A conversation with Kehinde Wiley

Interview

Led by curator Claudia Schmuckli, this conversation with Kehinde Wiley revisits the artist’s exhibition ‘An Archaeology of Silence’ at the de Young museum (San Francisco) and explores his new body of work that sheds light on the brutalities of American and global colonial pasts.

CS: I was curious about when you went to school — in San Francisco and then Yale — at what point did you realize that your personal project of becoming an artist and finding a career could link to a social project that has become so much part of your work?

KW: It’s a really interesting question. If I paint a bowl of fruit, it would be an African- American in the late-capitalist 21st century painting a bowl of fruit, right? Are you ever capable of escaping a rubric through which people filter what you do? I think the answer is no. So you just have to proceed, and make the work that you make. What I do is all based on radical contingency: for instance, these moments of chance where I find someone who’s minding their own business walking through the streets, I tap them on the shoulder, and the next thing is they’re hanging in one of the great museums. That is a responsibility. It’s a social project, but it’s also personal. If you really think about my entire body of work, it’s a self-portrait.

CS: You put yourself into these situations where you had to make yourself very vulnerable. That’s an interesting part of the work: how you emphasize your own vulnerability in making the work and how you comment on that vulnerability within the work.

KW: There is something to be said about the vulnerable — this show is about the vulnerable. So much of my work has been about the strident, the self-possessed, and the actualized. It was a play in power, playing through the power that people have seen themselves through historically.

In this show, I wanted to zoom in on every individual detail — a cell phone or a shoelace or the tracks of a weave, small little things that deserve to be elevated, as in an old Dutch painting by Frans Hals.

This is our version of a time capsule, it’s a way for us to say “yes” to the people who happen to look like me, to people who are oftentimes seen at arm’s distance. I don’t want the arm’s distance. I want to bring you close, and I use scale as way to deal with that. I want the paintings and the sculpture to dominate you as a situation.

But then, there are these quiet moments with little sculptures in which you contemplate these Black bodies as being actual loved, cared-for, actualized people.

ENTOMBMENT (TITIAN), 2022, bronze,

32 × 111 × 81 cm – 12 3/5 × 43 5/7 × 31 7/8 in, edition of 3 + 1 AP

CS: You have explored the subject before – in ‘Down’ in 2008 – this idea of the fallen figure, the prone figure. Since 2008 to this iteration, what has changed? And what motivated you to put great emphasis on sculpture in this body of work?

KW: The first and most important question is that you’re dealing with the powerless and you use institutional devices to create a sort of change system around powerlessness. But when you are dealing with Barack Obama, you don’t just get the job.

You sit in the Oval Office with Barack Obama. He wants to know how you are going to translate his image into something that is enduring, but that also blasts through the tradition of the staid thing.

So he says, “let’s do it my way: I want to lean forward, I want my collar open. I want my hands open. I want this sense of I belong to you, I’m a man of the people.” But there was also a desire on my part to ask, “Well, who are you and who are your people?” We did deep research into botanicals from Kenya, Indonesia, Hawaii. We wanted to follow his trajectory as an internationalist. I thought the biggest story was that people didn’t really recognize his complexity. I wanted his complexity to become the star of the show.

He got his way, and I got my way – portraiture is a battle back and forth. But most of my work is not portraiture in that sense, it is rather a kind of conceptual process.

During the Covid period, I was in Dakar, Senegal and I spent about two years thinking about Black bodies being seen differently. George Floyd had just been slain. I thought about my show ‘Down’, and there was something about it, a gravity to seeing prone black bodies. I wanted to create something where you see this prone, broken moment but monumentalize it in a way that you could slowly come to the sculpture, come to the painting, and see some humanity there.

CS: I would love to hear you talk about the importance of sculpture in this work because you bring in another iconographic language.

KW: Sculpture is different. Sculpture is painting on steroids. Sculpture says, “Ping! I’m in the world, you’ve got to deal with me.” In fact, sculpture becomes precisely the kind of space-taking person I’m talking about. You are literally creating a moment.

For this show I wanted sculpture to be epic and terrible – not epic and wonderful. Because what we’re dealing with, as a community and as a society, is epic and terrible. And I want art to do more than point: it has to have a heart that beats and responds to the beautiful and terrible world we live in.

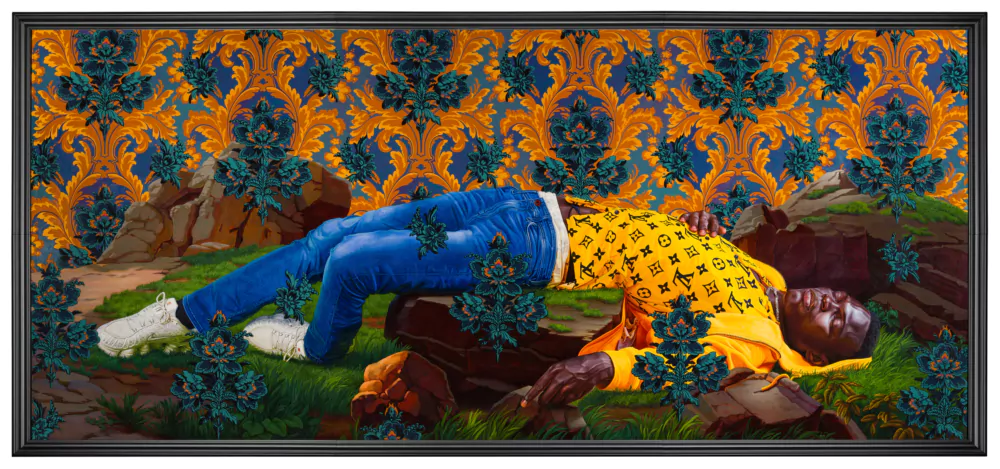

FEMME PIQUÉE PAR UN SERPENT (MAMADOU GUEYE), 2022, oil on canvas, 363 × 790 × 10 cm – 142 7/8 × 311 × 3 7/8 in

CS: Let’s talk about this interplay between the monumental and the intimate that you establish with the sculpture. On the one hand, you are working within the tradition of the monument – a language associated with empire – whereas the smaller sculpture registers more in terms of the reliquary and the sacred.

KW: It’s all sacred. You’re making a really interesting point, because art-historically there is a difference between scales. Large scale was generally commissioned by the state – like a great David painting in the Louvre, dedicated to Napoleon’s conquests. This is a scale we understand: history writ large, ego writ large.

I want to weaponize that power, that language, for my paintings – but sometimes in unconventional ways, using a very large- scale language to talk about something very intimate and tiny. Who is she? Why is she here? One moment in time gave rise to her being in front of the artist.

It’s not about historic turns in times, but about what is huge and historic and turning when you pay attention to the people who oftentimes have not been seen. That is the revolution, that is the history, that is the war.

CS: What was it like for you to make this work in Dakar? As you embarked on that journey, did you have an idea of where it would land?

KW: I had absolutely no idea. I was stuck in Dakar. I say “stuck”, but it was a blessing.

I had to rely on everything I knew to be true – what I was taught as a young art student. I had to pull in every single aspect of this, the material aspect of paintings. There were no studio assistants, no help, it was just me and this painting.

We created paintings based on the people in my community. As we were socially isolated, all the models that you see in the show are people who were in the small group of artists who knew artists.

Dakar is also a place where I can get away from white people – and I don’t mean to be cheeky. A weight comes off your shoulder the minute the plane lands, the minute you see Colgate ads with all-black families. A sense of being in which you don’t have to second-guess what it means to be alive. A lot of you in this room never have to second-guess what it means to be alive – but a lot of us do. “How do I look? Am I presenting myself the right way? Am I looking threatening?” All of that just falls away. It’s a bunch of negroes dealing with a bunch of negroes, and I love that.

CHRISTIAN MARTYR TARCISIUS (EL HADJI MALICK GUEYE), 2022, oil on canvas, 210 × 301 × 9 cm, 82 2/3 × 118 ½ × 3 4/7 in

CS: One crucial aspect of ‘An Archaeology of Silence’ is that it is a global story, it really is a subject that is not exclusive to the US. Can you talk about your thinking about the role of technology within that?

KW: The role of technology with regards to Black bodies is instrumental but not necessarily revolutionary. We know we’ve been slaughtered and killed, and that state- sanctioned violence was the common state of affairs. But social media allowed the rest of the world to see it.

Covid was a situation in which people were in their homes and had nothing else to do but think about what was going on. And they started thinking about Black folks.

There was an opportunity in Venice to pull the resources I have to create one of the largest shows that I’ve ever been invited to do, the biggest show and the best ideas. And my best ideas surround how we get seen and how we get subsumed sometimes.

CS: Do you feel that there is a difference in terms of presenting the work in Venice and presenting it here in the US and in San Francisco in particular?

KW: San Francisco is for me like the biggest homecoming ever. This is the place where I learned to paint. Venice was Venice. Venice is the biggest character in the room. In Venice you don’t have the show without this story of art history and its background.

Now when it comes back to San Francisco, this is now my story, this is now my stuff. It is also meaningful to be at the leading edge of what is happening with museums right now: we all have to understand that being cultural gatekeepers is a huge responsibility.

What we say in monuments is “we collectively believe in this.” That is why they’re so terrifying — if they’re the wrong monument. The huge horse you see in this exhibition is the one that was ridden by one of the colonialists. And I said, let’s take the faces of young Black men from the last 10 years using computer technology to mold all their faces into one face, and that’s the face of that person who’s riding that horse.

Coming to San Francisco is also coming to the place in which radicalism exceeds, it survives. The Black Panther Party finds its home here, the queer rights movement finds its home here. We are a people of openness. Many of us. And I think that sets the tone for who I later go on to become.

‘An Archaeology of Silence’, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, 59th Venice Biennale, 2022

_

‘Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence’, de Young/ Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco until October 15, 2023. Curator: Claudia Schmuckli.

Caudia Schmuckli is curator in charge of Contemporary art and Programming at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Previously she was director and chief curator of the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston, where she forged a reputation as a pivotal figure in the presentation of contemporary art. Before coming to the Blaffer Art Museum, Schmuckli worked at the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. She holds an MA in art history from the Ludwigs-Maximilians-Universität in Munich.

This transcript shares edited excerpts from the conversation that took place, in public, at the De Young in San Francisco on March 18,2023. All right reserved © Fine Art Museums of San Francisco.

Born in 1977 in Los Angeles, Kehinde Wiley lives and works in New York. Examining issues of racial and sexual identity, his works create collisions where art history and street culture come face to face. The artist makes eroticised heroes of the invisible, those traditionally banished from representations of power. His work reinterprets the vocabulary of power and prestige, part politically-charged critique, part an avowed fascination with the luxury and bombast of Western symbols of male domination.