A Woman Artist, Body and Soul

Interview

On the eve of the inauguration of her monumental sculpture Mater Earth, artist Prune Nourry meets philosopher Camille Froidevaux-Metterie, who has just published the novel Pleine et douce. The two consider the question of the body, the feminist dynamic, pro-creation, and the balance between the particular and the universal.

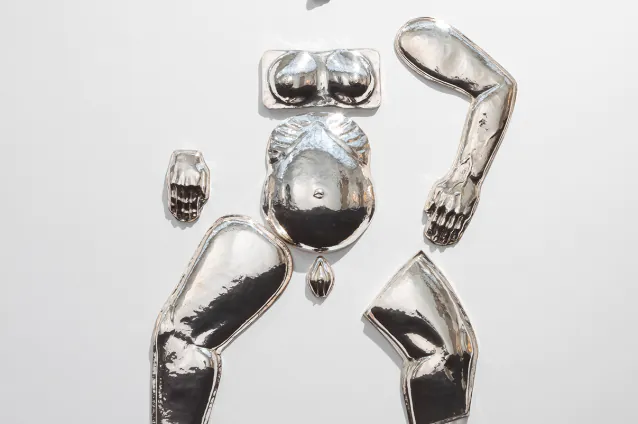

When you look at Prune Nourry’s work as a whole, you are struck by the central presence of the human body, specifically the female body. It opens with the question of producing children (Les Bébés Domestiques, 2007, and Procreative Dinner, 2009), develops with the place of girls in society (the Holy Daughters in India in 2010–2012, and the Terracotta Daughters in China in 2014–2015), moves on to explore the themes of the breasts (Catharsis, 2019, Prothèses de l’âme, 2019, L’Amazone Érogène, 2021) and the pregnant body enveloping everything else, in the monumental Mater Earth (2022). Nourry’s work does not set out to represent female corporeality, still less to glorify it, but rather to show its simultaneously existential and social dimensions, by creating a sense of the solid materiality as well as the consubstantial vulnerability of a woman’s body. Having long reflected on the subject of corporeality in my own essays, and having endeavoured to explore the notion in literary form in my first novel, I was immediately struck by Prune’s way of making our bodies the site of an artistic exploration, where the private and the political are closely intertwined. I saw in this work another way of revealing the corporeal objectification of women; another way, also, of asserting a freely experienced possession of our bodies. Prune, to whom I put some of thoughts her work brings to my mind, considered these with generosity, not always agreeing with them but willing to examine her work in the light of feminist thinking today. And so together, we explored this artist’s work, which centers on the singularity of each embodied existence, to reveal its human resonance, and its being part of a whole.

Camille Froidevaux-Metterie – Recently, you said this: “Cancer took me back inside my own body. It came and reminded me that an artist is never objective. It’s as if I’d sculpted the tumour inside myself as a means to reconnect with my body.” I can see a kind of paradox in that: the female body is at the heart of your work, yet here you are saying all of a sudden that your own body had been hidden. I was wondering how, with hindsight, you were envisaging this process of allowing your own body to join those others that have been portrayed in the light of disease, that moment when you brought your corporeal intimacy into your work as an artist.

Prune Nourry – For many years I worked in the manner of an anthropologist, starting from the universal as a way of connecting with myself. While other artists, like Sophie Calle for example, start from particular aspects of their story to explore a universal dimension, for me it was really the universal that I was appropriating, digesting, be it in Holy Daughters in India or in Terracotta Daughters in China. Then I got sick and I felt the need, in order to get through the disease and give it meaning, to turn the camera on myself. Whereas before I would point the camera toward the outside and hide behind it to film other people’s reaction to my sculptures, I made my film, Serendipity, by turning it on myself. My cancer was like a kind of rite of passage, a rite of passage to my femininity. As a child, I was a real tomboy, making my protests: I felt it was unfair being a girl, unfair to be woman, because in many respects it’s harder. What I was missing in my work was that letting-go in relation to one’s femininity, the acceptance, the embracing of femininity rather than seeing it as something hard. I think the cancer helped me embrace my femininity.

CFM – It’s also as if you were entering the circle of women. It seemed to me that through the disease you were sharing your own real-life experience with that of other “Amazons”. For me, that made sense, because it is the very nature of the feminist approach to share individual stories, every one unique but that together form a chorus and create a group dynamic.

PN – It was a necessary rite of passage from one world to another, a bit like making my way through a tunnel or a burrow that I had yet to explore. I think it’s also a kind of maturing, a maturity. One of life’s events made me go quicker over something that I’d been holding back. And at the same time I was already completely inside it, but hadn’t dared admit as much. When people asked me if I was a feminist I would immediately reply that the “-ist” in “artist” was enough for me. Being an artist was enough—a woman artist! I didn’t want to be confined: molds are my life; the idea of a matrix appeals to me, but, like any artist, I don’t want to be confined to a mold. People would say to me, “you see, the subject you’re working on is women,” and I’d reply, “what I’m interested in is human selection, and in human selection, there is gender selection!” But in fact I realised that I do always go back to the question of women.

CFM – I was struck by the diversity of your representations of women’s breasts. There are breasts to suit every taste, literally, with the breast cakes in Dîner procréatif, and the Holy Daughters’ small pubescent breast combined with teats udders, monumental breasts (Prothèses de l’âme), a spherical box with a breast-shaped lid (Œil nourricier), and the breast-target in L’Amazone Èrogène. Without setting out to do so, I suspect, you created multiple ways of showing breasts, until the turning point of the disease and beyond. Then you had a mastectomy and chose reconstruction. I wondered if that in itself was another of showing and representing breasts that you wanted to explore.

PN – When I made the sculpture of the Amazon for Catharsis, as a symbolic gesture, I sculpted her two breasts and, during the performance, I took a sculptor’s tool and broke the right breast, which is the one that was removed from me. It was like: I was a sculptor before, then a sculpture in the hands of the doctors, and now I’ve become a sculptor again. I think I went for the idea of reconstruction because as a sculptor, I am interested in the idea of material, volume, three dimensions. For me, it was really a form of sculpture, of construction and complete reconstruction.

I was a sculptor before,

then a sculpture in the hands of the doctors,

and now I’ve become a sculptor again.

CFM – Was it your pregnancy that prompted you to begin working on the pregnant body?

PN – No, because as a woman artist, creation and procreation have always been closely connected for me. Hence the term Dîner procréatif, one of my first works and performances. In that respect, pro-action, procreation, and creation are closely related. Pro-action, because you can have an idea, but if you don’t implement it, nothing will happen. The idea has to be realized to be real, to be strong, the process is as much a part of the work as the idea.

CFM – There is an aspect of your work that I find very interesting: the continuous tension in it. There is never anything unequivocal in your works, and the ideas are often developed in couples. The way you show bodies, for example: they are either entirely in pieces, made up of body fragments, as in La Femme Miracle, or, on the contrary, they are whole, full-scale bodies, as in the Terracotta Daughters, in Prothèses de l’âme, or in that astonishing 2007 work, Autoportrait en position de fœtus. I wonder about this tension between completeness and fragmentation. Do you show complete bodies to repair those you split up previously? Or are they just different ways of showing bodies?

PN – The only fragmented work I made before my illness was my friend in a bath of milk which inspired Mater Earth. I inflated a plastic pool and warmed milk on a gas stove, and then immersed my very sculptural friend in it. After the cancer, I began the series Catharsis, inspired by the ex-votos that exist in many different cultures, in Greece, Mexico, Brazil, Italy and elsewhere. I found it interesting to look at those ritual objects, at those body parts. For me, it was a reflection of the feeling I had during my illness, a feeling like I was a fragmented body. People tell you to go see this or that specialist, so you consult a breast specialist, except in reality your body is a whole. That is something that goes without saying in oriental cultures and traditional medicines, particularly Chinese, Korean, or Japanese, where they touch a part of the foot or the ear to heal another part of the body. I am very aware of the fact that the body is a whole, but the body is also a soul, and you can have scars on your soul, and trauma can trigger an illness or express itself on the body. For me, these sculptures speak of that, of the fragmented body, of medicine that separates and divides, of our forgetting that the body is a whole, body and soul are one.

CFM – That ties in with what I discuss in Un corps à soi when I say that we are our bodies. Stating that fact is a way of removing ourselves from patriarchal objectification, of ensuring that our body-as-object becomes our body-as-subject. I believe this endeavor calls for a form of reunification: we need to put an end to the fragmentation of the female body functions, where women are envisaged first and foremost as vulvas and vaginas, because they are first and foremost sexual bodies, later becoming uteruses and breasts, because then they are maternal bodies. To me, in the themes you explore and in everything you say, there is a resonance with today’s feminist dynamic that focuses on the woman’s body in all its dimensions.

PN – Yes, I sense that I am part of that movement, and I sense that it is an essential movement, a necessary movement. I admire the people that, through time, have left their mark and brought about change in a concrete manner, and sometimes even in the shadows. It’s just that I don’t feel the need to shout it out loud, because, as an artist, I’m not sure that I make a difference by saying so. For me, it’s almost a private thing, it’s a bit like asking me what religion I am. I would say “that’s my business!” So, yes, deep down I am a feminist, but as an artist, I don’t think I need to make a statement of it.

CFM – With regard to this taking back of ownership of our intimate bodies, I believe it takes multiple levels of expression and reflexion. In this respect, your work seems to me to be an exploration of these female corporeal themes without making a statement or demonstration, because that is not what art is about.

PN – The thing is, I’m afraid of dogma, I have a deep-seated fear, in my very flesh, of dogma. I am always in doubt, questioning myself, and I want to stay that way, because I think dogma confines people, dogma separates people, it makes you say that what you think is better that what the other person thinks. I think art is about searching, and artists should always be searching, whereas dogma prevents us from searching. That’s why I say that the “-ist” in “artist” isn’t confining, for there is no such thing as artism!

‘Amazone Erogène’, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels (Belgium) until May 9, 2023.

Mater Earth, Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade (France), from March 25, 2023.

Camille Froidevaux-Metterie is a philosopher specializing in feminist history and thought. Her research focuses on themes related to feminine corporeity. She defends an “embodied” feminism that envisages women’s bodies in terms of alienation and emancipation. She is the author of Le corps des femmes. La bataille de l’intime (2018), Seins. En quête d’une libération (2020) and Un corps à soi (2021). In January 2023, she published her first novel, Pleine et douce (Sabine Wespieser Éditeur).