History

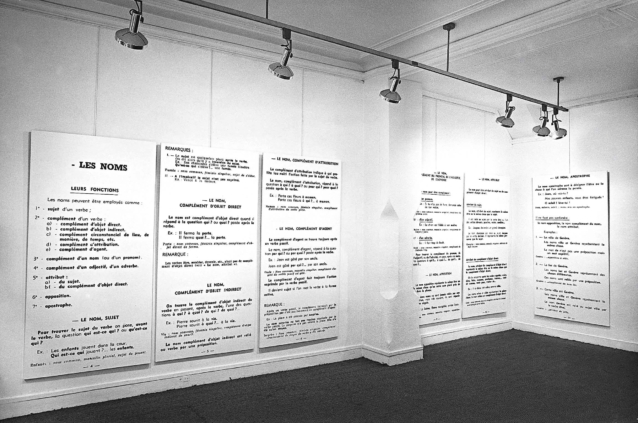

Bernar Venet

January 12 – 30, 1971

Bernar Venet’s intervention in the development of art over the last five years has led to the affirmation of an objective, rational approach, sweeping aside the idealistic tradition and paving the way for the most uncompromising research currently being carried out in conceptual art. From 1965 onwards, Venet produced illustrations, first handwritten, then photographic, of pages from scientific books, always chosen from among the most recent and comprehensive. To make these selections, Venet enlisted the help of specialists, sometimes even asking them to give lectures. His presentation no longer satisfies the ambiguity of a style – the artist’s interpretation of the data of reality – but the clarity and functional adaptability of the most diverse media: blow-ups, magnetic tapes, discs, books, magazines, etc. Nothing is added to the artist’s style. Nothing is added to the original meaning of the proposal; it admits of only one level of reading. In the current exhibition, Venet is focusing on language, exhibiting several chapters of a grammar book.

Catherine Millet, Les Lettres françaises, February 17, 1971

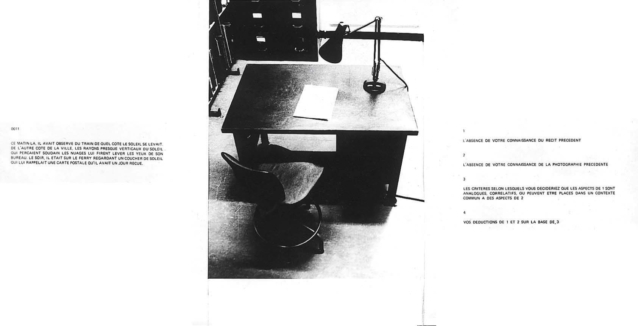

Victor Burgin

Performatif Narratif Piece

February 2 – 20, 1971

The particular object of art is not the physical world sui generis, but the social mediation of it by means of an arrangement of signs, through which its predominant orientation is not analytical and descriptive (like scientific linguistics), but synthesizing and normative. […] We could ask for a description by which the artist’s activity could be distinguished from other activities. […] An answer such as, for example, the artist is the one who creates things that are pleasing to the eye would be inconsistent, since many things that are pleasing to the eye are produced in fields other than art. My answer to this question […] takes into account the codes we use to communicate with each other.

Victor Burgin, excerpt from Work and Commentary, 1973

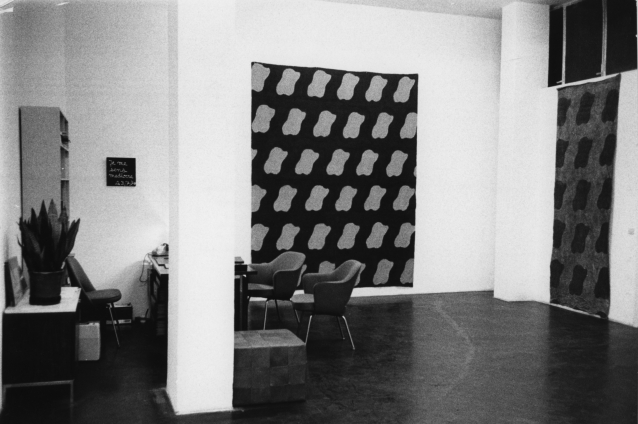

Louis Cane

February 23 – March 13, 1971

It could be said of Louis Cane’s work that he doesn’t make a “sheet”, but first and foremost a “canvas”. From one to the other, this passage is not self-evident: it’s a path that leads from sensitive/visible knowledge – the folds of the sheet – to logical/scientific knowledge, complex and endlessly repeated, of the canvas – through the folds, cuts, seams and colors; sheet/canvas; the two edges, internal and external, at work in painting. This knowledge cannot be acquired outside the activity of production: productivity as a return to the seed of meaning and subject – vertical canvas/sheet – and as the engendering of the pictorial fabric – horizontal sheet/canvasA process of reading/writing, from sheet to canvas and vice versa, through texture – a double operation using the thread of the fabric as a formal method of communication (geometry, surface structure) and the thread of the knife, the chisel cutting into the color, as a differential method of production (number, volume of colors). Engendering the canvas as the effect of its own cause (metonymic causality), a calculated operation whose sum is not without remainder: color being the reserve opening to the repetition of its different imprints (metaphors), in a transfinite series where each canvas can be the same and – contradictorily – other; a structure/color, surface/volume relationship that is not cause and effect but difference.

Marc Devade, Excerpt from the exhibition catalog, 1971

Wolf Vostell

Environnement-Happening électronique

March 16 – April 3, 1971

Happening: methods and means

Even in the seemingly most insignificant contents of his happenings, and down to the smallest events, Vostell reveals the atrocities of everyday life, and forces our worn-out sensibilities and senses to admit that idyll no longer exists. His means are things that are done and happen every day – they happen this way or that way in our daily lives, or make us feel heavily threatened that they could at least happen this way. The participants in the happenings act with things that are part of everyday life in a big city: the simplest objects as well as the most complex instruments.

Environments

In Vostell’s “electronic ungluing environment”, exhibited at the Venice Biennale, you walk on a floor of broken glass, entirely covered with other pieces of glass, which produces extremely unpleasant noises and shrill, tense sounds. Vague, unrecognizable things begin to move everywhere in this half-darkness; voices and the rustle of appliances fill the room – and always the screech of one’s own footsteps.

Jörn Merkert, excerpt from “Environnements-Happenings 1958-1974”, Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1974

Art Language Press

Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin, Harold Hurrell

April 11 – May 29, 1971

The Lecher system consists of two parallel wires carrying a high-frequency radio wave. The wave is reflected at the far end, producing static waves. At voltage and current antinodes, i.e. where voltage and current differences are greatest, this phenomenon can be detected by appropriate means. These voltage antinodes are separated by half a wavelength, as are the current antinodes, but they are displaced by a quarter wavelength along the wires. In other words, for a wavelength of 1 m, there would be an antinode every 25 cm, alternately voltage-current, voltage-current, etc. At certain points, which are the voltage antinodes, the voltage difference between the two wires will be at its maximum. At other points, current antinodes can be detected by connecting a 1.5-volt electric lamp bulb to both wires. The bulb holder is connected to two rigid wires and inserted into a test tube which acts as a handle. Holding the hand carefully away from the Lecher wires, the bulb is pushed along the connecting wires and the points where the bulb lights most brightly are noted.

Exhibition’s text, 1971

John Gibson gALLERY

Vito Acconci, Christo, Dan Graham, Peter Hutchinson, Will Insley, Allan Kaprow, Dennis Oppenheim

June 2 – 19, 1971

Two-step drawing transfer. From Dennis to Erik Oppenheim, 1971

While I draw a line on Erik’s back, he tries to reproduce his movement on the wall. My activity stimulates a kinetic response from the sensory system. So I’m drawing “through” him. The sensory shift or disorientation is the difference between the two drawings, and can be interpreted as elements activated during the process. Because Erik is my son and we share certain biological traits, his back (as a surface) can be interpreted as an immature version of mine. In a sense, I’m getting in touch with my past state.

Two-step drawing transfer. From Erik to Dennis Oppenheim, 1971

As Erik draws a line on my back, I try to reproduce his movement on the wall. His activity stimulates a kinetic response in my sensory system. So he’s drawing “through” me. The sensory shift or disorientation is the difference between the two drawings and can be interpreted as elements activated during the procedure. Because Erik is my son, and we share certain biological traits, my back (my surface) can be likened to a mature version of his. In a sense, he’s getting in touch with his future state.

Dennis Oppenheim, excerpt from Dennis Oppenheim catalog, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1974

Ben

Ecritures 1958-1966

June 22 – July 10, 1971

A number of typically Parisian events round off the season. First of all, an exhibition of Ben’s “writings” at Galerie Templon. After long being considered a minor artist, Ben has finally established himself as one of the key artists of the last ten years. A true heir to the Dada spirit, he has conceived his work as a reflection on art and as a way of life. Handling humor and irony to perfection, he has written dozens of scathing aphorisms on panels (writings) and performed hundreds of actions and “gestures”. His megalomania rings hollow, and if he poses as a genius, it’s to further destroy the traditional image of the master.

Bernard Borgeaud, Pariscope, June 7, 1971

The opening of a branch in Milan

October 1971 – July 1976

For a few years, between September 1971 and 1976, the Galerie Templon possessed a branch in Milan. The initiative resulted from two observations: on the one hand, there were only very few French collectors of contemporary art liable to acquire works from Daniel Templon; on the other hand, the old practice of foreign collectors coming to Paris to buy art was dying out. Templon’s conclusion was that he could make things easier for his clients by opening a sister gallery in Switzerland, Germany or Italy. At this time, the last-mentioned country offered several advantages, the most striking of which was its dynamism and openness with respect to contemporary art. In Milan, Templon occupied a first floor apartment of almost one hundred square meters on Via Monte di Pietà – a stone’s throw from La Scala- in which he staged à number of exhibitions with the assistance of Daniella Dangoor […].

Julie Verlaine, Daniel Templon. Une histoire d’art contemporain, 2016

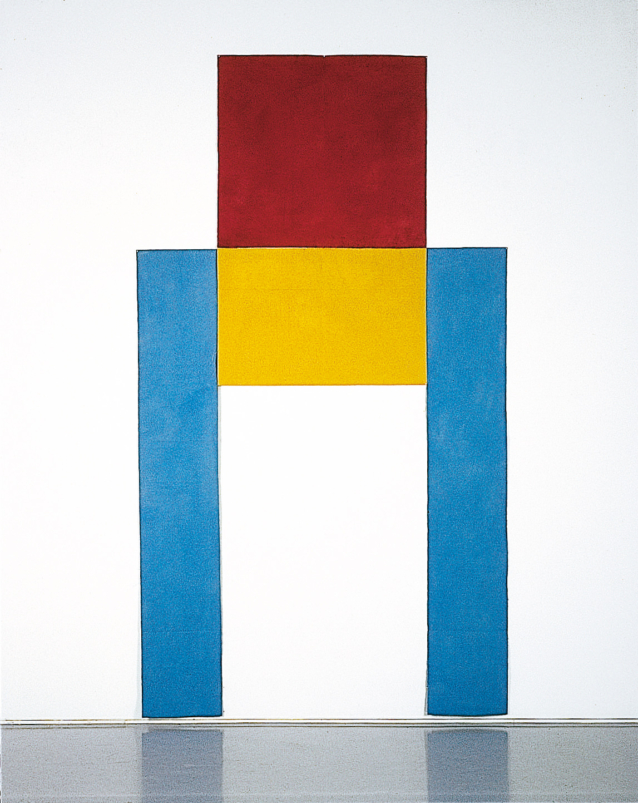

VIALLAT, JUDD, BARRÉ, DEVADE…