History

Louis Cane

Recent works

January 17 – February 17, 1973

The question of the place of the ideology of painting in the social structure inevitably leads the painter to ask himself the question of the uniqueness of his work […], and of the history and role of this special nature; in other words, to move within a history that is both unravelled and repressed, to think of himself in the dialectic of sedimentary and metamorphic strata that constitute him not only in the real, but as a reality in his relationship to the real. After Braque and Picasso, modern French painting cut itself off, in the academic Ecole de Paris, from the history of contradictory forces that had produced it; what I’m trying to point out here is that today, in painting as in literature or music, we are witnessing the return in force of the “monsters” of history, and the birth of the powerful achievements that we can always expect from the struggle with these “monsters”. The question of the place and role of painting in the social structure reintroduces Louis Cane’s work to a historical problematic that his predecessors in France have developed. What began logically enough as a narrowly French perspective on the avant-garde activism of the painters of the late ’50s, has now shifted to a focus on the ideological role of symbolic forms in history.

Marcelin Pleynet, art press, march 1973

Victor Burgin

Passages

10 – 28 April, 1973

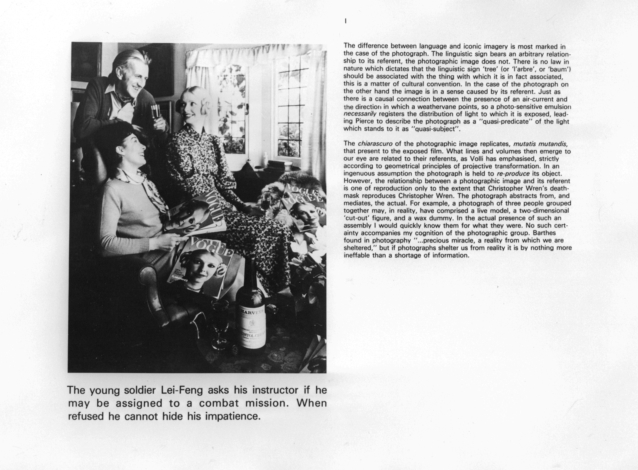

Burgin’s works are based on a Barthesian approach to the semiology of photography (images borrowed from advertising), combined with texts of various origins: for example, in Lei-Feng, 1974, an advertisement for sherry, a narrative evoking the zeal of a young hero of the Chinese revolution, and a theoretical text by the artist dealing with semiology. This tripolar combination mobilizes the viewer’s critical sense, destabilizing his habits of looking and thinking. These brief descriptions clarify Burgin’s position as a conceptual artist. Burgin shares a number of positionswith Joseph Kosuth and the artists of the English group Art & Language in particular, to which he belongs often hastily and wrongly assimilated to the group (he did not participate in its work, and wrote only once in the magazine Art-Language, questioning the group’s positions).

Like these artists, he believes that art is meant to communicate information, not produce objects; the privileged position enjoyed by the art object, its claim to autonomy and the hegemonic position it attributes to the visual world, are not acceptable to him.

Joëlle Pijaudier, extrait de Victor Burgin, Passages, Musée d’art moderne de Lille, 1991

Giorgio Griffa

Recent works

2 – 26 May, 1973

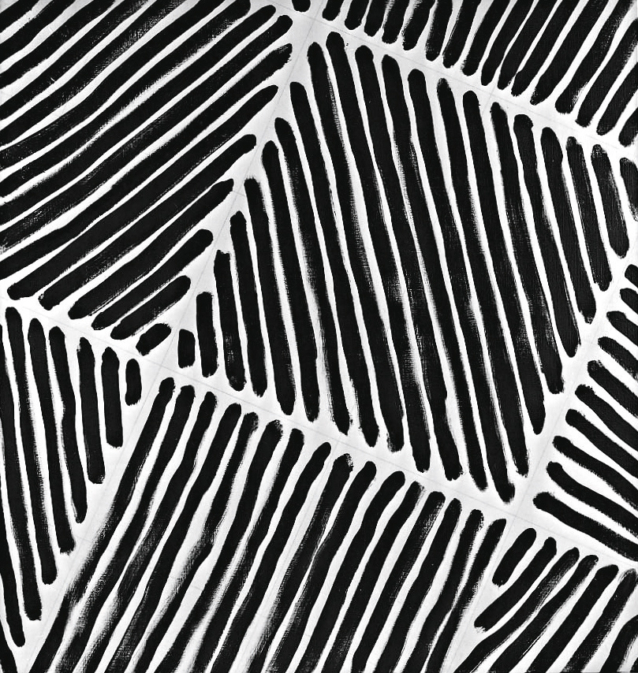

When it comes to the painter exploring his own art, I don’t think I’m that kind of person. I’m not hoping for an in-depth analysis of the painting. Analysing implies active, critical behavior, research into the means employed, their material connotations and virtual possibilities. I don’t think my work betrays any such attitude. I’m merely an executor, just like the other concrete instruments that contribute to bringing color to the canvas.My direct intervention stops before that: until yesterday, it stopped at the moment when I established the rules for each work. What happens around this “pictorial practice” […] forces me to question my own attitude to the canvas.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Je me rends compte que prétendre choisir à chaque fois une seule parmi le nombre infini d’hypothèses organisatrices de la couleur sur la toile reste au fond, dans mon cas (car il s’agit là d’un problème personnel, pas d’une généralisation), une prétention intellectualiste et « sophistiquée ». Je me rends compte que, si je tiens à porter ce travail au maximum de conscience, il me faut éliminer cette prétention. I’m convinced that there is an infinite and indeterminable variety of truths in every aspect of reality, which can be brought to the conscious level using a cognitive method such as the one I’ve chosen: availability. In this case, however, the pretension of changing the rules of the game each time becomes useless and harmful: the process would simply be reproposed from a different point of view and under a different aspect. […]

Giorgio Griffa, La Riflessione sulla Pittura, septembre 1973

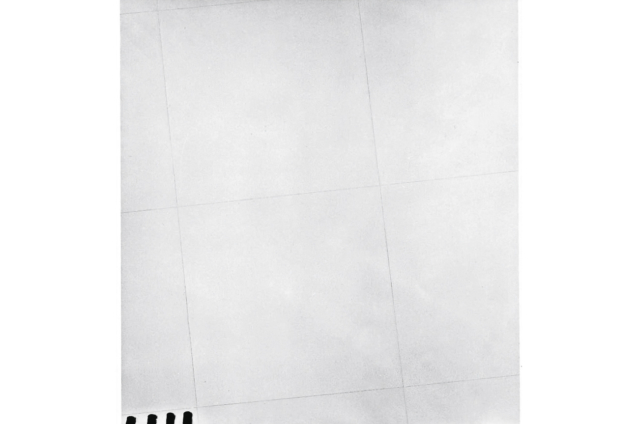

Martin Barré

Recent paintings

May 29 – June 30, 1973

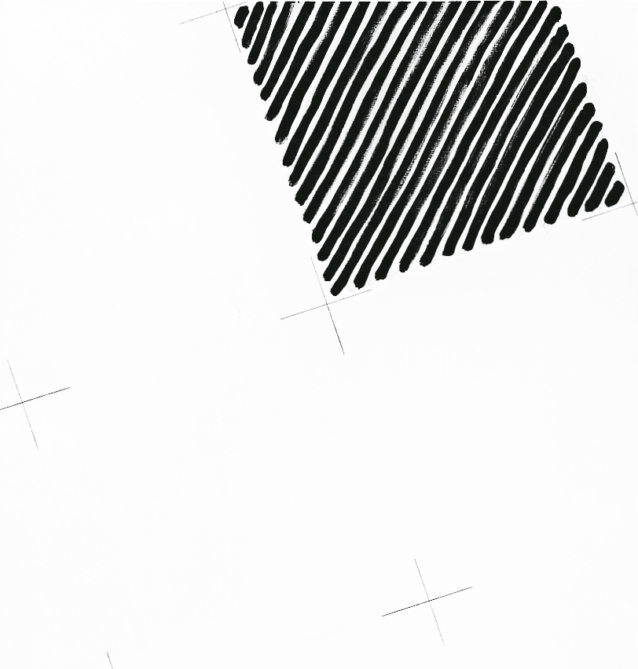

The meaning of this word, “figure”, has been misunderstood, as the adjective “figurative” has been taken from it to mean “imitating the world of objects”. For a figure is intransitive: it does not represent something, but is composed of the relationships of its parts, forming a pattern; it implies within itself the realization of what it is. Painting doesn’t need to be figurative – to depict objects – but it necessarily affirms the mode of its construction: it is figurative. It is this figurality of painting that the present exhibition by Martin Barré highlights (for those who had forgotten it). This is not to say that it represents a break with his past; on the contrary, echoes of his previous exhibitions can be discerned, each of which now appears as an almost clinical, necessary exploration of the ingredients of an overall hypothesis: the unity of twenty years of production bursts forth through the present synthesis.

And the present canvases make us aware of the figurality of his painting through what appear to me to be their two major constants. The first is that this is literal painting. The painting is not true in relation to the world or the painter, which it cannot be; it is a truth of the painting in relation to the painting itself. For example, it is a flat object: it would be futile to look for an effect of perspective or depth in the paintings exhibited here. The depicted surface is isomorphic to the depicted support. Or again: the painting is never closed in on itself; it becomes what it is through its relationships with other paintings, present (in the gallery) or absent, […] with the whole human experience of vision. The painting is therefore, by definition, a fragment. Here, this fragmentary character is immediately offered to view: the division represented inside the painting does not coincide with that imposed by the frame of the painting itself; the embrasure of the painting shows us only a fragment of the great grid that runs through the entire pictorial space.

Tzvetan Todorov, Text of the invitation card, 1973

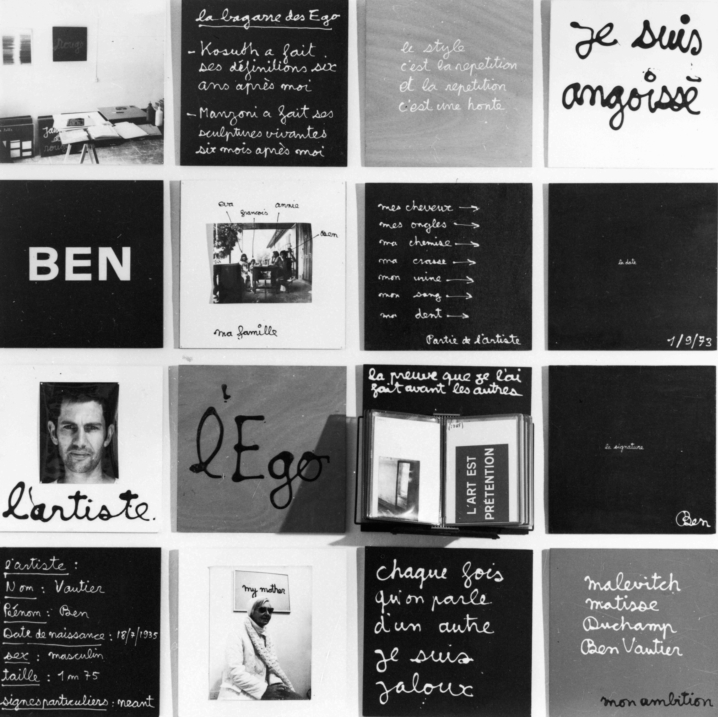

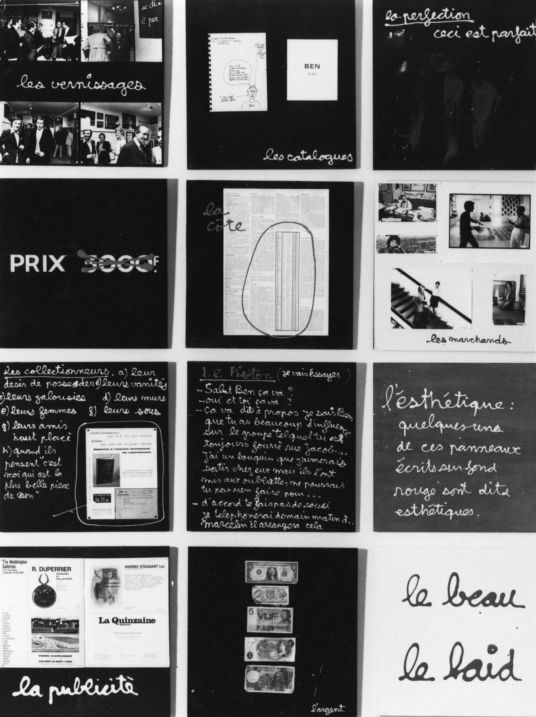

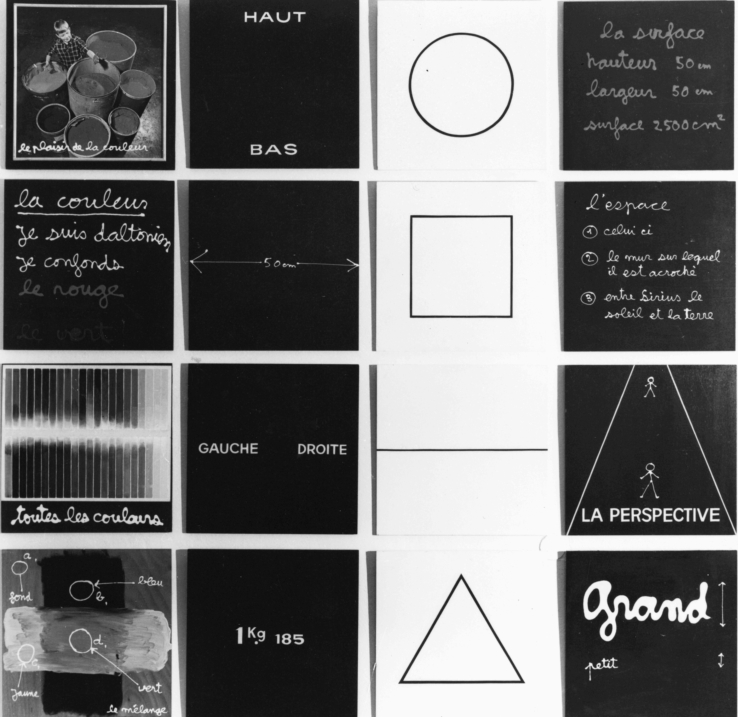

Ben

La déconstruction de l’oeuvre d’art

September 15 – October 30, 1973

Maîtres d’abstraction

Ellsworth Kelly, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Larry Poons, Frank Stella

October 6 – 15 December, 1973

The latest Stella works, without being sculptures, are three-dimensional; Noland, famous for his long, smooth, matt bands of color, and Poons, whose subtle geometry bordered on artoptic, are now blurred, shaded and mixed, in the same way that Olitski abandoned solid colors as early as 1965. And even Kelly, author of one of the very first rigorously symmetrical paintings (Bridge Arch and Reflection) in 1954, is showing apparently unbalanced constructions in his latest exhibitions: “Color-field”, “Hard-edge”, “Shapedcanvas”, “Post-Painterly Abstraction”, Europeans have had a hard time accepting these vast expanses of uniform, monochrome paint, which they found primitive and unrefined.

Now that this painting has been acquired (as the new wave of painting in France demonstrates), armed with a brand-new knowledge – “painting takes place in a two-dimensional space” – we shouldn’t look too skeptically at this evolution of Americans towards working in a more ambivalent space, at once flat and deep. Plutôt, rechercher ce qu’elle signifie, dans le contexte actuel, par rapport à leur production antérieure. Ne pas juger si cela est « meilleur » ou « moins bien » – la critique d’art n’est plus de décerner des palmes – mais comprendre quelle connaissance nouvelle elle nous apporte, immanquablement, de leur peinture.

Catherine Millet, art press, novembre 1973