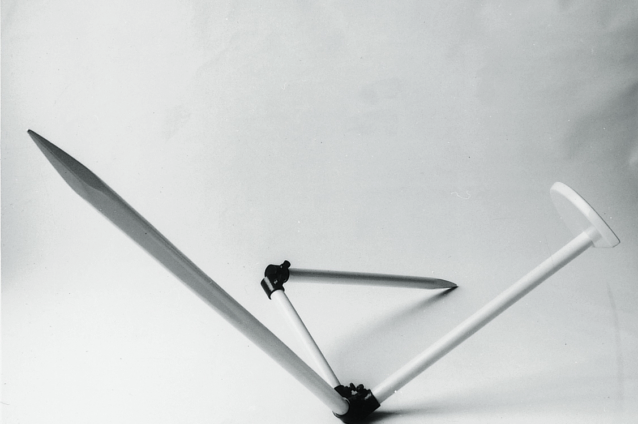

Buri, Dufo, Télémaque, Titus-Carmel

March 11 – April 12, 1969

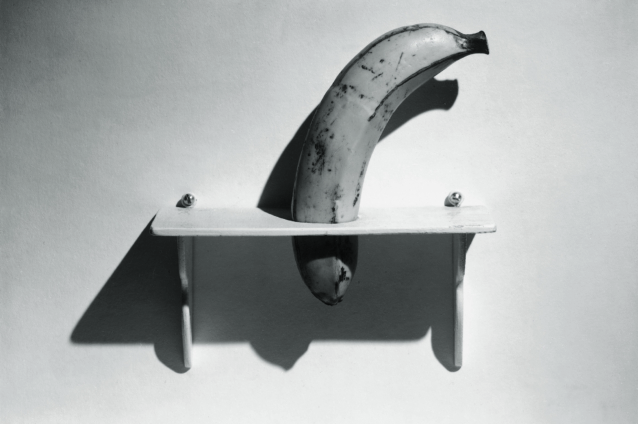

Télémaque a renoncé à la peinture pour développer des assemblages de tiges dans un esprit nautique. On ne se croit pas tout à fait au bord de la mer, mais on croirait bien qu’on va participer à des régates. Dufo, dont j’avais aimé les malles et les cravates peintes sur plastique transparent à la dernière Biennale de Paris, présente une suite de variations sur le thème du tabouret de cuisine, selon la même technique.Mais, de plus en plus, I’objet tend à sortir du cadre de la toile pour envahir I’espace. Cette tendance se situe bien dans Ie sens de certaines recherches actuelles. Samuel Buri, qui a toujours affectionné les jeux de matière et les procédés inédits, expose des cahiers de feutre, de diverses couleurs, découpes. On lit les mots « rot-gelb-blau » taillés en creux dans une matière pelucheuse. Cette expérience dépasse la provocation par ses authentiques qualités plastiques. Titus-Carmel, enfin, accroche des fruits et des légumes, bananes, aubergines, pommes, sur des étagères. Lorsque I’objet est seulement accroché au mur, il acquiert une présence insolite, difficilement explicable, mais qui a sa beauté et qui se situe d’emblée dans Ie domaine de I’art. Pourquoi ? Lorsque Titus-Carmel compose, lorsque ses étagères chargées de fruits sont disposées sur une toile peinte, simplement mais avec sensibilité et talent, alors il atteint à un niveau pictural qui est celui des grands peintres de l’histoire.

Georges Boudaille, Les Lettres françaises, 19 mars 1969

Bernard Rancillac

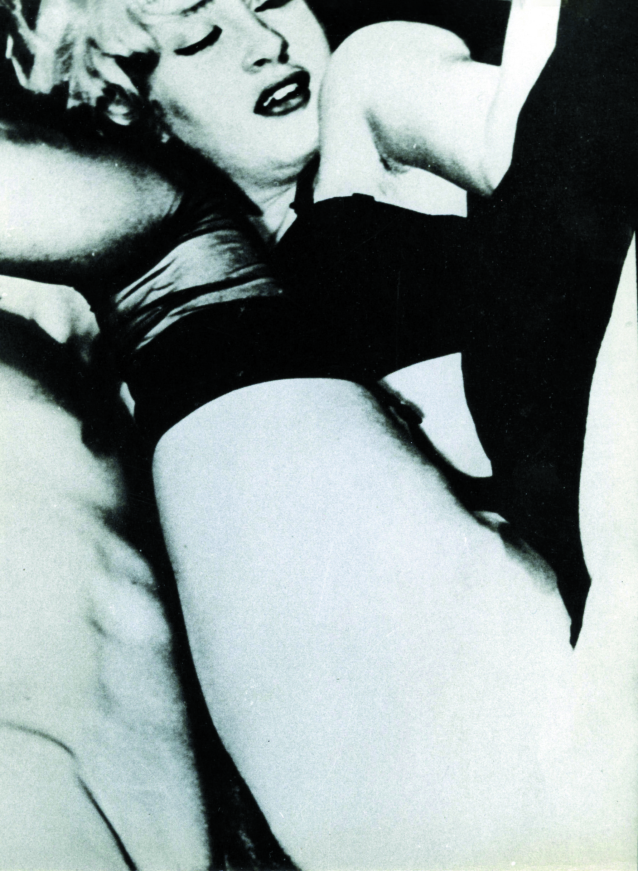

Pornographie

April 22 – May 3, 1969

The Pornographie exhibition (“the last major fallout of May 68 for Rancillac”, notes Serge Fauchereau) announced a new direction. In April 1969, the Galerie Templon was targeted by attacks, and his paintings were vandalized by an outraged public. Enlargements of sexually explicit, homosexual or sacrilegious photos (Les Souris de la sacristie – little girls with a priest) were torn off at the genitalia, while the few “lecherous” spectators were encouraged to answer the following questions in a survey concocted by Pierre Bourdieu: “ Having seen this exhibition, do you think that art can have a liberating effect? Do any of the works exhibited here seem beautiful to you? Would the same subjects portrayed in art be more acceptable to you?

Sarah Wilson, extract from the catalog, Retrospective 1962-2002, Musée d’art moderne de Saint- Etienne, 2003

Martin Barré

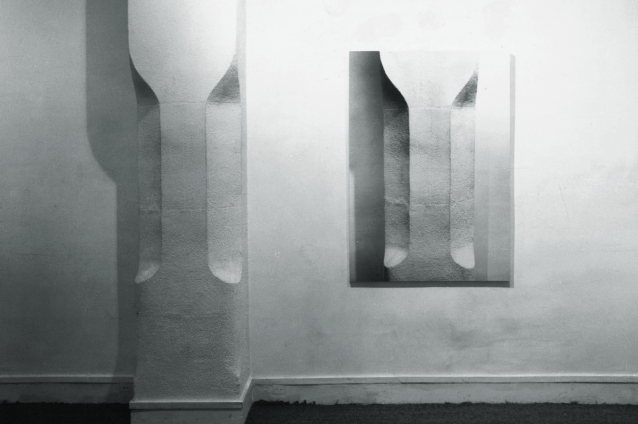

Les objets décrochés

13 mai – 7 juin, 1969

Far from being docile imitations of objects, these images question the very principle of representation (by showing nothing other than what is already there) and create an antimimetic space. Martin Barré has chosen to mark out the frontier of imitative art, to draw a fence around it, an exemplary approach: the white canvas has always been the limit towards which his work has tended; but this limit retains its raison d’être precisely insofar as it is not reached, insofar as a difference remains between it and the canvas on display, a difference that engenders meaning. Almost nothing is more valuable than nothing, silence is more important than silence. The absence of the object – like the absence of the painter – can only be said through the movement of their disappearance, not by showing a blank canvas. Painting is born of approximation, of play within play, of difference within repetition. But that’s not all. On these canvases, we don’t just see the objects we see next to them; we also see how we see them.

Tzvetan Todorov, Préface de I’exposition, mai 1969

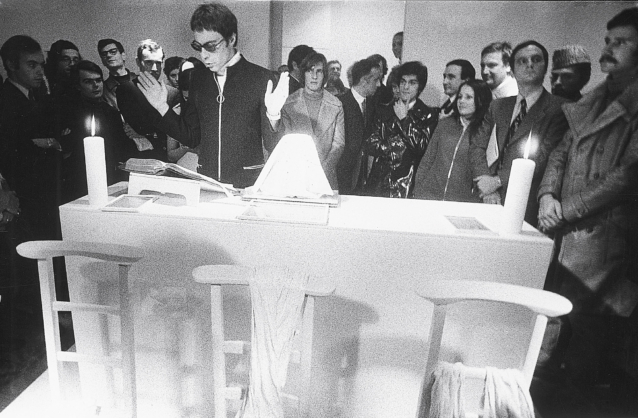

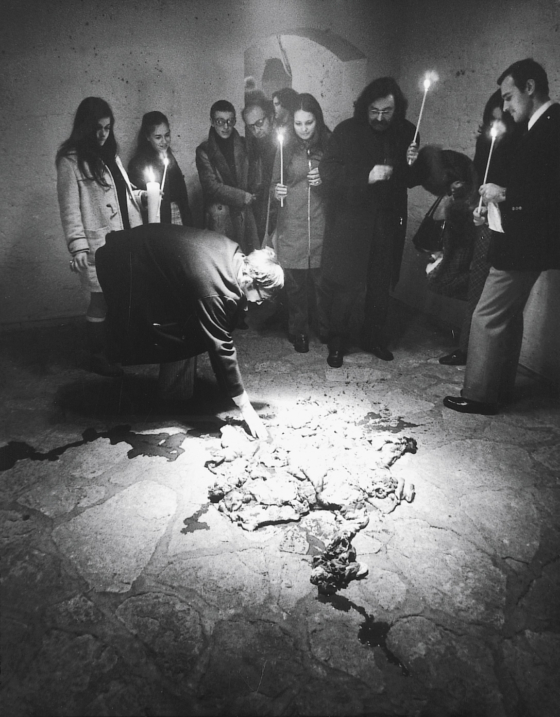

Michel Journiac

Messe pour un corps

November 6 – 22, 1969

In France, Michel Journiac is the only artist who can still cause a scandal. Since he first appeared on the scene a little over a year ago, his work has been vandalized and criticized, but people are talking about him, loudly and increasingly loudly. He was seen as an artist who had fallen from the rain, when in fact he was the most lucid, the most aware and, without doubt, the most successful of all the artists who had decided to turn their backs on neo-realism and all forms of more or less conceptual expression. There’s something admirable about Journiac’s creative escalation. After taking over the venerable Billettes cloister, washing away all the salvageable products of contemporary art and tracking down the artistic implications of bodily freedom, Journiac has just launched a “mass for a body”.

François Pluchart, Combat, November 17, 1969