Conversation between Billie Zangewa & Daria de Beauvais

Interview

Conducted by curator Daria de Beauvais, this conversation with Billie Zangewa revisits the origins of the artist’s textile practice, her spiritual visions and commitment, the question of power and the latest developments in her work.

DDB: Let’s begin with the techniques you use, such as sewing – an ancestral, intercultural gesture, traditionally defined as “feminine”. How did you come to it?

BZ: First of all, I think it’s because I’m a very tactile person and I’ve always been, since I was a little girl. Tactility is really an obsession for me.

It also comes from those moments when I was watching my mum and her sewing group in the lounge, and I saw how it impacted their psychology. Some of the women went from being stressed out about their marriages and homes and whatever, and it just became so peaceful and zen; it was almost like meditation. I was a young child so obviously I had no words for it but I knew there was something very important happening in that room and I knew it had something to do with the repetition of stitching and sewing. And maybe the fact of being in a group, although I don’t work that way. I definitely saw something there. I don’t know why but I never asked my mum to teach me to sew. I only started sewing when it was proposed in primary school, I did it with my peers so I guess what I wanted was to be surrounded by girls my age and all of us trying to learn how to do this thing. That’s really where it began and how I ended up coming back to it and using it as my medium of self-expression. It was first about necessity; I had no resources so I had to be quite inventive and creative. Again, it’s also about meditation so it’s a very empowering act for me when I sew – it’s not just stitch in and out, in and out – I’m actually creating my future in a way. I know some people are not spiritual and they don’t believe in projecting desires into the future, but I think that’s where the power lies for me. I believe that I manifest myself through the sewing. Even though I have assistants I always make sure I sew, always make sure I find the time for it as it puts me in a specific state of mind.

DDB: That’s interesting because you started speaking about the sense of being part of – of belonging to – a community, with your mum’s sewing group and you learning with your peers, and then moving on to something very solitary and meditative – more looking inward than outward.

BZ: Exactly, because I am a very introverted person and I do love to be with myself. I can sew when my family or friends are around but it is very important to me to see sewing as an opportunity to find inner clarity. If the whole world could just do craft for an hour every day, I feel like it would be a better world!

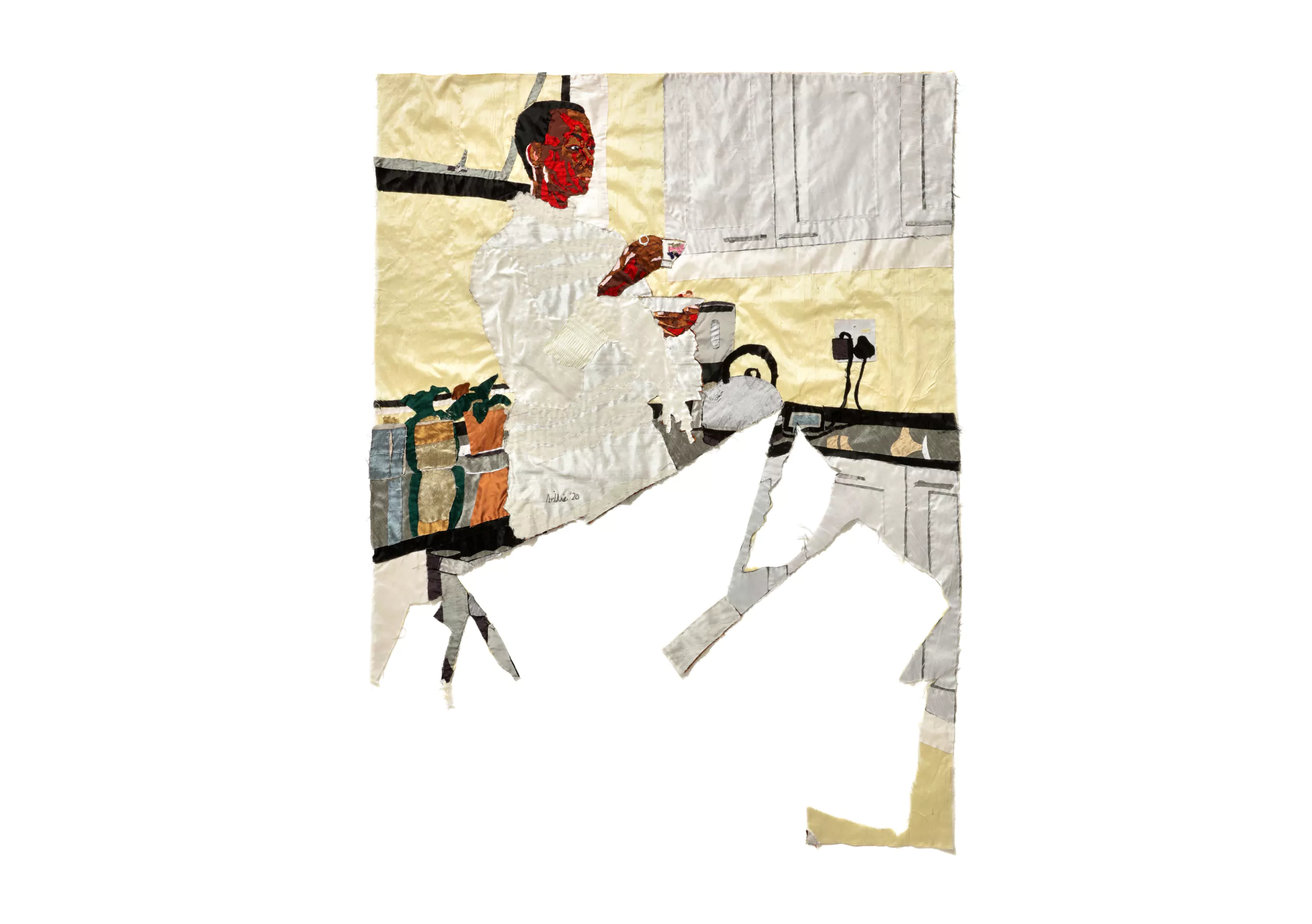

Soldier of Love, 2020. Embroidered silk, 110 × 135 cm – 432/7 × 531/8 in.

DDB: Continuing with your techniques, you have always been working with silk, a material that is both natural and precious. You have mentioned your interest in this fabric for its luminosity and reflective effects – can you tell me more?

BZ: A friend of mine was an interior decorator and I would go with her to collect fabric swatches, to source samples for her clients. I would go home and lay down silk pieces and be very much impressed by their nuances. Depending on where in the weave we place it against the light, it can have the subtlety of paint. I was really, truly moved by this. Also, I had never lived in the city before – I’d lived in suburbia my whole life. And I saw the glass panels on the building surfaces, which reminded me of the silk nuances and reflections. That’s where the connection went for me: the nuanced squares of silk and the glass surfaces of the buildings. That’s what first led me to work on architecture in my creations; it was a jumping-off point. And Then, as I’ve mentioned, I’m obsessed with texture and tactility. And raw silk is just so sexy! Of course, when I started thinking about it, as my process was developing, I realised it was no accident that I stumbled upon silk because it’s a product of transformation, and all I’ve ever been trying to do is transform something within myself into something else. Initially it was about difficult emotions and situations. And at the end I get these beautiful artworks even though it still reveals my pain or fragility, but the joyous moments as well. In a way, what I was seeking was also seeking me. And this is something I like to say, that I was on the path to meet silk because it was how I was going to be expressing myself.

DDB: Your works sometimes appear to have an “unfinished” aspect. Is this a way to let the work’s narrative to continue?

BZ: It is first about bringing us back to the medium because if it was all perfect it would look like a canvas, that’s why I make it more textured. It also speaks to the perfect and the imperfect, as I like to call it. I believe all of us have got wounds and scars, but society always wants us to project ourselves as perfect while it is the imperfect that makes us perfect. What I’m saying is that I am showing my vulnerability, my traumas – I’m showing the negative side of who I am but at the same time I’m celebrating. I believe that when we hide those damaged parts of ourselves, we create shame and shame is the most toxic emotion, an incredibly destructive feeling. The important thing is to be able to reclaim it, to feel ‘I’m beautiful because of it and I’m beautiful in spite of it’. That’s why I like the rough edges – as I said, it’s both the perfect and the imperfect.

DDB: Following up on what you said, the missing fragments in your works could also be described as tearing apart, bringing forth a form of violence that contradicts the scenes of peaceful everyday life that are mostly depicted.

BZ: Yes, because life is not easy. Even the way we come into the world is violent, both for mother and child. It’s a traumatic event, but it bears this beautiful fruit. I feel that’s the contradiction of nature we all have to live with. That there is violence and trauma, but there’s also beauty and peace and gentleness. I’m really embracing all of that.

Portrait of the Artist in Springtime (Detail), 2022. Embroidered silk, 57 × 55 cm – 223/7 × 212/3 in.

DDB: Indeed, love and a sense of peace both shine through a lot of your works, while the torn elements tell a different story, maybe something darker?

BZ: It’s also a way of allowing a kind of interaction between myself and the viewer, where the viewer can finish the narrative. And there is as well a communication between my works: a missing part of one work can be a component of another one. But I love the idea of entropy, and I know we’re going to this darker aspect, where things break down. It’s open to interpretation, I think it’s up to the viewers to decide what it means to them.

DDB: When I see your work, I think about this famous sentence: ‘the personal is political’, which appeared at the time of the second wave of feminism in the 1960s. It seems particularly relevant to your practice.

BZ: It makes sense for me in that I find so much meaning in the most mundane things, and elevating those mundane things does kind of politicise them. It’s very exciting that I get obsessed with mundane things and they mean something when they’re exhibited or published. That’s really exciting because it’s just a reflection of who I am. I’m not a grand gesture person, I’m not waiting for some big movement to happen in the world for me to make art about. I am interested in fleeting moments and just taking the time to appreciate them as a lot of artists do, I believe.

DDB: Saying that you’re not a grand gesture person shows that you are grounded in your work and your position as an artist. Important works are not necessarily grand gestures; humble works can be very strong, political, and meaningful. Your work seems tightly woven between the general and the particular, society and personal life, History and stories. How do you manage to position yourself on the threshold of these different strains?

BZ: I think that I just have to be authentic. I’ve had lots of different jobs in my life before I really decided to be an artist, knowing this decision would challenge me for the rest of my life. I knew I had to be authentic in sharing my experiences, so couldn’t do work about Apartheid in South Africa or preindependent Malawi for instance, because those are not my experiences. That’s how I started to focus on the personal. This is the one area in which I can be truly authentic. Even if the subconscious mind is a tricky space and we don’t always really know ourselves fully…

DDB: There’s also a double axis between the representation of the interior, the intimate, and that of the street, the public space. In both cases, we are dealing with representations of moments that may seem insignificant, but which carry within them much more than that. I understand when you say you are not a political artist, but again, the personal is political and I think the mundane moments you represent can be the seeds of possible revolutions.

BZ: I think that sharing is powerful. If you share with somebody who feels unseen and alone, and you show them that you have those moments too, suddenly they’re not alone anymore, they feel empowered. Also, maybe by highlighting very ordinary things there is a sense of affirmation.

La Tour, Ponte City, 2004. Embroidered silk, 71 × 50 cm — 28 × 19 in.

DDB: On another note, architecture and public space have been for a long time been considered as masculine, while domestic space was a prison or refuge for women. But this historical “evidence” is not inevitable, as your work shows beautifully, going from urban landscapes to interior scenes. It’s about putting women at the centre of a story from which they have been absent for too long.

BZ: Yes, exactly! Because nobody ever wanted to go into the homes and see what women were doing. For me, having a child did highlight the domestic space because I had to be in it, even though I had always been a homebody, in this particular instance there was a very strong reason why. That’s really what opened my eyes to all the things that people staying home were doing but no one was acknowledging or seeing. And understanding also that the domestic landscape is a very challenging one, that there are so many things that you have to deal with.

DDB: I’m impressed by your ability to use personal stories to tackle social issues that shape the status of women, like the question of intimacy. You reveal things that are usually left unsaid, and reveal their relationship with the world, deciding by yourself what your role in the world is and what you want to do with it.

BZ: Life can be so beautiful if you’re given the opportunity to find your path, when you follow the signs. I remember something I did when I was about five years old and we were still living in Malawi: women and children were supposed to welcome visitors, especially men, by kneeling down and greeting them with one hand on your elbow, then with the other hand, in a submissive gesture. I was watching this and thinking: ‘How come the men don’t have to do it? Why is it always the women and the children?’ So, I spoke to my dad one day and said: ‘Daddy, I don’t understand why the women and children have to kneel, and the men don’t. I don’t know how you’re going to take this, but I’m never kneeling for anyone again. If it means that I’m not allowed to greet guests when they arrive at the house that’s fine, but you cannot change my mind.’ I was very lucky because he supported my decision, when he could have decided otherwise. He was like ‘I’ve got a fierce female for a child and she’s questioning conventions.’ So that was the breeding ground.

DDB: To conclude, we could say that your work is about emancipation. Behind the apparently innocuous scenes that you create, there is a strong will asserting itself.

_

‘Billie Zangewa: Field of Dreams’ SITE Santa Fe, USA, November 17, 2023 — February 12, 2024.

‘Billie Zangewa, A Quiet Fire’ Tramway, Glasgow, Scotland, until January 28, 2024.

DARIA DE BEAUVAIS is Senior Curator at the Palais de Tokyo (Paris), independent curator and writer. She has curated or co-curated numerous exhibitions, both solo and group shows (including the 15th Lyon Biennale in 2019 and “Reclaim the Earth” in 2022). She teaches “Exhibition Practice” at the Panthéon-Sorbonne University and is co-head with Morgan Labar of the research seminar “Indigeneity, Hybridity, Anthropophagy” at the École normale supérieure. Her experience has included roles in institutions and galleries in France, Italy and the US.