Zamok & Fatrasies

Essay

Zamok & Fatrasies

The unsuspected origins and past of Orsten Groom’s paintings.

By Jean-Michel Geneste

The work of Orsten Groom, are for many reasons traceable to the first Paleolithic artists – masters of cave painting and drawing.

Here is a figurative painter who can claim descendance from Chauvet and Lascaux.

Like a dizzying rush to the head, images of decorated grottos assail me, flowing into every corner of my mind, as the consequence of years of studying the graphic expressions preserved on their walls.

What do I see that connects these two types of works in such a fertile manner?

Painting reveals figures which do not directly originate from our current world.

Elements of history and recalled memory confront us with the singular destiny of the painter.

Bearing titles whose meaning is often hermetically distorted, those compositions weave the output of an artistic and historic reflection which triggers knowledge and images that have been widely shared.

Such is the case of the CHROME DINETTE series whose transhistoric theme, taking in Moses and Sigmund Freud, recapitulates 5000 years of history.

Several hundred thousand years ago, speech and language made a determinative intervention in human history by providing the basis for the social sharing of knowledge.

In doing so, language became the cement of sociability among humans.

As the expression of language, speech carried the decisive progress of the dematerialization of the object.

Through its being named, replaced with a word-sound in the physical world, the object was signified by a symbol.

From that moment on, the object was presented with a symbolic life in the human thought and work process.

Following the gentle evolution and perfection of languages, the world’s objects gradually found their place in the linguistic forest of symbols.

As symbolic thought matured, a universe parallel to reality grew ever more consistent.

Approximately 50,000 years ago, Homo sapiens invented figurative art.

In other words, every human from then on was capable of giving a horse a coloured hide, shiny hooves, and a flowing mane floating in the wind, without needing to resort to speech, words, long descriptive sentences, the lamentations of language – in order to connect what they saw with an evocation requiring nouns.

Limbe

The appearance of graphic representation alongside language immediately transformed human communications.

From the moment it emerged, all of its expressive possibilities began to be tested, invented, and developed to a high level of ‘representational know-how’.

With representation, specific skills holding astounding potential spontaneously appeared.

The graphic techniques gave form to the first drawings, engravings, and paintings on the walls of caves and on bones.

These first representations, initially discovered in the middle of the 19th century, fed our dreams of prehistoric man.

For modern viewers they established the shapes of the mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros and the cave bears, lost creatures of the Stone Age.

They also showed us the faces, hairstyles, and attitudes, of women, men, and children we never saw.

Such rare and precious animal and human representations shaped our imagination.

Long before I encountered Orsten Groom, I had got to know these periods and familiarized myself with the techniques, material culture, and figurative work of our very distant Paleolithic ancestors: those ‘others’ from somewhere else and somewhere before; people so different from us who invented the first figurative art.

This art, reaching out to us from the depths of time, has the power to affect us without depending on our knowledge of any kind of reference and as such retains a great deal of mystery.

We can produce endless commentary on the subject but only careful study allows us to connect with it. Unfortunately, we are still afraid of the silence around it: a silence of powerful ancestral figures.

‘Painting is mute,’ Maurice Merleau-Ponty resolutely stated.

DZIEDZINA

Early on, these formal achievements struck me as already accomplished by contemporary artistic standards, even though they were barely emerging.

Confronted with them, I felt the need, in order to apprehend them, to pay particular attention to the materiality of these works, to their techniques, which were primitive in the sens of being uniquely the product of original inspiration.

Forms of expression which we would today refer to as ‘artistic’ were then regularly invented, forgotten, then reinvented, as at the time areas inhabited by humans were sparsely populated. There was less of a guarantee of frequent or thorough communication, or even any communication at all.

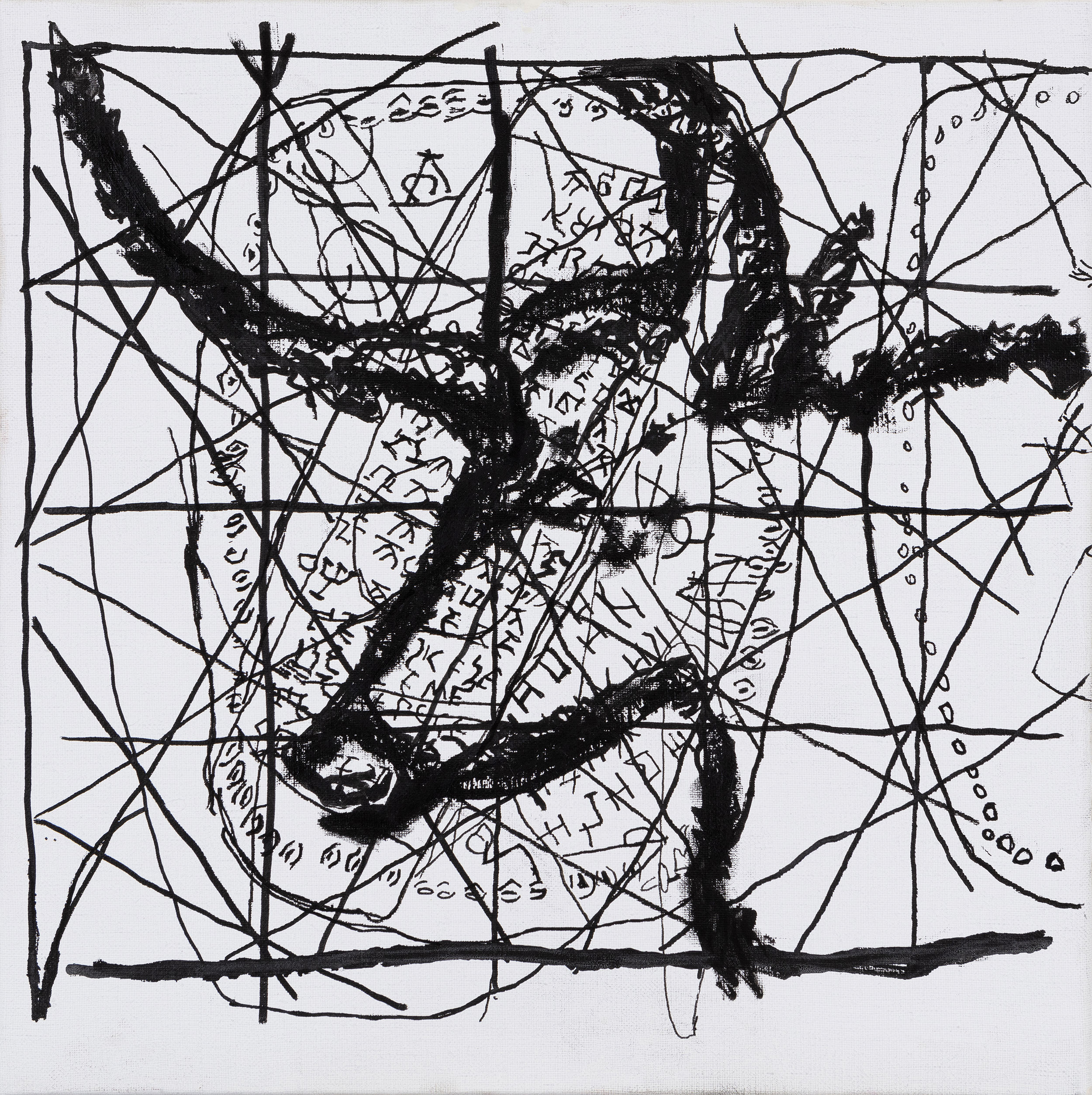

There is another reason, moreover, why Orsten Groom’s painting shares a common ground with Paleolithic cave art. The compositions, spread as though across a wall, are roamed with a multitude of forms which arise from the principle of superposition. They preserve the traces of the stages of completion accompanying the painter’s thoughts.

“The dedicated french word for this intertwined tracery reasoning, fatras (which hardly translates as “jumble”) also designates an utter specific form of medieval poetry, screesing seemingly nonsensical and bawdy mishmashes that convey highly elaborated cryptic historical parodies – under the name of Fatrasies.”

The dedicated french word for this intertwined tracery reasoning, Fatras (which hardly translates as ‘jumble’) also designates an utter specific form of medieval poetry, screesing seemingly nonsensical and bawdy mishmashes that convey highly elaborated cryptic historical parodies under the name of Fatrasies.

This Fatrasic gesture here particularly underlines the German Hegelian concept of Aufhebung, which casts what is outdated as internalized, metabolized in its very process. History in the sense of progress is then neutralized.

This cryptic (as in a crypt) pictorial and poetic technique is primordial of Orsten Groom’s formal reasoning who summons on root figures, then transforms, conceals and reveals patterns through a – sometimes substantially thick – coat of paint.

These inexhaustible superpositions which elaborate the final overlapse are also evident on the engraving-filled limestone walls of the decorated grottoes, as in the Apse at Lascaux, where thousands of animal figures have been overlaid for millennia.

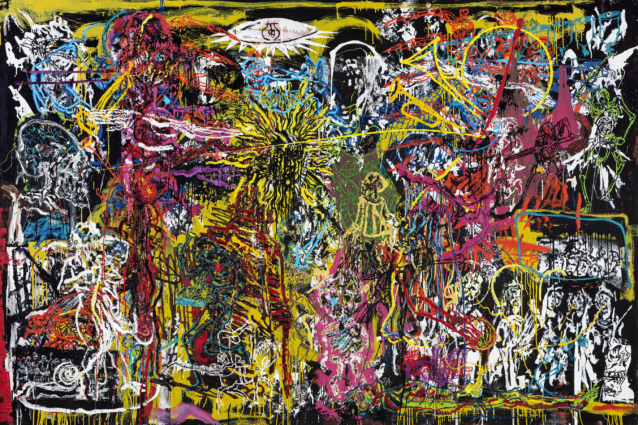

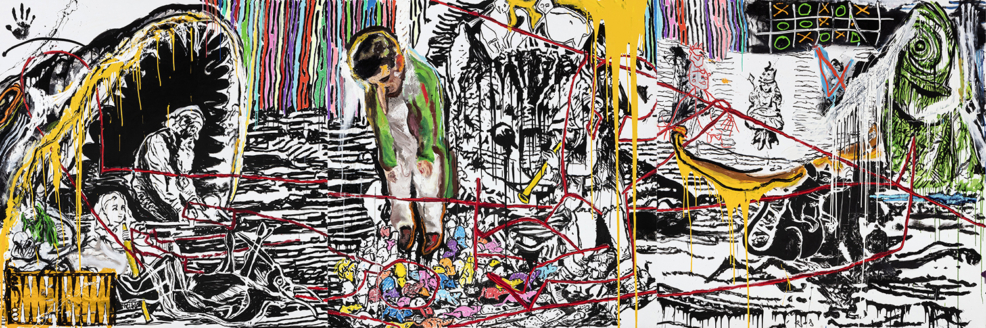

All of Orsten Groom’s large-canvas parabolic paintings are highly structured and feature countless partially visible figures in the midst of an abundance of vivid colourful markings. They are parchments to be deciphered, which invalidate any possible narrative interpretations as in STENTOR or EXOPULITAÏ.

Thus, although their titles (even names, or ‘Zamoks’ as Orsten Groom puts it, meaning both Castle and Padlock in eastern languages) concentrate their cryptic meaning as in an egg or a map of the forgotten often streaming down rogue etymology channels.

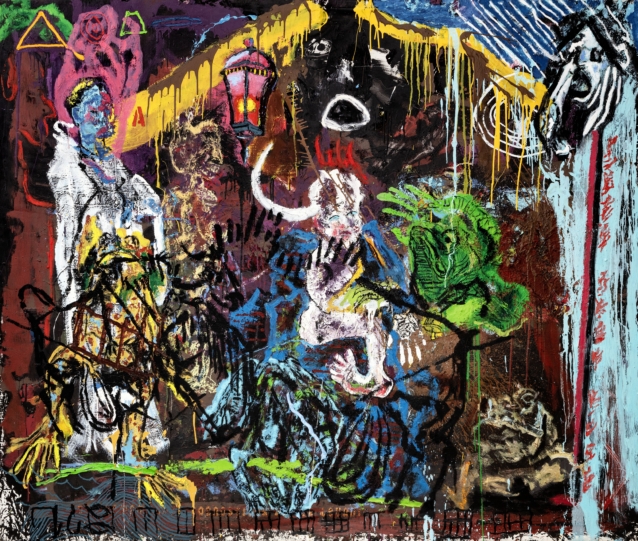

Even more obvious are the paintings inspired by motifs directly taken from Paleolithic art, if we can even identify them amidst the fatras of forms, to borrow a ‘trademark’ term dear to the painter. This is also visible in the images which inspire his wide triptych dedicated to the imagery of childhood, LIMBE (‘Limbo’ meaning ‘threshold,’ ‘border,’ ‘edge’), which evokes a wealth of Eurasian traditional mythical and religious stories. In Orsten Groom’s paintings, figures summoned by the deco- rated grottos are greater in number than we initially realize. Some are vigorously deducted as is the case with The Large Black Bull from Lascaux, which confronts the golden yellow surface of DIEZDINA. In the ODRADEK series, inspired by Kafka’s text, the figures, whose linear contours are so precisely drawn, originate from the markings of Southwestern France.

EXOPULITAÏ

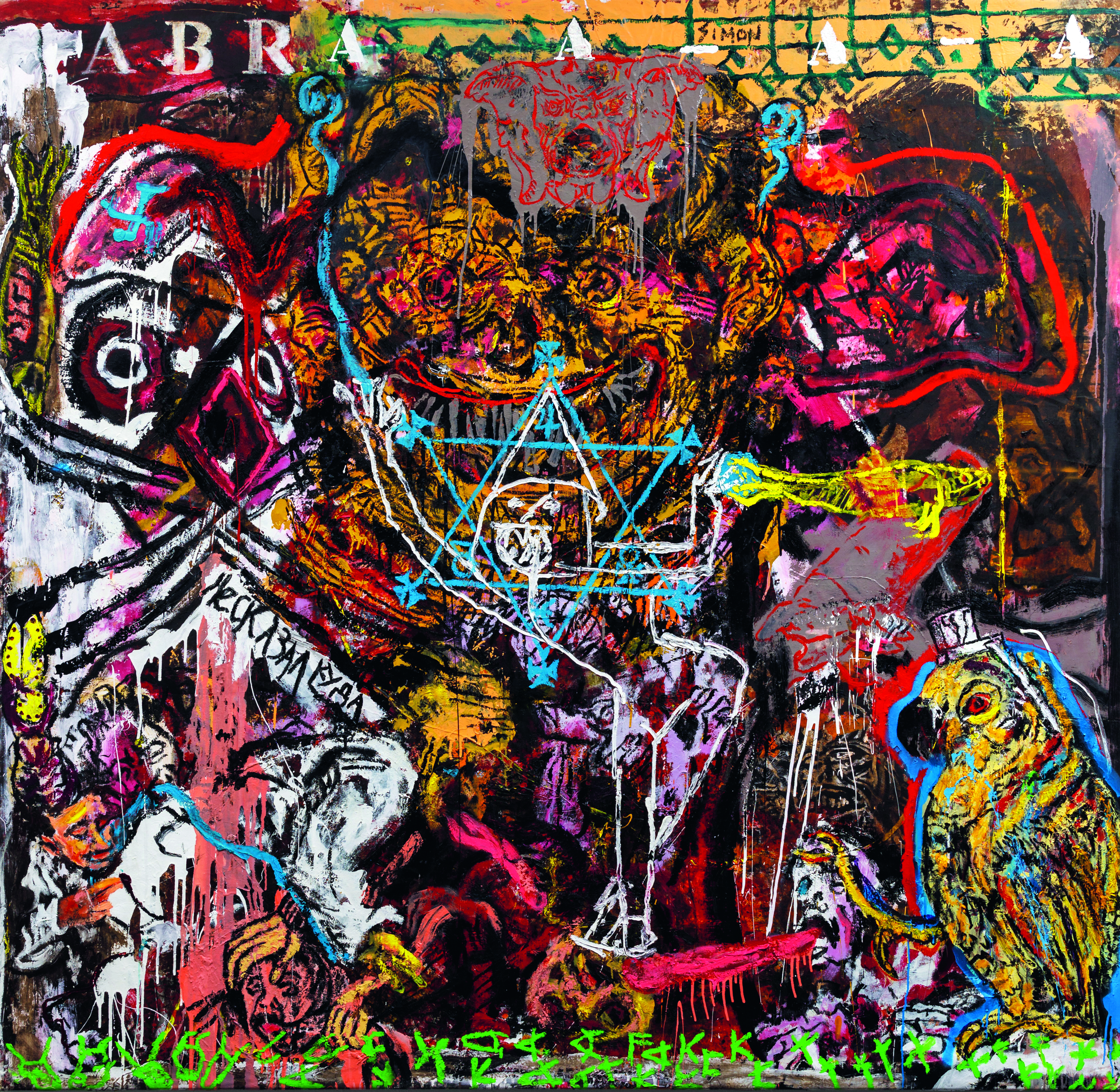

In FORTSCHRITT IN DER PAPAGEISTIGKEIT, at the centre of an extravagant composition dominated by representations of winged Egyptian gods, a magnificent blue and yellow Ara macaw conspicuously stamped with a star of David, and small characters with Hitler faces, one makes out the anthropomorphic, half human-half animal, black silhouette of the famous Sorcerer from the Trois-Frères grotto in Ariège. In HEPHARCHERON, we notice, among other details, light-colored vertical human shapes and an imposing animal face in black. It is only upon a second glance that we are able to see what is represented across the network of thickly daubed curved lines providing the painting its tonality: the first prehistoric representation of a confrontation between animal and human. The canvas skillfully evokes the thick and grainy black manganese pigment used to paint the 23,000 year-old Scène du puits (Shaft scene) discovered at the bottom of a joint at Lascaux.

“This cryptic (as in a crypt) pictorial and poetic technique is primordial of Orsten Groom’s formal reasoning who summons on root figures, then transforms, conceals and reveals patterns through a – sometimes substantially thick – coat of paint.”

When Simon Leibovitz doesn’t dream of Paleolithic art or paint, he draws. When he lacks the materials, for instance while travelling, to illuminate the stars in the eyes of his little boy, he sketches out magisterial forms whose contours would astonish even the masters of Lascaux or Altamira. Reaching an important stage on his emotional journey, the painter has become a father, and henceforth, his painting takes on childhood, as a nodal theme, original in the historical sense.

That, as Rilke once wrote “rewinds up all that ever was infancy”, an ancestor older than all we ever were. This view establishes a subtle and fundamental filiation between infancy of man, and that of painting. Merleau Ponty (him again) wrote in 1950 the Prose of the world : “Each new painting takes place in a world inaugura- ted by the first one; it fulfills the wish from the past.”

In 2022, this primordial place of childhood as pre-history in painting led the theme of an exhibition in Cannes’s former morgues. The published book LIMBE [Le Vroi dans la Nuit], revealed the strands of thought of the painter in his time, wondering which is the most infant between the paleo (the oldest, the ancestral), and the neo: the newborn. What happens when the twain face each other ?

The 2024 VOLCAN DU COMA retrospective, on the other hand, retraces this intimate pictorial trajectory through the standpoint of an amnesiac event of his personal past.

Ancient and recent works set altogether a storm at the Sète Paul Valéry museum, a place which itself is subject to marine turbulences and favors transformations, as marine borders, celestial limbs, strands and waterways are believed to in Amerindian cultures.

Painting such as these emanates from the origin flow of a timeless world.

Jean-Michel Geneste is a Paleolithic archeologist and emeritus general heritage curator. A former Director of Research at the Lascaux cave, Jean-Michel Geneste has devoted himself to the archeological study of decorated caves. He directed the multidisciplinary study program for the Chauvet-Pont d’Arc cave until 2018, while simultaneously coordinating archeological research programs in France, Russia, Ukraine, South Africa, Papua New Guinea, Canada and Arnhem Land. He has edited books on the Paleolithic era and rock art, published numerous articles and, most recently, the book Prehistory. New frontiers. [Préhistoire. Nouvelles Frontières] (Geneste, Grosos, Valentin, Éditions de la MSH, 2023). He is also committed to the mediation of prehistory through audiovisual and new technologies.

Born in 1982 in Guyana, Orsten Groom is a multidisciplinary artist of Russian-Polish origins. At the age of 20, he suffered an aneurysm which left him amnesic and epileptic. During his convalescence he learned that he was a studying painter at the Beaux-arts of Paris, returned to art school and embraced a renewed vocation for painting as recapitulation of out of self’s entire world memory.

From that moment on, he positioned himself as a fiercely independent artist, developing a protean body of work that reaches beyond painting to embrace music, sculpture, film and poetry.

In December of 2023, the Sète Paul Valéry museum presented the retrospective VOLCAN DU COMA