History

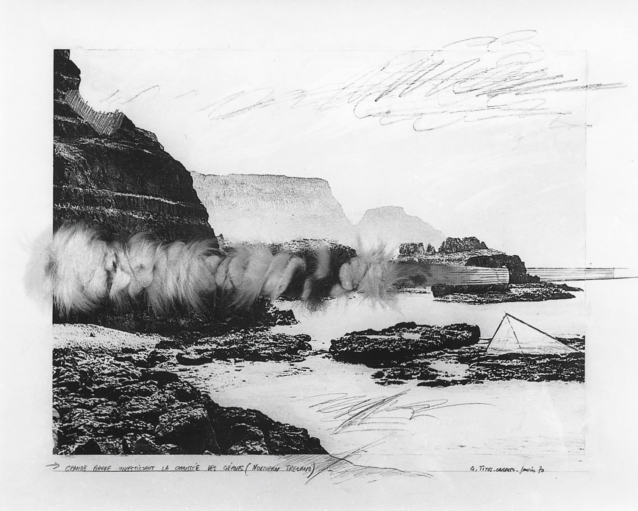

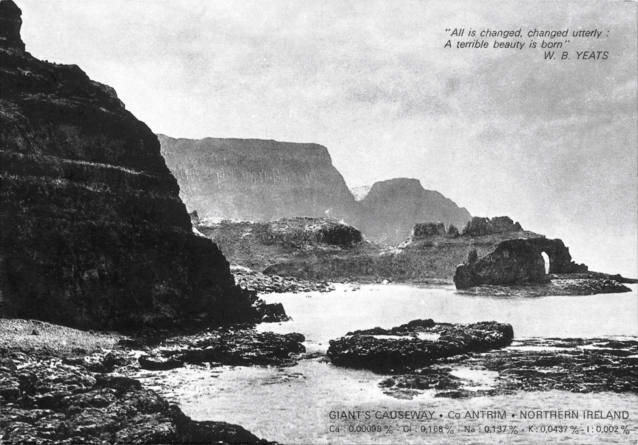

Gerard tITUS-cARMEL

GIANT’S Causeway

January 13 – 31, 1970

What is the link between the use of artificial fruit and that of odors? With bananas, my problem was to identify the relationship between a “true” and a “false” conception of the same reality. At the Distances exhibition, I exhibited a set of sixty bananas, only one of which was true, but on the evening of the opening, they were all still identical. In other words, we weren’t trying to find out whether they were real or fake. There were sixty bananas, that’s all, and it was only when one of them began to ripen, to take its place in time and suffer the consequences of browning and rotting, that we deduced that there was one real banana, and that the others were implicitly fake. […]

The use of smell allows me to get to the limit of this. I choose a site: “the Giant’s Causeway”, and artificially recreate its smell in the laboratory. Obviously, what will be in the gallery will not be the “Giant’s Causeway” – the site – but sodium, potassium, iodine, etc. The imitation of the site. So there are two ways of approaching it, both as subjective as the other: one, which was for me to find myself one day on the actual site (to have experienced a certain emotion there, but that’s not the point) and the other, which lies in its subjective – artificial – approach. But in the relationships that are established between an existing nature and its desire to imitate it, which in a way goes beyond it, there can be no exact correlation. It’s in this gap (model/imitation) that we can find a kind of cleavage from which a poetic phenomenon can be extracted. The more ambiguous and subtle, the more epidermal, the more vivid the poetic force.

Catherine Millet, Les lettres françaises, January 14, 1970

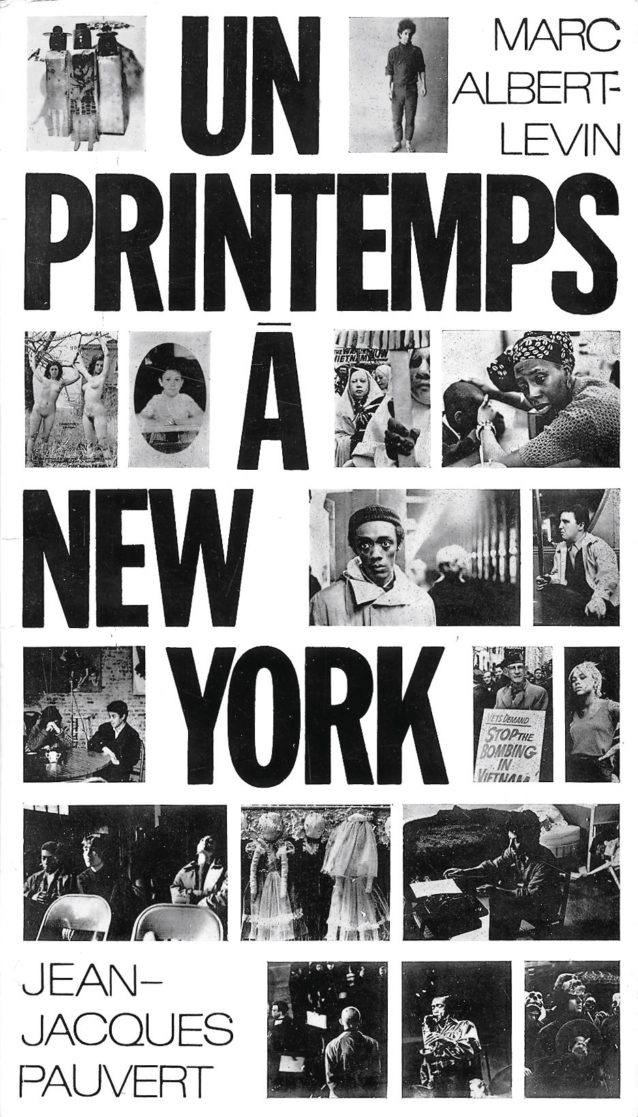

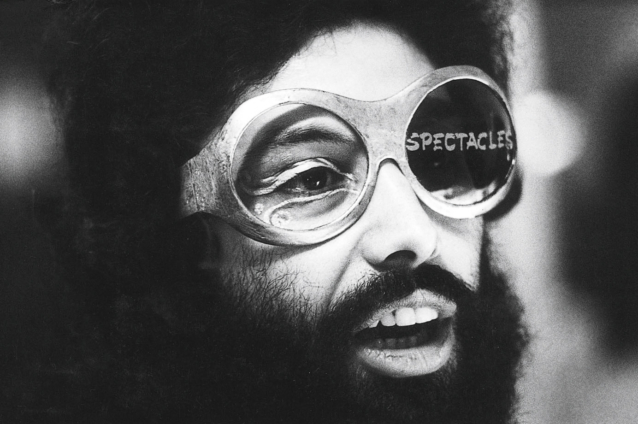

Marc Albert-Levin

Un printemps à New York

February 24 – March 14, 1970

It’s possible that the word will remain irreplaceable for some time to come, if only to convey new concepts and establish their existence. It’s certain, however, that despite the talent of a few writers, literature has not produced works as strong today as the paintings of Klein or Raynaud, the films of Warhol and the whole of underground cinema. Pop art literature quickly proved to be far inferior to the plastic creations of which it sought to be the equivalent. Marc Albert-Levin has twice sought to abolish this rivalry between image and word: first, by writing short works published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert (Un printemps à New York, Tour de Farce) that are an explosion of reality, a mixture of events, images and sensations; second, by exhibiting his books in a gallery where he has reconstituted his familiar universe at the crossroads of painting, words and jazz.The result is a kind of permanent happening around his tastes and everything that’s new today in the field of thought forms aimed at a contemporary definition of art.

Marc Albert-Levin also writes for today. A critic of art, of many art forms, Marc Albert-Levin is a pleasure to read. It’s the privilege of a work full of present-day flavor.

François Pluchart, Combat, 9 mars 1970

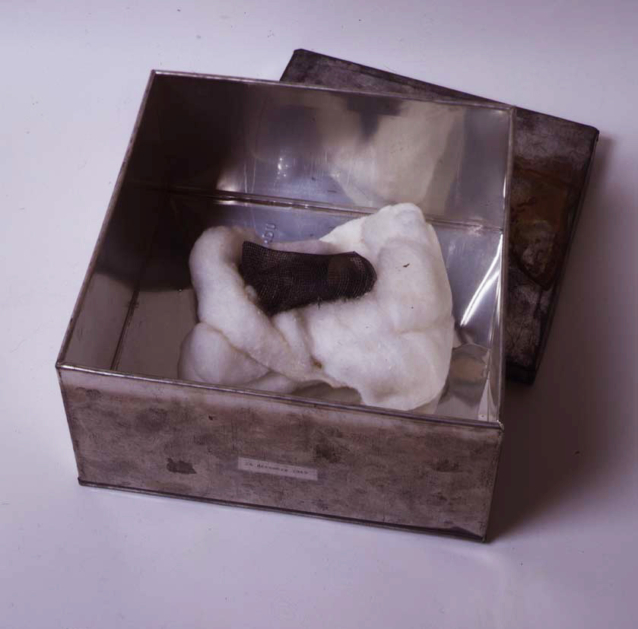

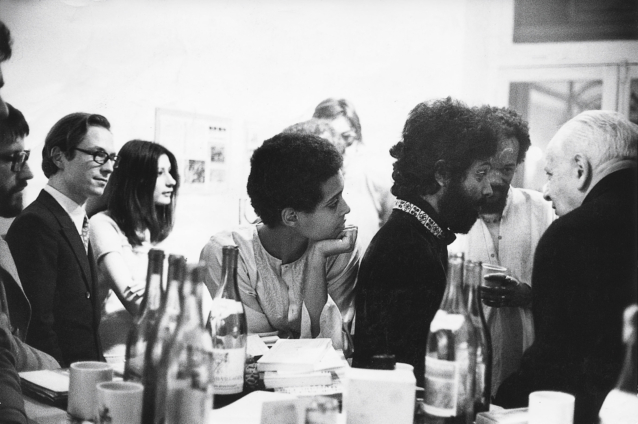

Christian Boltanski

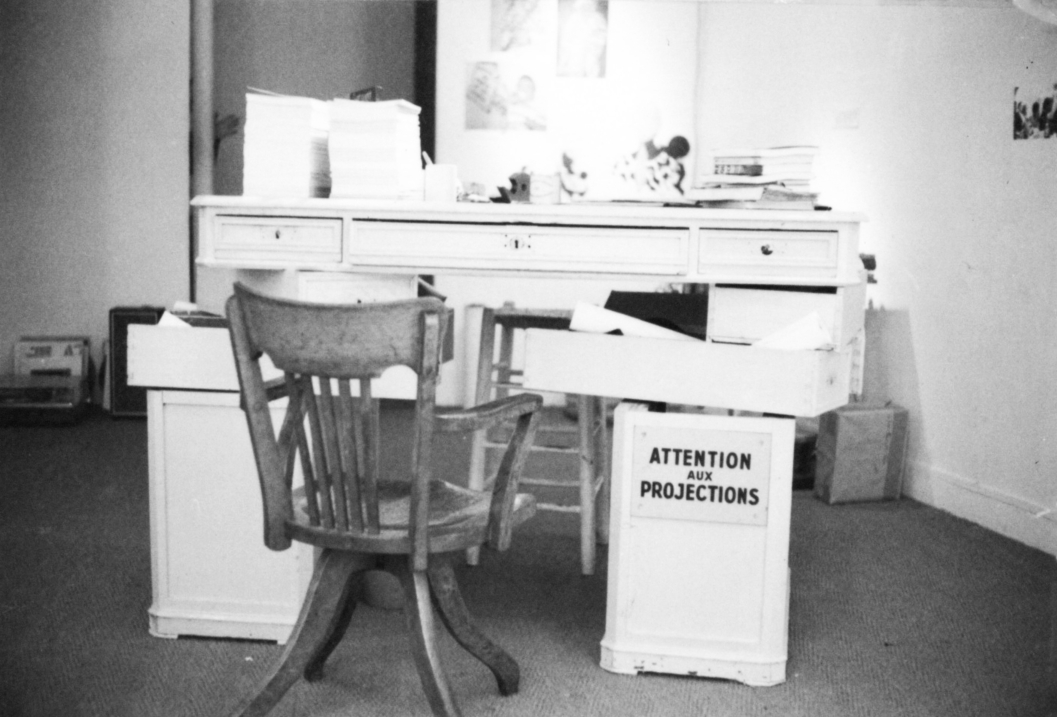

Local I

March 17 – 21, 1970

I suppose a lot of people will mistake Christian Boltanski’s exhibition for a display of conceptual art. This is not the case, at least within the realm of conceptualist doctrine. If Boltanski is reminiscent of Beuys in certain respects, if he resorts to means belonging to the promoters of non-art (Ben and the Fluxus group, in particular), his work is essentially autobiographical. He sees himself as the center of his creation. His human story, his life, are his only subjects. Boltanski seeks to tell the whole story of himself, in the totality of his existence, strong and weak moments intimately intertwined, identical in quality and effectiveness. The ideal for Boltanski would undoubtedly be to live forever in the field of a camera that would objectively capture every fact, every gesture, every accident. It is this totality of existence that would constitute the true experience of a thought. Boltanski knows the difference between reality and its appearance, the profound incompatibility between life and its outcome.

In fact, here’s what he says about this state of mind: “I wanted to put my life in a box. With this in mind, four months ago I bought two hundred empty half-teen cookie tins from the Giraud company in Bondy. Each box was to contain a moment from my life. It was a beautiful project… Unfortunately, they don’t contain my life, but objects that only reflect the time I spent making them. Boltanski’s adventure, made up of interventions that diverge in their formulation, is one that cannot leave one unmoved. At the crossroads of neo-realism and conceptualism, Boltanski attempts an original breakthrough: that of a work that is at once testimony, observation and art object all at once. At a time when conceptualist manifestations are taking place and will continue to do so, Boltanski wants to take a distance and to keep his eyes open.

François Pluchart, Combat, March 23, 1970

Jean Le Gac

Local II

March 24 – 28, 1970

On the ground, a block of rough masonry (on a square base, 1.20 m square) made of thick hollow bricks with rough cement joints, the low height of the walls (barely 40 cm above the ground) suggests that every effort has been made to make the interior of the block easily accessible. A frame of solid planks, set in a greyish gangue, conceals the narrow, empty dwelling where the floor is just above ground level. A faint crackling sound can be heard, but cannot be located. It’s impossible to remember how the cord is fastened behind the hidden face of the masonry. This whitish cylindrical cord has the softness of tallow-coated cord. Weakly stretched to within a short distance of the brickwork, it penetrates deep into the ground.

Jean Le Gac

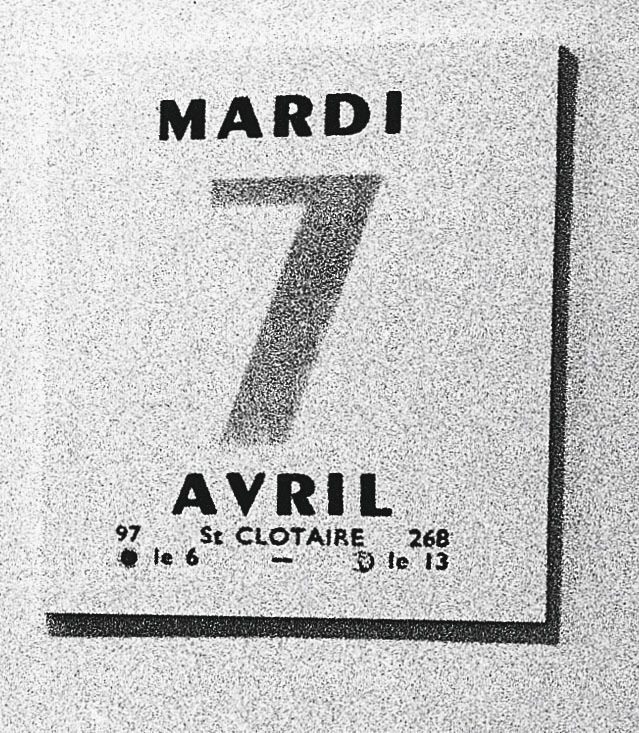

Martin Barré

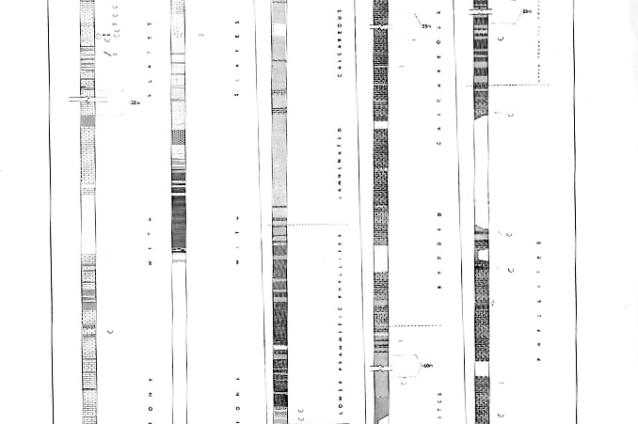

Calendrier

April 7 – 25, 1970

Strange as it may seem today, Martin Barré’s exhibition at Galerie Templon in May-June 1969 was one of the first manifestations of conceptual art in France, and this was before a series of major international exhibitions – notably in the USA, Germany and Switzerland – had drawn public attention to this new chapter in the history of the index. But if Barré now criticizes his work from this period – 1969 to 1971 – speaking in retrospect of its lack of originality, we have to admit that it was far from banal in its context: indeed, he stopped his conceptual vein altogether as soon as he became aware of the extent of this fashion abroad. […]

Barré’s exhibition, entitled Les objets décrochés (Unhooked Objects), is fully in line with the conceptual trend: the few photographic panels arranged in the Templon gallery are not hung on the walls in the conventional way, but in close proximity to what they record, i.e. services, operating furniture and architectural features of the gallery, all the more visible because it is “empty” (entrance door, wall corner, pillar, old wooden door, spotlight, staircase banister, signature book). […] Barré’s second exhibition at Templon in 1970 featured the same constative mode and literalization. After the indexical de-familiarization of the gallery space, here comes the de-familiarization of the exhibition time: on the gallery walls, a series of photographic enlargements of pages from one of those little calendar pads on which you can read the day’s date in large letters, are spread out in the flattest possible way. The series begins with the page for April 7, 1970 and ends with that for the 25th of the same month, thus marking the actual duration of the exhibition; each photographed page is at once identical and different, as are the days of the year. Real space, real time – these are the least subjective parameters an artist can deal with for an exhibition, the ones that lend themselves most easily to an indexical recognition process.

Groupe

May 26 – 13 July, 1970

The “Groupe” exhibition at Galerie Daniel Templon exhibits works by Ben, César, Christo, Lucio Fontana, Raymond Hains, Joseph Kosuth, Jean-Pierre Raynaud and Bernar Venet.

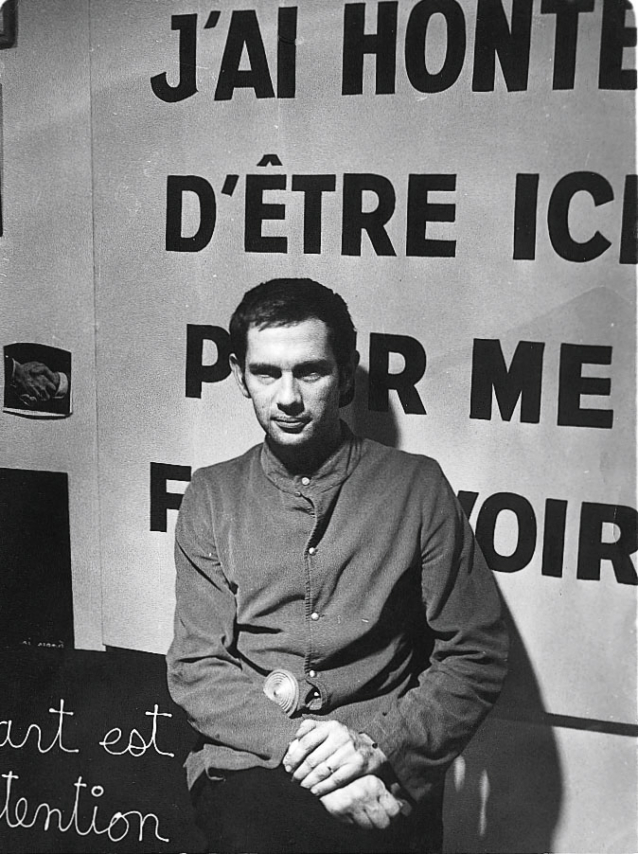

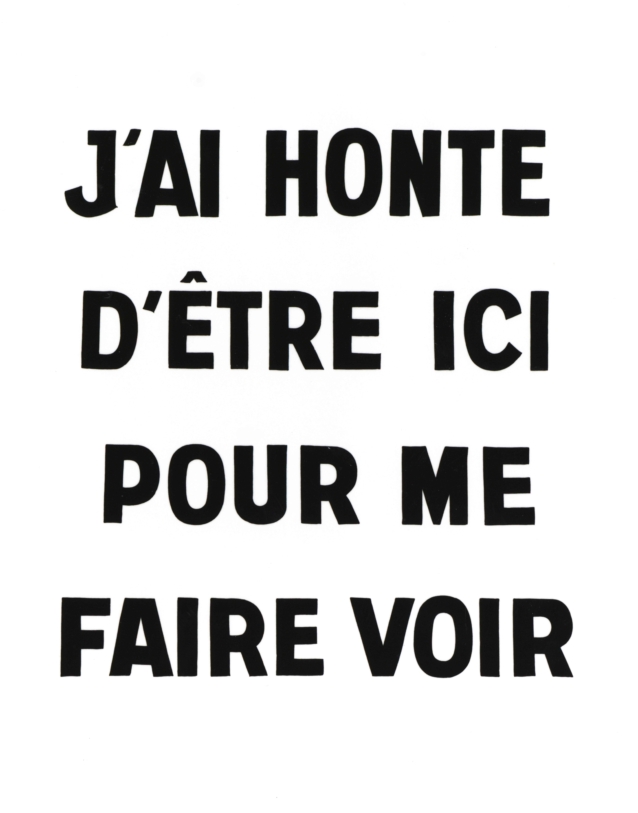

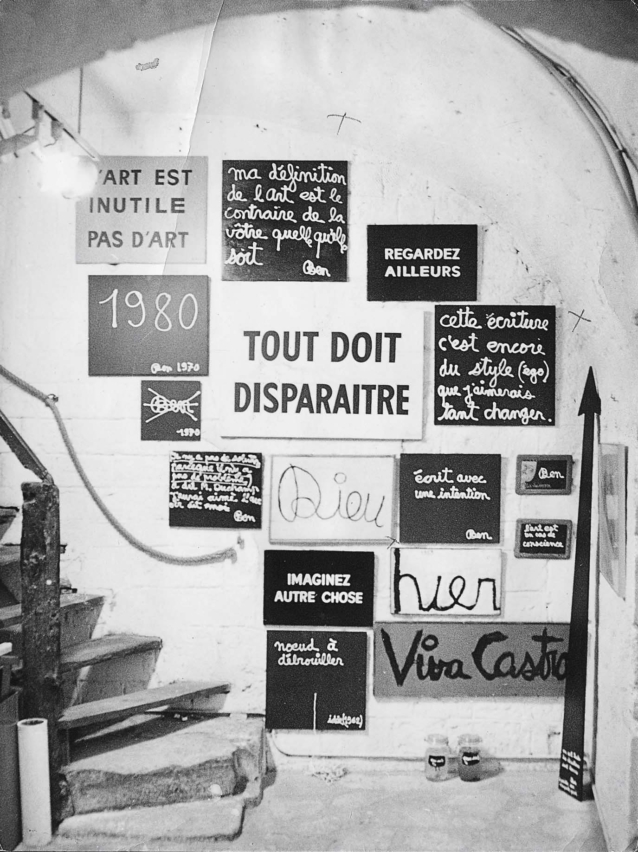

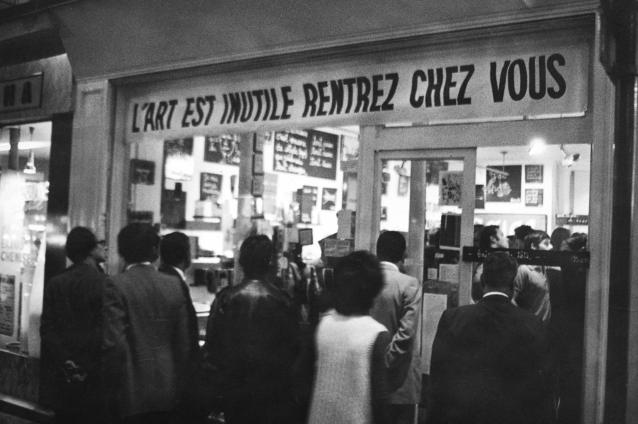

Ben

L’art est inutile, rentrez chez vous

September 22 – October 10, 1970

1) You are invited to the Galerie Templon, 58, rue Bonaparte, on September 22 from 6 p.m., until October 10, 1970.

2) I, Ben, am exhibiting over 60 ideas in the form of objects, paintings and publications; I’ll be inaugurating the release of my book Ecrit pour la gloire à force de tourner en rond et d’être jaloux. To celebrate, I’ll be making a gesture at 7:45 p.m. on September 22.

3) One of the key ideas of the exhibition will be that of truth, because I believe that truth in relation to the work (its price, its color, its size, etc.) and truth in relation to the act of creation (fiddling, jealousy, ego problems, ambition) can change art if they are stated.

4) My current position on art: A) You have to do something new to change the situation as much as possible. B) To do something new in substance and not just in form, I have to change what everyone else is doing. C) Everyone creates for glory, to be different from everyone else; Rembrandt found something for glory, Duchamp exhibited a bottle holder for glory, Cage said everything is music for glory. D) So to bring something new, I have to change the purpose of art, the fulfillment of the ego (glory). E) Even if this intention is motivated by my ego (a snake eating its own tail).

5) Agreements with Daniel Templon: artistically, total freedom to write, say and do what I want.

6) My self-criticism: I’m ashamed of wanting to be the greatest, of not being the greatest, I’m dishonest when I say that you have to destroy the ego to make new art and that I do this to satisfy my ego so that people will talk about me, thus transforming a real impulse into just another little trick. I recognize that my broad-minded “everything is art”, “one thing is not more important than another”, is just another form of hypocrisy to try to be superior to others by encompassing them. I admit to having been influenced directly or indirectly by Georges Brecht, “Life is art”, by Duchamp, “Everything is art” by Isou, the megalomaniac (in spite of himself). I recognize that what would please me would be to become important, that I’m jealous, ambitious, petty.

7) My worries: I shouldn’t delude myself like a drunken woman, I shouldn’t abandon my store to find myself sitting beak-in-the-water at the Coupole, croaking with the Parisian frogs.

8) My pretensions: I have more ideas than all the conceptual artists and others put together, who generally have only one or two. […]

9) Appreciation of me: Arthuro Schwarz said to Tobias: “Ideas like Ben’s, I get a thousand in a day”. Biga on my last column: “You’re too petty”. Flexner said, “He didn’t steal five ideas, he stole forty”. Boltanski told me in Montpellier: “It’s very interesting to play the clown”. […]

10) Suicide interests me because it’s one of the solutions to the ego’s cul de sac in art. Furthermore, I consider that every individual should have, from the age of 18, the inalienable right to take his own life, if he so wishes, and that society has a duty to provide him with a clear, quick and painless death. To achieve this, we need to set up suicide centers, just as we have cultural centers. In these establishments, anyone wishing to commit suicide would have to reside for 48 hours, during which time the representatives of society – in this case the state, religion, business, political parties, etc. – would be able to convince the individual not to end his or her life. If, however, he persists in his desire to die within 48 hours, then society must provide him with the means, i.e. the place and instruments, to carry out his own death himself – without a hitch. In the meantime, and given that these suicide centers don’t yet exist, I thought it would be a good idea to publish a popular book at a very low price, containing all the practical and serious advice anyone could need to avoid a botched suicide. I don’t know the statistics, but I do know that a lot of suicides are not carried out voluntarily, just as a lot of people stay alive not because life attracts them, but because they’re afraid of suffering or don’t know how to go about it. […]

Ben, Invitation text, 1970

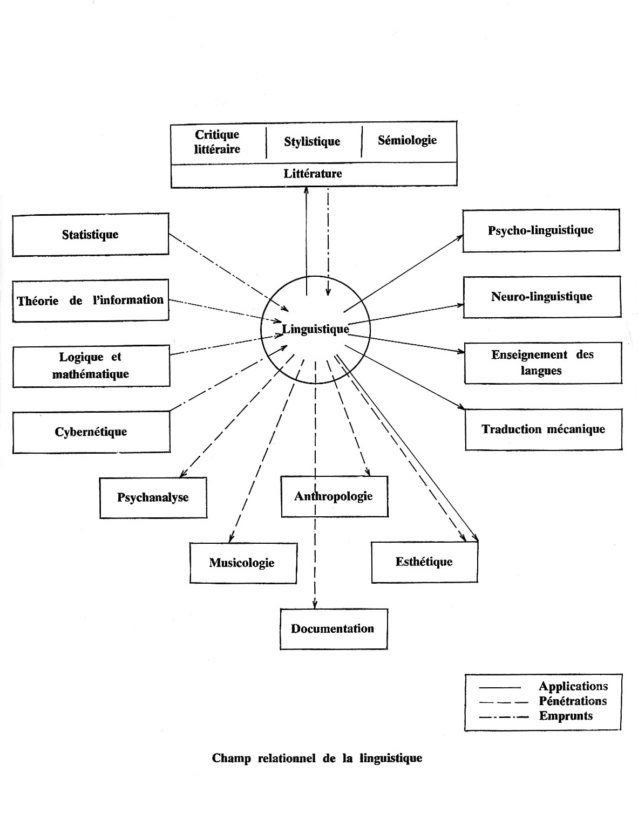

Concept Théorie

November 3 – 21, 1970

The present exhibition includes only texts recorded in brochures, enlarged photographically or reproduced on magnetic tape. However, these texts do not describe phenomena that are natural or intellectual, mysterious, poetic, uncontrollable, irrational or unattainable, and which, because of their superficial approach, have come to be known as “conceptual art”. It’s not just another variation on the visual arts, possibly involving the outright negation or concealment of all visual preoccupations (what generation after generation has come to call “anti-art”). The twelve artists taking part in this exhibition are laying the foundations for a different kind of activity.

Catherine Millet, excerpt from the exhibition catalog, October 1970

The “Concept Théorie” exhibition at the Galerie Daniel Templon exhibits works by Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin, Victor Burin, Ian Burn, Harold Hurrell, Alain Kirili, Koslow, Joseph Kosuth, Emilio Prini, Mel Ramsden and Bernar Venet.

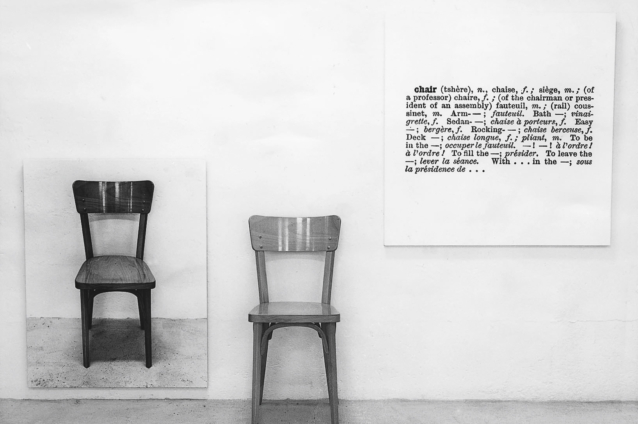

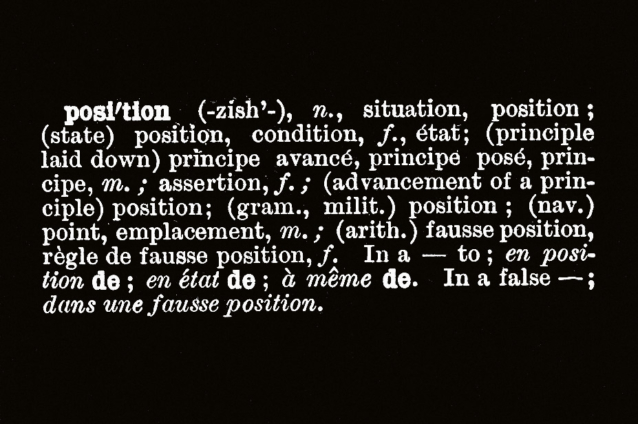

Joseph Kosuth

The seventh Investigation

November 30 – December 31, 1970

Proposition eight of the seventh investigation consists of a small collection of excerpts from four books: the memoirs of General de Gaulle, Jacques Duclos, André Maurois and Marshal Zhukov. The choice of these books is based entirely on the fact that the genre of “memoirs” is highly characteristic of French literary production, and is in absolutely absolutely of no way significant. For the sake of functionality, Joseph Kosuth always adapts the form of the information he provides about his work to the context in which that information is perceived. At the end of the collection is a codified table which, when studied and analyzed in relation to the reading of the texts, reveals the logical, mathematically progressive way in which Joseph Kosuth has reclassified the extracts. For each extract, we find the author’s name, the title of the book, the page number and the paragraph number.

As with the logical problems exhibited above, Joseph Kosuth appeals to the reader’s deductive and memorizing capacities, but without, of course, resorting to associations extraneous to the proposition itself. When it comes to Joseph Kosuth, it’s impossible to speak of specific works. A series in the Thesaurus refers to those that have been, are, will be exhibited elsewhere; understanding the reorganization of book excerpts triggers multiple possibilities of analogy. Joseph Kosuth’s proposals highlight the patterns of relation – cultural and linguistic references – into which every work of art fits, even though the traditional understanding of the artwork has denied them, locked in the criteria of originality and the incomprehensible. […]

The work of Joseph Kosuth and others like it, and this is their main characteristic, achieves a theoretical scope that breaks radically with the artistic gestures and attitudes that, since Duchamp, have served as a method of investigation.

Catherine Millet, Flash Art, February 1971