Fossil Light, Explosive Matter

Conversation

Between July and November 2023, anthropologist Tim Ingold and artist Abdelkader Benchamma corresponded and exchanged ideas on themes dear to both of them. This conversation, involving chaos, the universe, fossils, and strata, as well as creation, introspection, and freedom, is here reproduced in full.

Fossil Light, Explosive Matter

Tim Ingold and Abdelkader Benchamma

Abdelkader Benchamma – ‘It was like seeing the face of God,’ exclaimed George Smoot, lead cosmologist on the NASA COBE (Cosmic Background Explorer) Satellite project, when announcing the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation.

Fluctuation and radiation. Visible traces in the cosmic background. Traces of a universe of beginnings which, nonetheless, no longer exist. As though radiation could leave the imprint of a trace, lines, a substrate.

All these strata which have fascinated and inhabited my drawings for some years now are as much geological layers as traces left by sediment on walls, by tenuous and fragile forces which nonetheless repeat a specific current, a specific fluid, over centuries to finally succeed in modifying matter. The instantaneous image of a flux which no longer exists, which cannot be resolved by disappearing after numerous processes of decantation.

Or else these superimpositions of sediments are part of a fabulous and infinitely large brain, gathering the rumours and beliefs which have followed one after the other, transforming and adapting to technological progress since the dawn of humanity. Repetitions, premonitions, and anticipations. Places and moments where neither the future nor the past exist. Scenes appear on these strata – which hold fossils of fossils – some scenes have already evaporated, while others display the precision of a memory which can never be wiped away.

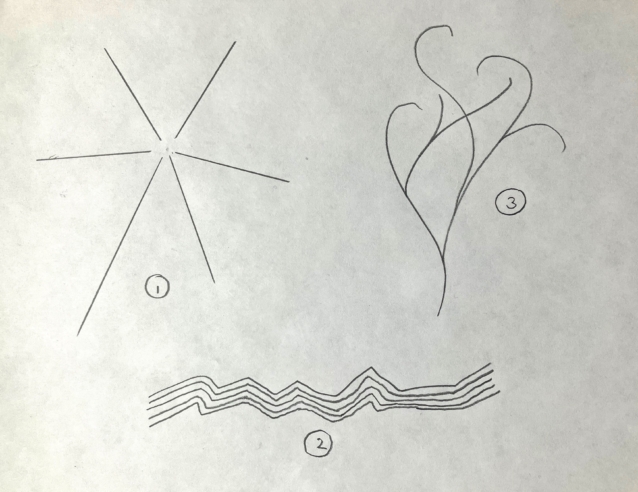

Tim Ingold – What fascinates me in your work is the play of light and darkness, of black and white, of traces and surfaces, of radiation and flamboyance. It is full of lines, but they are of different kinds. There are straight lines radiating from a center, which make me think of rays of light bursting from an explosive source like the sun, or a distant star. There are parallel lines that remind me of the ancient, folded sediments of a rock face. And there are lines that twist and curl like flames in the wind. I have drawn them in Figure 1. I’m interested in what these lines do, and in the relation between them.

The straight lines could be a radiant sunburst; the parallel lines could be the strata of a fossil-bearing, geological deposit. Let me begin with these two kinds of line. I will turn to the third – the twisty, curly line – in a moment. Placing the first side by side two leads me to ask a strange question: certainly not one that I had ever thought of asking myself before. But you have already asked it in the title of your book, ‘Fossilized Ray’ (Rayon fossile, Actes Sud, Paris 2021). How, I wonder, can a ray of light become a fossil? At first glance they seem like complete opposites: the ray instantaneous, immaterial, a fount of renewal; the fossil permanent, rock solid, a relic of antiquity. One is light and weightless; the other heavy and dark. With one, the world bursts into life, with the other it is encrusted in death.

Three kinds of line: (1) radiant lines; (2) parallel lines; (3) curling

Yet the fossil is not just any rock. It is the petrified residue of a thing that once lived, grew, and breathed. From where, then, did it get the energy to do so? From the sun, of course! Perhaps we could imagine life – or even define life – as a process that converts solar radiation into fossil material. Wherever anything lives and grows, the process is going on. The living tree, for example, sending out its leaves to catch the sunlight, is on its way to becoming part of a seam of coal. The white light of the sun is turned, by way of the tree, into charcoal-black matter. And between the whiteness of light and the blackness of matter lie all the colours of nature that we are accustomed to see by daylight.

But what is this light? And what is this matter? It is not light, or matter, as the physicists or cosmologists at NASA would understand it. In the science of optics, light is defined as radiant energy, coming in a range of wavelengths to which photoreceptors in the eyes of humans or other creatures are primed to respond. These wavelengths give us the different shades of the spectrum. White light, then, is what you get when all these shades are rolled together.

But this is not the light that bursts through the clouds on a summer’s day, and causes all on which it falls to shimmer. The sunburst and the shimmer are phenomena of experience, ignited in the meeting of mind and world, rather than physical events to be objectively measured and recorded. Beings of every kind, humans included, are born into this light, into an ocean of illumination. As William James wrote, in his Psychology of 1892, ‘the first time we see light, we are it rather than see it’.[1]

Even the tree, if its leaves could see, would emerge as a creature of the light, drawing down the sensation of every eye-leaf into the luminous beam of its trunk. Where to us the trunk might appear solid, branching out into its canopy of leaves, in the tree’s vision it would open to a world on fire, with every trunk, branch and leaf ablaze in a forest of flames. [2] The ray and the flame, however, are not the same. Rays that pierce the summer clouds and cast shadows on the ground are straight. But rising flames, like the trunks and branches of trees, twist and curl in response to aerial fluxes in the atmosphere. So that’s where the third kind of line comes in, the one that twists and curls. This line is not of radiation but of flamboyance – a distinction familiar to the builders of Gothic cathedrals, for whom rayonnant and flamboyant stood for distinctive architectural styles. In one, straight lines – for example in the tracery of windows – would radiate from a center; in the other they would twist and curl like arboreal foliage.

Yet a life that begins in the white heat of light inevitably ends in the darkness of matter. As with light, this is not the matter of physics, with its atoms and molecules differentially excited by electromagnetic radiation. It is rather the matter of geology, of a planetary crust rent by tectonic forces of colossal magnitude. You can witness it, for example, at the cliff face, where the sea has cut through layers of sedimentary rock. Deposited over the ages like seams of coal, these layers show up as a series of parallel fossil-bearing strata, albeit creased, contorted, and fractured in such a way as to remove any trace of regularity. And you can witness it, too, in your drawings. On the cliff face as in your drawings, the remarkable thing is that despite all their irregularity, the perfect parallelism of the strata is preserved.

“All these strata which have fascinated and inhabited my drawings for some years now are as much geological layers as traces left by sediment on walls, by tenuous and fragile forces which nonetheless repeat a specific current, a specific fluid, over centuries to finally succeed in modifying matter.”

Abdelkader Benchamma

This is by no means the only example of parallel lines in nature, however. If you turn your back to the cliff to face the sea, then you will immediately see another series, this time of waves advancing towards the shore. They, too, continue to march in parallel despite the irregularity of the coastline around which they bend. And on the ebb tide, you can sometimes see parallel corrugations in the sand, or lines of weed, left by the waves on their retreat. Now look closely at the shells that the tide has thrown up on the shore, and you will find that they, too, are streaked with bands. These are formed as the shell grows, in increments, adding layer after layer of material. And one day, those same shells will become fossils in a rocky stratum. It seems that whereas light radiates, matter is everywhere slave to the parallel line!

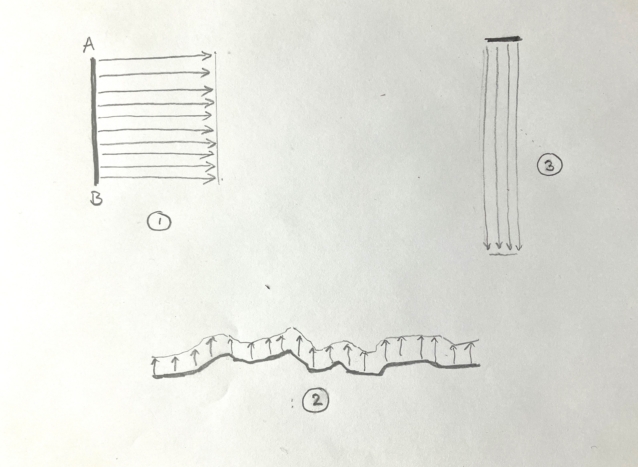

In every case, the parallelism comes from the simultaneous displacement of a line, along its entire length, in a direction at right angles to its longitudinal extension. The word for this is offsetting. Waves, for example, run parallel to the shoreline, but are offset towards it. The striations of sedimentary rock are at right angles to the axis of deposition. The painter Paul Klee, in his notebooks, explained how the offsetting of a line A-B itself produces a plane surface.[3] If the line is offset by a distance equal to its length, then the result is a square. For Klee the square is a figure without any accent or emphasis of its own. Squares tend to arise in human acts of enframing, which turn those portions of the world enclosed within them into their own pictures, enforcing a division, which was not there beforehand, between representation and reality. When I see squares in your drawings, this is also what they seem to do.

The living world, however, always overflows any frame you try to put around it, just like it overflows the squares in your drawings. That’s why, despite the proliferation of parallel lines in nature, squares are almost impossible to find. Instead, one of two things can happen. Either the line to be offset is very long compared with the distance of offsetting. This is what occurs with waves and rock strata. A stratum or a wave-crest can carry on seemingly forever, even if the distance between successive strata, or between successive crests, remains short. Alternatively, the distance of offsetting is very long compared with the length of the line. Think of the cascading waterfall, of a depth much greater than its width. Either way, what is generated is not a square but something more like a ribbon. In Figure 2, I have tried to draw these alternatives.

Three kinds of offsetting: (1) the square (after Klee); (2) the wave crest; (3) the waterfall

Another place where you find parallel lines, in an explicit mimesis of nature, is in the Japanese zen garden, surfaced with loose gravel. These lines are generated, with the utmost care and devotion, by drawing a rake through the gravel. This is like the waterfall: a short line, already built into the structure of the rake, is offset over a very long, and potentially infinite distance. Yet paradoxically, gardeners themselves would compare the lines produced in this way with the ripples of a stream or lake, or even the waves of the sea. The paradox lies in the fact that ripples and waves are in fact produced by the movement of wind across the surface of the water. And that movement is transverse to the lines of the ripples or waves it induces. In terms of my figure, an offsetting of type 3, produced by the draw of the rake, is imagined as one of type 2, produced by the breath of the wind.

Raking, thus, can create the appearance of a surface ruffled by the wind, but is unable to imitate the action of the wind itself. Isn’t it the same with your drawing? Like raking, drawing leaves the trace of your gesture in the surface. The movement goes along the lines. Yet when we observe the finished work, with all its parallel striations, our eyes don’t want to follow the lines along their length, recapitulating your movement in making them. Rather, they want to go across, following the offset as if they were observing waves advancing on the shore, or the sequence of strata in a geological formation. And in doing so they enter into a different register of time: not the time of your drawing, but the time of the earth, of the universe itself, in the tumult of its unfolding.

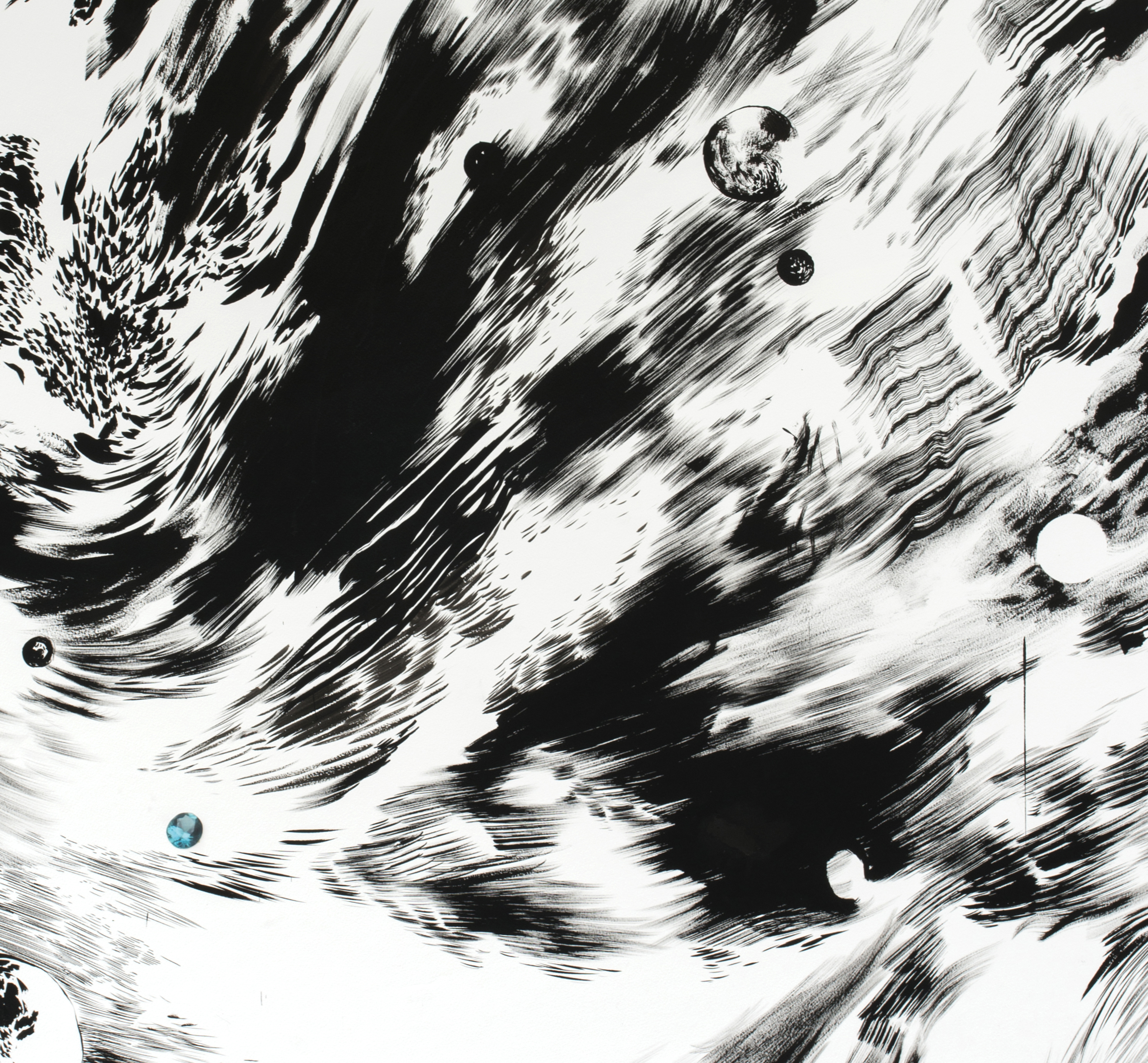

This is not, of course, to deny that you can draw like the wind. But such drawing produces lines of a very different kind. They swirl about, like the air we breathe, like flames and smoke. These are the flamboyant lines – lines of the third kind. There are lots of these in your drawings too, alongside the spiky rays and parallel striations. And the world they describe is not neatly partitioned between sky and earth, with the ground beneath and the air above. Perhaps it would be better imagined, like the universe itself, as an explosion of dark matter, in which torn and broken fragments of rock, bearing in their striations a record of their original deposition, float amidst corrugated sands, wind-torn trees and the churning clouds of a stormy sky, all shot through with shafts of sunlight. The end of this universe is no less than its beginning. As in your drawings, it is black rent apart by shafts of white.

Engramme-Archeologie

Abdelkader Benchamma – Before anything, before even picking up a paintbrush, I begin by invoking an image, a piece of mental landscape, sometimes several days or weeks before going into the studio. In this way I live with this shifting mental image, upon which I add and subtract matter and flow.

A silent dialogue thus ensues between the images floating on the surface and those which are unconscious, buried in the layers of my mind.

There are periods of decantation, which cannot be compressed.

I cannot say to which type of living matter these images correspond, yet they seem loaded with history and intensity. These images are inhabited by a sound, or a vibration, a speed, or a flash of light. Recently, reflections of colour have appeared, as though the colours were as mutable as the shapes.

Minuscule landscapes which were fossilized in a matter of seconds as if by a lava flow, and then, the crash of planets we could only ever traverse in dreams; sometimes more figurative, they seem to bear the echoes of long-forgotten rituals. Even in the absence of up or down, the impression of descent is present.

In speaking about dreams, I wish for my landscapes to possess the ambiguity of those encountered in dreams.

I am referring to these strange dreams that we have all had, where we understand upon waking that we’ve visited spaces which seem exceptional and disconcerting in their intensity without being able to put our finger on why. And without understanding why, we must often fight against our mind to preserve them.

A mountain remains a montage in a dream, but sometimes we understand that it is equally a magical space, with its own history and symbols. It is an archetypal mound or a forgotten tomb, a link between the heavens and the depths of the earth, a vain attempt to draw closer to the gods, to the celestial or extraterrestrial – a place in our mind which we circumvent without being able to penetrate.

“The burrows of dreams construct our cities; parallel worlds describe the structure of the world itself, which is not one, which cannot be totalized, but at least split into two, cleaved, leafed through, fantastic.”[4]

Drawing is always a tense dialogue with a blank space which is never entirely empty: it is something which is both appearing and in the process of disappearing.

Drawing as mesh net: as much something tangible and real as something which draws emptiness.

Certain questions do not leave me, in particular the following:

- Can we see something which we do not know?

- And how would we see it?

Since the human brain sees by recognizing forms, how does it react before something which does not correspond to any known form? Pareidolia – the brain function consisting in selecting from our reserve of mental images one form to designate another, almost urgently, often clumsily, and in a disappointingly repetitive manner, like a face in this rock or that cloud – works for a moment. But then what?

“And the first drops of rain came down, and the light changed radically in the preternatural way that’s completely natural, of course, all the electric premonition that rides the sky being a drama of human devising.”[5]

Speaking about the novels of Tabucchi, Clélie Millner writes that ‘traces and imprints are a form of resistance of the past, they must be considered as a new mode of being. It is impossible to speak of the present without taking into account its rip, its impossible linearity, relentlessly called into question by the apparitions of the past.’[6]

We are not speaking here of the infinitely large, but we are still speaking about an absence which cannot allow itself to disappear completely.

It was like seeing the face of God, when it was discovered.

The NASA COBE satellite was the first to locate and map temperature fluctuations in the cosmic background.

“And I believe that what we witness, in your drawings, is this very explosion, detonated by the fusion of the two worlds of cosmos and affect, or better, perhaps, of dreams and waking life. But the birth of the new is also the fracturing of the old, as the explosion rips through the contorted, fossilized beds of ancient sediments.”

Tim Ingold

Tim Ingold – You speak of the birth of a universe which also turns out to be an immense brain. You are inside this brain, but you say you are also in a world of dreams – so then it’s the brain that’s inside you! We’ve all had those dreams in which we feel we are tumbling headlong into a bottomless void. They invariably end in an abrupt awakening, not uncommonly in a panic and a sweat. Perhaps, because there is no gravity in your dream world, there is no up or down. There’s just the wind, which knows neither. You speak thus of a descent that is not so much a drop as a kind of crash landing.

But I want to know: is the world of your dreams distinct from that of your waking life, or is it the same world, taken from a different orientation? Could it be that in the dream, the white figures are on a black background, whereas in waking life it’s the other way around, with the black on a white background? I don’t suppose that when you draw, you are fully asleep. But I wonder, are you either fully awake? Or are you on the threshold between sleep and wakefulness?

To your question – can we see that which we do not already know? – plenty of scholars would answer that we cannot. In their view, seeing anything depends upon the projection of a form – already stored in the human brain, in its memory bank – upon the inchoate mass of visual stimulation registered at the surface of the retina. But I am convinced that they are wrong. First, we must make an important distinction. It is one thing to say ‘I can see this or that’; quite another to exclaim ‘I can see!’ The first is humdrum and unremarkable; the second ecstatic; so let’s get the humdrum bit out of the way first.

I take the view, which I owe to the ecological psychology of James Gibson[7] , that perception – not only visual but by way of other sensory modalities as well – is not an operation, internal to the perceiver, by which the brain adds mental form to the formless raw material of bodily sensation, but rather an ongoing activity of the entire living being, equipped with eyes, ears, nose and so on, in a richly structured environment. It is the being that sees things, not its brain, and it does so not by recognising forms it already knows but by moving around in, and actively exploring, its world. The things it perceives are really there, their features fully specified by invariant properties of the ever-changing stimulus array, such as in the pattern of reflected light, as you move around them. You don’t need to have a preconceived image to know that something is there, and to detect its shape, form and texture, even if you have no idea what it is.

That’s for seeing things in the light. But what of light itself? Obviously, without light we would see nothing. So perhaps, ‘light’ is just another way of saying ‘I can see.'[8] It is the experience of being bathed in illumination. Even the visually impaired, who find it difficult to make out the things around them with any precision, share this experience. As I’ve said before, this not the light that physics would recognize as a species of electromagnetic radiation. It is rather the light of the shining sun and the pale moon, of the twinkling stars, of the lightning flash and the shimmering aurora borealis. We don’t just see these phenomena. We see with them, in the real time of our own visual awareness. They are as much in our own eyes as at large in the cosmos, not because they exist in two places at once, joined by a long straight line of transmission, but because in our experience, the field of visual awareness and the great expanse or the cosmos have merged into one.

Perhaps that’s what you are getting at when you say you that you feel you’re inside a cosmos which is itself a huge brain. To enter your drawings – and you have to enter them, you can’t just stand and look at them – is akin to bearing witness to the explosive birth of this cosmos. But that’s nothing like the ‘big bang’ with which astronomers like to identify the origin of what they call the universe. We have indeed reached a point in this conversation when we can no longer talk about the universe and the cosmos as if they meant the same thing. Let me explain.

According to geographer, orientalist, and philosopher Agustin Berque,[9] the universe of modern astronomy is a cosmos turned inside out, such that the world that was once both around and within us becomes a world without us – objective, exterior and indifferent to our concerns. If the physical universe originated in one big bang, the cosmos is originating all the time, as we are too. It is a process of perpetual birth. It is where our word ‘nature’ comes from – from the Latin natus, to be born.

There is thus a real sense in which with every moment we open our eyes to the world, it is as if for the first time. Whenever sensing meets the sensible, as phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty[10] put it, there is ignited a spark which sets off an explosion of sorts. And I believe that what we witness, in your drawings, is this very explosion, detonated by the fusion of the two worlds of cosmos and affect, or better, perhaps, of dreams and waking life. But the birth of the new is also the fracturing of the old, as the explosion rips through the contorted, fossilized beds of ancient sediments.

Have I come any closer to understanding what drives you in your work? I hope so. And yet, I still have a question for you. You say that you have a mental image in your mind, and that you can keep on returning to it for many days or weeks before you even begin the work of drawing it out on a surface. Yet I wonder how it is possible to prepare such a picture of a world that is never the same from one moment to the next, or that is by its nature explosive?

Writing about plans and situated actions, sociologist Lucy Suchman[11] suggests the example of whitewater kayaking. The kayaker may spend long hours observing the raging river-waters, and rehearsing every move in her head. But once embarked in the rapids, she relies on her own, finely honed skills of acute perception and rapid response, and not on any prior plan, to get her through. I wonder, is it the same for you? Or to rephrase the question: do you plan everything out first, in your head, so that all you have to do, in the drawing, is to transfer the readymade design from a mental surface to a material one? Or are you more like the kayaker, for whom the hours of preparation are meant to fashion an optimal springboard from which to launch into the action? And once launched, do you, like her, compose your movements as you go along?

Abdelkader Benchamma – I read your reply and your text with great interest and great pleasure. Thank you so much for having gone to the effort to draw out these parallels with my work, which today I find beautiful and interesting. I was very pleased with your comparison with Lucy Suchman’s kayaker preparing herself by mentally rehearsing the flow, the movement, and the turbulence of the river the better to anticipate them – all the while not knowing what she’ll find once she’s actually in the water. It’s a lovely metaphor for my drawing and creative practice. When we engage in the act of creation, we are always composed of everything that we have seen, read, loved, and even forgotten.

I read that a part of the brain makes no distinction between a movement which has been mentally visualized and one which has been physically realized. Moreover, many professional athletes train like this: visualizing and mentally replaying moves and sequences of movements so that they can execute them spontaneously. They create familiarity through their powers of imagination. This idea of tricking the brain is interesting. On this subject, Bruce Lee warned against making disparaging references to oneself, even in jest; the brain wouldn’t be able to recognize the distinction. I think, all the same, that being able to laugh about oneself is necessary.

I’m in the countryside; I’ve been able to read but it’s been more than a week since I’ve drawn anything. The beginning of the year has been very intense thanks to my realizing two drawing installations one after the other. This doesn’t happen often as I find it essential to leave long periods between one project and the next. This time, however, it was wonderful and interesting to get caught up in the flow, in a dynamic, in a looser, freer, kind of drawing. I would say that this time my drawing style corresponded well with the forces depicted on the walls.

To be completely honest, I’ve been deeply depressed and completely hollowed out by the living nightmare currently playing out in Gaza, which isn’t really a war. I didn’t want to do anything anymore: I no longer had any energy to draw or write. Suddenly you ask yourself why you bother creating. What good can it do in the face of such inhumanity? There are periods where you can almost feel a kind of subsidence, a collapse of everything that makes us human. Perhaps in the end all this civilization around us is little more than a thin veneer which could shatter in an instant. And just as anguishing is our faculty for accepting it all. Carl Gustav Jung spoke of periods during the rise of Nazism where many of his patients experienced very similar nightmares. Perhaps we are far more connected to each other and to certain things without our knowing it.

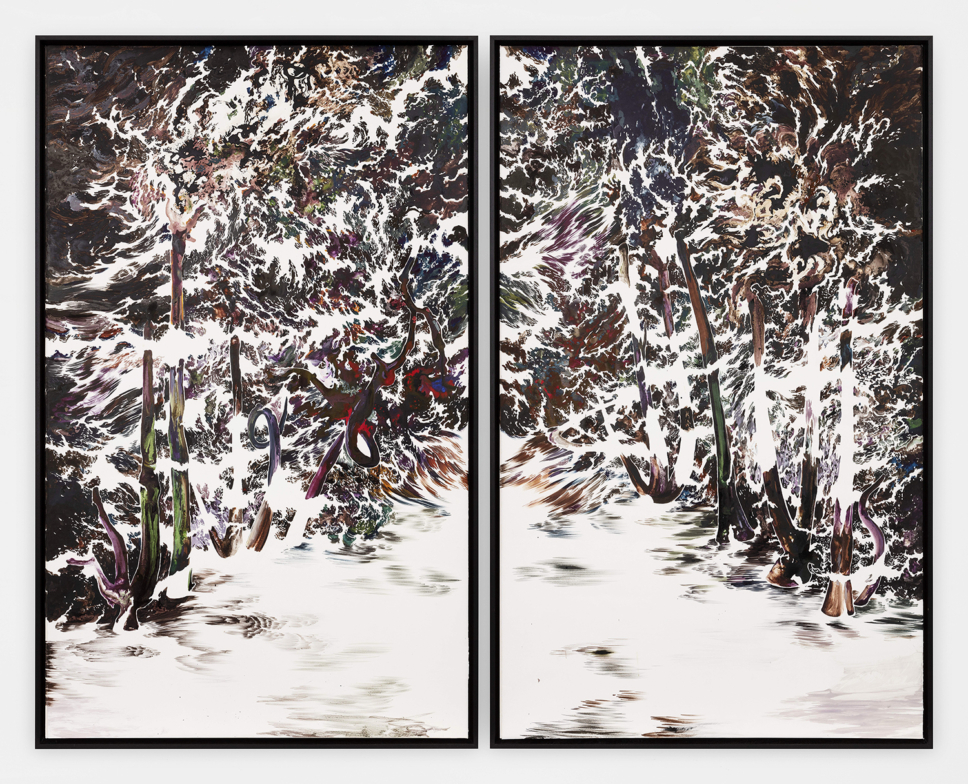

So, in order to escape from this darkness, I have begun to draw trees, without asking myself why, really as a prayer. These trees were, as it happens, inspired by prayers from the Qu’ran, almost calligraphy. A little each day like a promise for a little humanity to come.

Tim Ingold – Let us give the last word then to the trees!

—

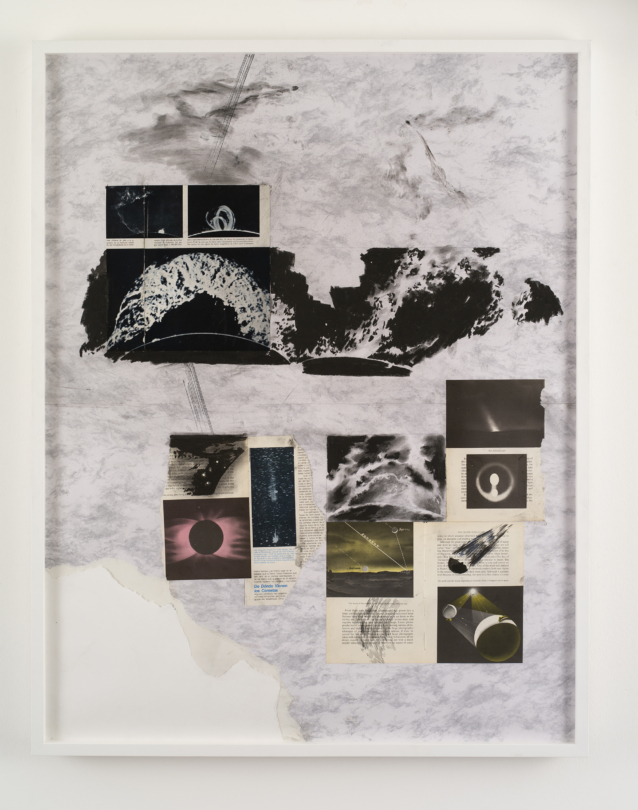

Header: Exhibition view “Solastalgia: Archaeologies of Loss”, October 13, 2023 – March 24, 2024, The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada

2nd image: L’horizon des événements, 2019, detail.Ink on paper mounted on canvas, triptych, 98 3/8 × 59 in each.

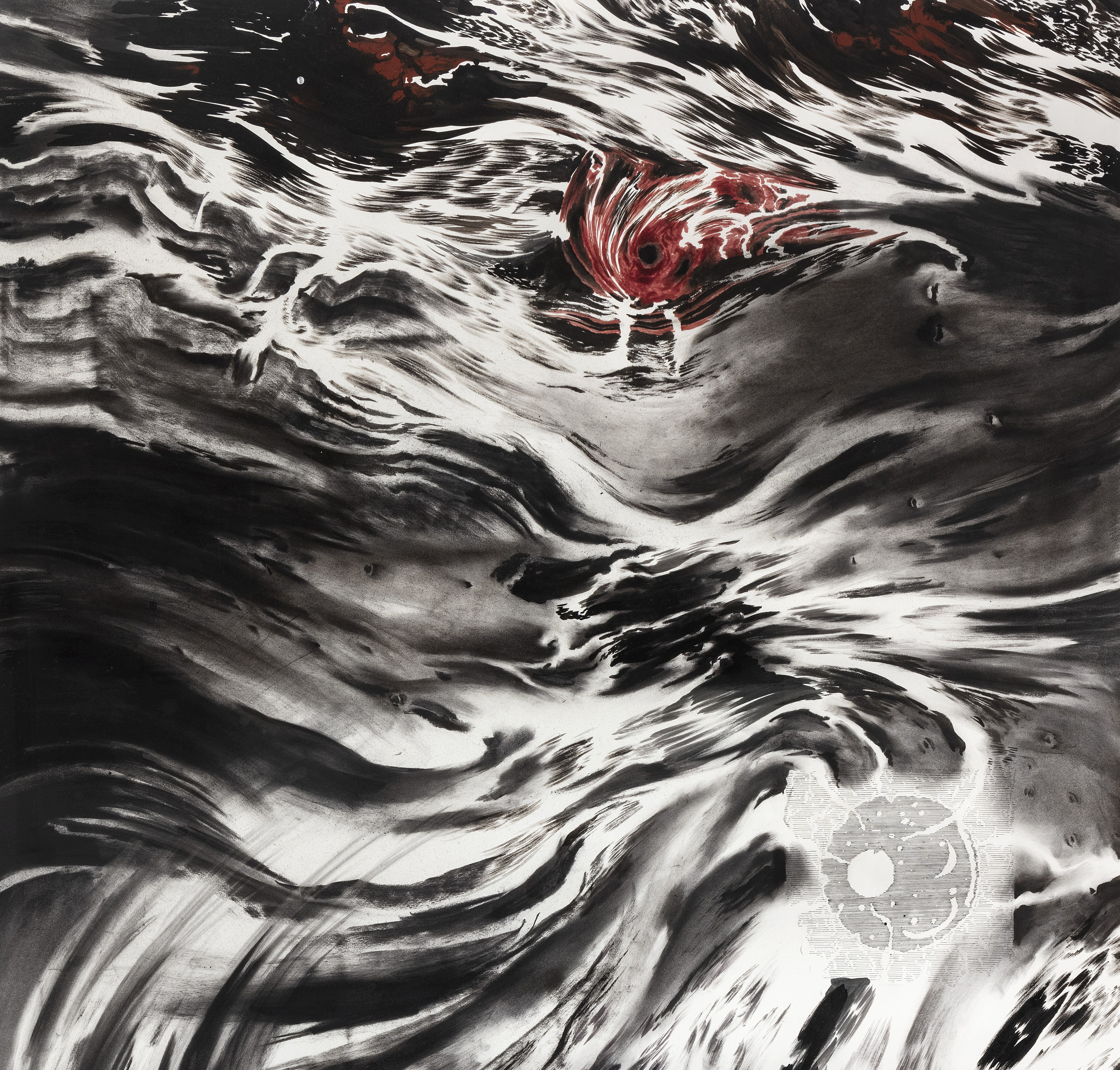

Last image: White Dwarf, 2023, detail. Ink and charcoal on paper, 63 × 45 1/4 in.

[1] William James, Psychology, New York: Henry Holt, 1892, p.14.

[2] Tim Ingold, Correspondences, Cambridge: Polity, 2020, pp.30-31.

[3] Paul Klee, Notebooks, Volume 1: The Thinking Eye, translated by Ralph Manheim. London: Lund Humphries, 1973, pp.112-13.

[4] Georges Didi-Hubermann, Phasmes : Essais sur l’apparition, tome I, Paris : Minuit, 1998.

[5] Don Dellilo. Cosmopolis, New York: Scribner, 2003.

[6] Clélie Millner, « Heuristique et scepticisme dans Notturno indiano d’Antonio Tabucchi », Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2007. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/trans/194

[7] James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

[8] Tim Ingold, The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill, Londres, Routledge, 2000, p.265.

[9] Agustin Berque, Thinking Through Landscape, translated by Anne-Marie Feenberg-Dibon, London: Routledge, 2013, p.51.

[10] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception, and Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics, Evanston, IL, Northwestern University Press, 1964, p.163.

[11] Lucy Suchman, Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987, p.52.

Arbres – Mondes Souterrains

Tim Ingold is Professor Emeritus of Social Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen. He has carried out fieldwork among Saami and Finnish people in Lapland, and has written on environment, technology, and social organisation in the circumpolar North, on animals in human society, and on human ecology and evolutionary theory. His more recent work explores environmental perception and skilled practice. Ingold’s current interests lie on the interface between anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. His recent books include The Perception of the Environment (2000), Lines (2007), Being Alive (2011), Making (2013), The Life of Lines (2015), Anthropology and/as Education (2018), Anthropology: Why it Matters (2018), Correspondences (2020), Imagining for Real (2022) and The Rise and Fall of Generation Now (2023). Ingold is a Fellow of the British Academy and the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 2022 he was made a CBE for services to Anthropology.

Né en 1975 à Mazamet (France), Abdelkader Benchamma vit et travaille à Paris et Montpellier. Benchamma a choisi le dessin noir et blanc comme medium de prédilection. Variant les approches graphiques, il aborde tantôt la feuille d’un trait minutieux de graveur tantôt le mur d’un geste généreux qui s’approprie l’espace. La matière s’évade du cadre dans une croissance organique. Nourris de littérature, de philosophie, d’astrophysique, de réflexions ésotériques, ses environnements mettent en œuvre des scénarios visuels qui questionnent notre rapport au réel sondant les frontières avec l’invisible.